Difference between revisions of "Reports du Tres Erudite Edmund Saunders"

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

|set=2 volumes in 1 | |set=2 volumes in 1 | ||

|desc=Folio (32 cm.) | |desc=Folio (32 cm.) | ||

| − | }}Sir Edmund Saunders (d. 1683), judge and law reporter, was born | + | }}Sir Edmund Saunders (d. 1683), judge and law reporter, was born near Gloucester of humble beginnings, but his alacrity of mind quickly elevated him to a position of prominence within the legal profession.<ref>Stuart Handley, [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/24691?docPos=1 “Saunders, Sir Edmund (d. 1683)”], ‘’Oxford Dictionary of National Biography’’ (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed February 21, 2014.</ref> He started out “courting the attorney’s clerks” for work at Clements Inn.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Due to his proficiency, the clerks placed him in a more permanent position as their copyist, which enabled him to eventually become an “exquisite entering clerk.”<ref>Ibid.</ref> His work did not go unnoticed; he entered Middle Temple in 1660 and was called to bar in 1664.<ref>Ibid.</ref> |

| − | + | Saunders began writing his reports in 1666 and continued to do so until 1672.<ref>Ibid.</ref> They reflect the quickness with which he established a very large practice; in 1680 he was the leading pleader on the pleas side and the fifth for the crown.<ref>Ibid.</ref> He argued many high profile cases, including those of several individuals involved in the Popish Plot.<ref>Ibid.</ref> In 1682, Saunders was made a king’s counsel to Charles II, and he became a bencher in the Middle Temple later that year.<ref>Ibid.</ref> | |

| − | A sickly man, Saunders died in 1683 of the “palsy, stone, and a complication of other distempers.”<ref>Ibid.</ref> | + | A sickly man, Saunders died in 1683 of the “palsy, stone, and a complication of other distempers.”<ref>Ibid.</ref> He had never married and had no children, and willed his estate to Nathaniel Earle and his wife, with whom he had lived for many years.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Saunders never had a high regard for fees during his lifetime and left a significant amount of money for the poor.<ref>Ibid.</ref> |

| − | To say that Saunders’ reports are excellent is an understatement; brilliant is a more apt description. Scholars consider his works “the most valuable and accurate reports of their age,” worthy of “the homage of the world.”<ref>John William Wallace, “The Reporters Arranged and Characterized with Incidental Remarks'' (Boston: Soule and Bugbee, 1882) 338.</ref> Their value has not been limited to English common law. The famous | + | To say that Saunders’ reports are excellent is an understatement; brilliant is a more apt description. Scholars consider his works “the most valuable and accurate reports of their age,” worthy of “the homage of the world.”<ref>John William Wallace, “The Reporters Arranged and Characterized with Incidental Remarks'' (Boston: Soule and Bugbee, 1882) 338.</ref> Their value has not been limited to English common law. The famous American orator Daniel Webster, who learned “legal logic” from the reports, found them to be of such great importance that he translated them into English.<ref>Ibid.</ref> |

| − | + | The reports are “frank and simple” in their design,<ref>J. G. Marvin, ''Legal Bibliography or a Thesaurus of American, English, Irish, and Scotch Law Books'' (Philadelphia: T. & J. W. Johnson, Law Booksellers, 1847),630.</ref> and unlike other early reports, contain few errors.<ref>Percy H. Winfield, ''The Chief Sources of English Legal History'' (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1925),284.</ref> The substantive material reflects the author’s abilities as the preeminent pleader of his day and it derives much of its value from his expertise.<ref>J.G. Marvin, ‘’Legal Bibliography,’’ 630.</ref> Well into the nineteenth century, Saunders’ works remained the “Bible of the Law of Special Pleading.”<ref>Ibid.</ref> | |

