Difference between revisions of "Publii Ovidii Nasonis Metamorphoseon Libri XV"

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

|pages=[8], 475, [173] | |pages=[8], 475, [173] | ||

|desc=8vo (21 cm.) | |desc=8vo (21 cm.) | ||

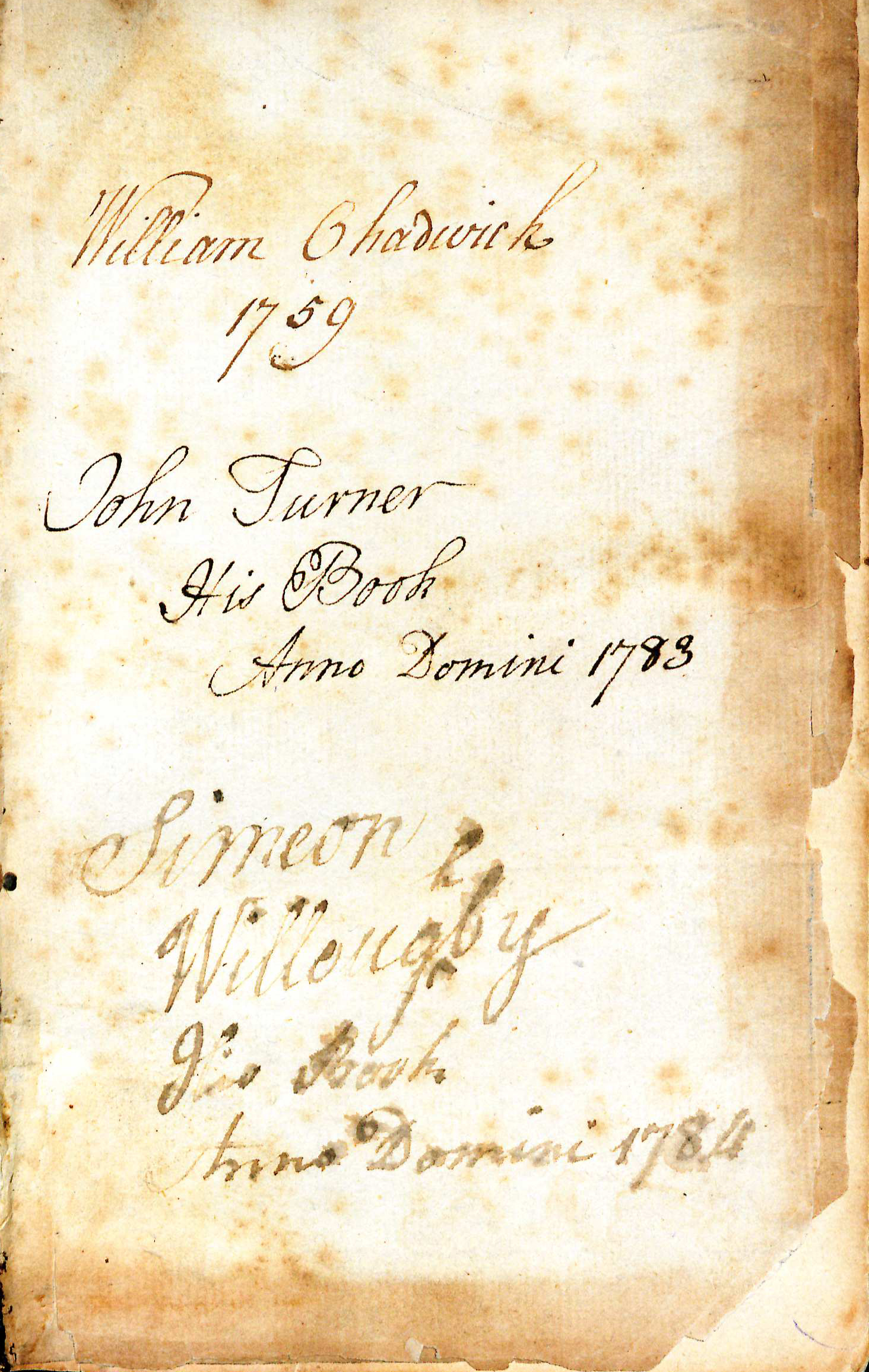

| − | }}[[File:OvidMetamorphoseon1751Inscriptions.jpg|left|thumb|250px|<center>Inscriptions, front free endpaper.</center>]]Modern readers are fortunate that the Roman elegiac poet [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ovid Ovid] (Publius Ovidius Naso) wrote of his own life in one of his poems, ''Tristia''.<ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-2187 "Ovid”] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'', ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> He received a Roman education due to his family’s high social and political status as equestrians.<ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192801463.001.0001/acref-9780192801463-e-1578 "Ovid"] in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World'', ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).</ref> As the culmination of his studies, Ovid went on the typical aristocratic “Grand Tour” of Greece.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Political life was not for him, so after Ovid held minor posts in Rome, he dedicated his life to poetry and became part of Messallian group of poets.<ref>"Ovid” in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature.''</ref> By 8 CE, Ovid “was the leading poet of Rome” but was suddenly banished by the Emperor Augustus to the city Tomis due to a poem and an error which offended the emperor.<ref>"Ovid" in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World''.</ref> During this ten-year Ovid kept his Roman property and civic rights, but his books were removed from public libraries in Rome.<ref>"Ovid” in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature''.</ref><br/> | + | }}[[File:OvidMetamorphoseon1751Inscriptions.jpg|left|thumb|250px|<center>Inscriptions, front free endpaper.</center>]]Modern readers are fortunate that the Roman elegiac poet [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ovid Ovid] (Publius Ovidius Naso) wrote of his own life in one of his poems, ''Tristia''.<ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-2187 "Ovid”] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'', ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> He received a Roman education due to his family’s high social and political status as equestrians.<ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192801463.001.0001/acref-9780192801463-e-1578 "Ovid"] in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World'', ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).</ref> As the culmination of his studies, Ovid went on the typical aristocratic “Grand Tour” of Greece.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Political life was not for him, so after Ovid held minor posts in Rome, he dedicated his life to poetry and became part of Messallian group of poets.<ref>"Ovid” in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature.''</ref> By 8 CE, Ovid “was the leading poet of Rome” but was suddenly banished by the Emperor Augustus to the city Tomis due to a poem and an error which offended the emperor.<ref>"Ovid" in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World''.</ref> During this ten-year ban, Ovid kept his Roman property and civic rights, but his books were removed from public libraries in Rome.<ref>"Ovid” in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature''.</ref><br/> |

<br/> | <br/> | ||

''Metamorphoses'' contains a wide variety of memorable myths and legends, each telling of some type of supernatural transformation, “call[ing] attention to the boundaries between divine and human, animal and inanimate, raising fundamental questions about definition and hierarchy in the universe.”<ref>"Ovid" in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World''.</ref> Ovid’s mastery of elegiac poetry was unsurpassed. “No Roman poet can equal Ovid’s impact upon western art and culture. Esp[ecially] remarkable in its appropriations has been the Metamorphoses.”<ref>Ibid.</ref> | ''Metamorphoses'' contains a wide variety of memorable myths and legends, each telling of some type of supernatural transformation, “call[ing] attention to the boundaries between divine and human, animal and inanimate, raising fundamental questions about definition and hierarchy in the universe.”<ref>"Ovid" in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World''.</ref> Ovid’s mastery of elegiac poetry was unsurpassed. “No Roman poet can equal Ovid’s impact upon western art and culture. Esp[ecially] remarkable in its appropriations has been the Metamorphoses.”<ref>Ibid.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 15:08, 14 March 2014

by Ovid

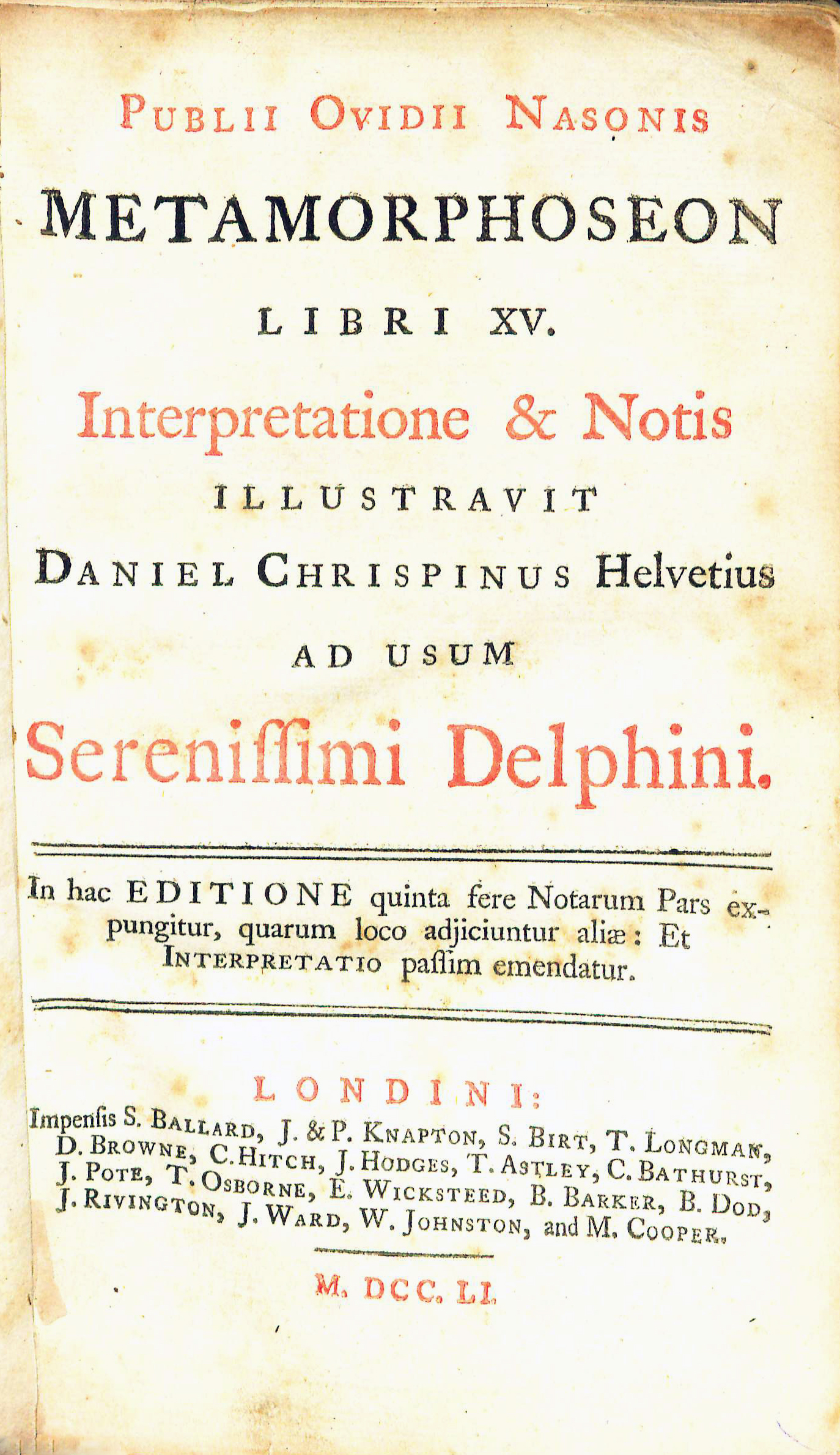

| Publii Ovidii Nasonis Metamorphoseon Libri XV | |

|

Title page from Publii Ovidii Nasonis Metamorphoseon Libri XV, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Ovid |

| Editor | Daniel Crispin |

| Published | Londini: Impensis S. Ballard, J. & P. Knapton, S. Birt, T. Longman, D. Browne [and 13 others in London] |

| Date | 1751 |

| Edition | In hac editione quinta fere notarum pars expungitur |

| Language | Latin |

| Pages | [8], 475, [173] |

| Desc. | 8vo (21 cm.) |

Metamorphoses contains a wide variety of memorable myths and legends, each telling of some type of supernatural transformation, “call[ing] attention to the boundaries between divine and human, animal and inanimate, raising fundamental questions about definition and hierarchy in the universe.”[7] Ovid’s mastery of elegiac poetry was unsurpassed. “No Roman poet can equal Ovid’s impact upon western art and culture. Esp[ecially] remarkable in its appropriations has been the Metamorphoses.”[8]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as "Ovidii Metamorphoseon. Delph. 8vo." This was one of the books kept by Thomas Jefferson. He sold a copy to the Library of Congress in 1815, but it no longer exists to verify the edition or Wythe's prior ownership.[9] George Wythe's Library[10] on LibraryThing merely indicates "Precise edition unknown." The Brown Bibliography[11] includes the 1751 edition based on E. Millicent Sowerby's inclusion of that edition in Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson. The Wolf Law Library purchased a copy of the same edition.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in original calf with gilt compartments to spine. Includes previous owner inscriptions "William Chadwick, 1759," "John Turner, His Book, Anno Domini 1783," and "Simeon Willoughby, His Book, Anno Domini 1784" on the front free endpaper. Purchased from Tony Hutchinson.

References

- ↑ "Ovid” in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- ↑ "Ovid" in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World, ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ "Ovid” in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature.

- ↑ "Ovid" in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World.

- ↑ "Ovid” in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature.

- ↑ "Ovid" in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ E. Millicent Sowerby, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson 2nd ed. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983), 4:449 (no.4339).

- ↑ LibraryThing, s. v. "Member: George Wythe", accessed February 28, 2014.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

External Links

Read this book in Google Books.