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

Revision as of 10:32, 16 March 2014

by Sir Edmund Saunders

| Saunders' Reports | |

|

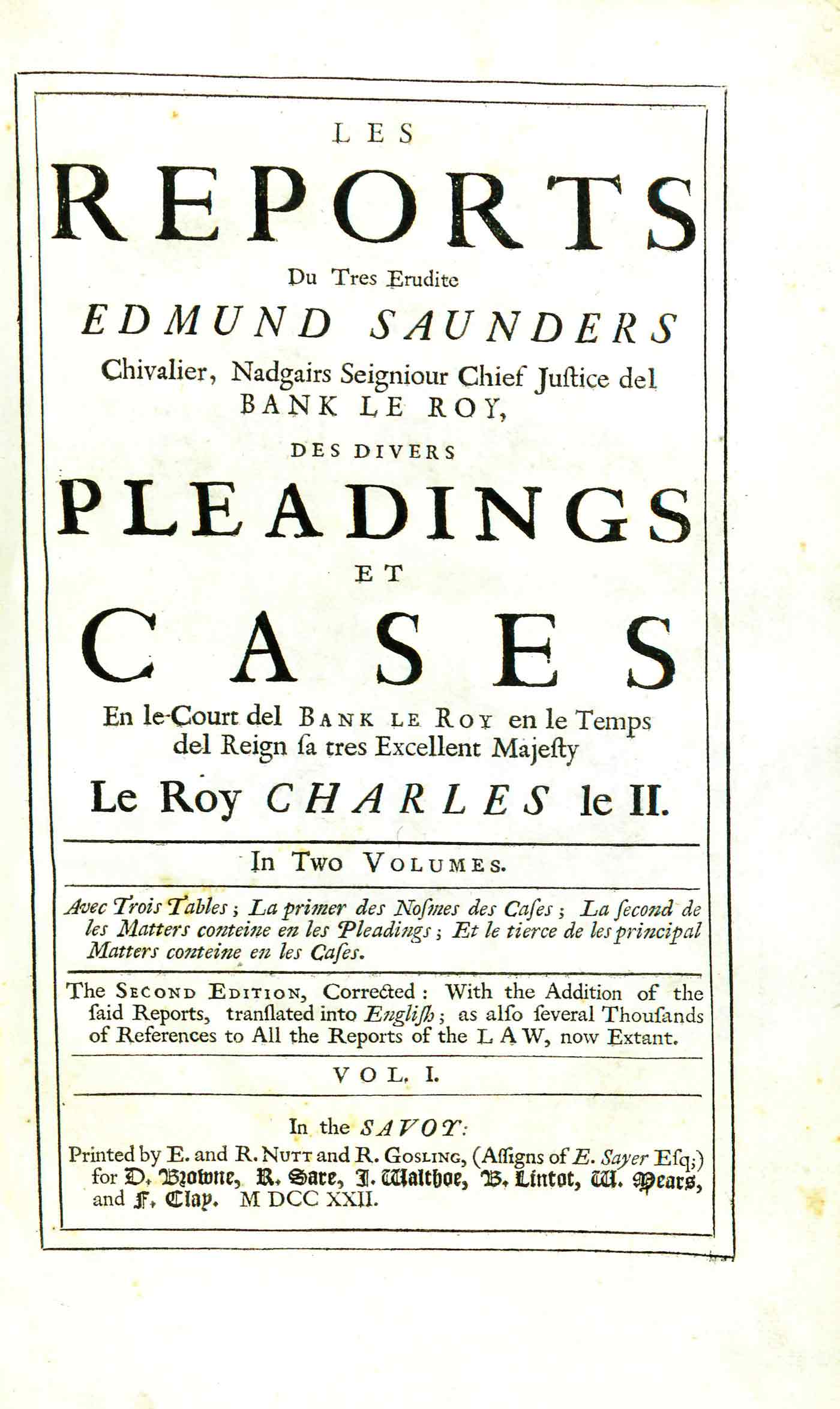

Title page from Les Reports du Tres Erudite Edmund Saunders, volume one, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Sir Edmund Saunders |

| Published | [London] In the Savoy: D. Browne |

| Date | 1722 |

| Edition | Second, corrected |

| Language | French |

| Volumes | 2 volumes in 1 volume set |

| Desc. | Folio (32 cm.) |

Sir Edmund Saunders (d. 1683), judge and law reporter, was born near Gloucester of humble beginnings, but his alacrity of mind quickly elevated him to a position of prominence within the legal profession.[1] He started out “courting the attorney’s clerks” for work at Clements Inn.[2] Due to his proficiency, the clerks placed him in a more permanent position as their copyist, which enabled him to eventually become an “exquisite entering clerk.”[3] His work did not go unnoticed; he entered Middle Temple in 1660 and was called to bar in 1664.[4]

Saunders began writing his reports in 1666 and continued to do so until 1672.[5] They reflect the quickness with which he established a very large practice; in 1680 he was the leading pleader on the pleas side and the fifth for the crown.[6] He argued many high profile cases, including those of several individuals involved in the Popish Plot.[7] In 1682, Saunders was made a king’s counsel to Charles II, and he became a bencher in the Middle Temple later that year.[8]

A sickly man, Saunders died in 1683 of the “palsy, stone, and a complication of other distempers.”[9] He had never married and had no children, and willed his estate to Nathaniel Earle and his wife, with whom he had lived for many years.[10] Saunders never had a high regard for fees during his lifetime and left a significant amount of money for the poor.[11]

To say that Saunders’ reports are excellent is an understatement; brilliant is a more apt description. Scholars consider his works “the most valuable and accurate reports of their age,” worthy of “the homage of the world.”[12] Their value has not been limited to English common law. The famous American orator Daniel Webster, who learned “legal logic” from the reports, found them to be of such great importance that he translated them into English.[13]

The reports are “frank and simple” in their design,[14] and unlike other early reports, contain few errors.[15] The substantive material reflects the author’s abilities as the preeminent pleader of his day and it derives much of its value from his expertise.[16] Well into the nineteenth century, Saunders’ works remained the “Bible of the Law of Special Pleading.”[17]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Both Dean's Memo[18] and Brown's Bibliography[19] list the second edition (1722) of this title based on entries in John Marshall's law notes.[20] The Wolf Law Library purchased a copy of the same edition.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Rebound in period style quarter-calf with marbled boards. View this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

References

- ↑ Stuart Handley, “Saunders, Sir Edmund (d. 1683)”, ‘’Oxford Dictionary of National Biography’’ (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed February 21, 2014.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ John William Wallace, “The Reporters Arranged and Characterized with Incidental Remarks (Boston: Soule and Bugbee, 1882) 338.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ J. G. Marvin, Legal Bibliography or a Thesaurus of American, English, Irish, and Scotch Law Books (Philadelphia: T. & J. W. Johnson, Law Booksellers, 1847),630.

- ↑ Percy H. Winfield, The Chief Sources of English Legal History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1925),284.

- ↑ J.G. Marvin, ‘’Legal Bibliography,’’ 630.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Memorandum from Barbara C. Dean, Colonial Williamsburg Found., to Mrs. Stiverson, Colonial Williamsburg Found. (June 16, 1975), 7 (on file at Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary).

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

- ↑ The Papers of John Marshall, eds. Herbert A. Johnson, Charles T. Cullen, and Nancy G. Harris (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, in association with the Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1974), 1:57.