Difference between revisions of "Oceana of James Harrington"

(Summary paragraph by Melissa Fussell and Evidence.) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE:''The Oceana of James Harrington, and His Other Works''}} | {{DISPLAYTITLE:''The Oceana of James Harrington, and His Other Works''}} | ||

| + | <big>The Oceana of James Harrington, and his Other Works: Som [sic] Wherof are now First Publish'd from His Own Manuscripts</big> | ||

===by James Harrington=== | ===by James Harrington=== | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

| − | + | {{BookPageInfoBox | |

| − | [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Harrington_%28author%29 James Harrington] (1611-1677) was a political theorist in the seventeenth century. Although he left Trinity College in Oxford without a degree, Harrington was an accomplished private scholar.<ref>H. M. Höpfl, [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/12375 "Harrington, James (1611–1677)" in ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed October 11, 2013.</ref> The ''Oceana'' text could be fairly called the defining work of Harrington’s career.<ref>Ibid.</ref> ''Commonwealth of Oceana'', written in 1656, presented an image of an idealized world in which the British gentry social class had absolute power.<ref>''The Columbia Encyclopedia'', s.v. "Harrington, James," (Columbia University Press, 2013-), accessed October 11, 2013, http://www.credoreference.com/entry/columency/harrington_james.</ref> Harrington’s portrayal was powerful. He notably attacked Hobbes in ''Oceana'' for what Harrington saw as an ineffective distinction between authority and power.<ref>Höpfl, "Harrington, James."</ref> Harrington was a wealthy man, with much to gain from social connections, but still argued fervently for what he called a return to “ancient prudence.”<ref>Ibid.</ref> Harrington meant by this that the government should not be composed of men, but of legal doctrines and rules.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Although it may seem counter-intuitive to those not familiar with his work, Harrington was actually an agrarian who advocated for a more equal distribution of power.<ref>Ibid.</ref> In fact, it has been argued that William Penn’s government in Pennsylvania was influenced by ''Oceana''.<ref>''The Columbia Encyclopedia'', s.v. "Harrington, James,"</ref> Harrington's theories on equality were also reflected in both the American and French revolutions.<ref>Ibid.</ref><br /> | + | |imagename=HarringtonOceana1700.jpg |

| + | |link=https://catalog.swem.wm.edu/law/Record/2080652 | ||

| + | |shorttitle=The Oceana of James Harrington | ||

| + | |author=James Harrington | ||

| + | |publoc=London | ||

| + | |publisher=Printed [by J. Darby?] and are to be sold by the booksellers of London and Westminster | ||

| + | |year=1700 | ||

| + | |edition=First | ||

| + | |lang=English | ||

| + | |pages=xliv, 546 p. | ||

| + | |desc=(32 cm.) | ||

| + | }}[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Harrington_%28author%29 James Harrington] (1611-1677) was a political theorist in the seventeenth century. Although he left Trinity College in Oxford without a degree, Harrington was an accomplished private scholar.<ref>H. M. Höpfl, [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/12375 "Harrington, James (1611–1677)" in ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed October 11, 2013.</ref> The ''Oceana'' text could be fairly called the defining work of Harrington’s career.<ref>Ibid.</ref> ''Commonwealth of Oceana'', written in 1656, presented an image of an idealized world in which the British gentry social class had absolute power.<ref>''The Columbia Encyclopedia'', s.v. "Harrington, James," (Columbia University Press, 2013-), accessed October 11, 2013, http://www.credoreference.com/entry/columency/harrington_james.</ref> Harrington’s portrayal was powerful. He notably attacked Hobbes in ''Oceana'' for what Harrington saw as an ineffective distinction between authority and power.<ref>Höpfl, "Harrington, James."</ref> Harrington was a wealthy man, with much to gain from social connections, but still argued fervently for what he called a return to “ancient prudence.”<ref>Ibid.</ref> Harrington meant by this that the government should not be composed of men, but of legal doctrines and rules.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Although it may seem counter-intuitive to those not familiar with his work, Harrington was actually an agrarian who advocated for a more equal distribution of power.<ref>Ibid.</ref> In fact, it has been argued that William Penn’s government in Pennsylvania was influenced by ''Oceana''.<ref>''The Columbia Encyclopedia'', s.v. "Harrington, James,"</ref> Harrington's theories on equality were also reflected in both the American and French revolutions.<ref>Ibid.</ref><br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

''The Oceana of James Harrington, and His Other Works'', first edited as a collection in 1700 by John Toland, includes ''The Grounds and Reasons of Monarchy Consider'd'', ''The Commonwealth of Oceana'', ''The Prerogative of Popular Government'', ''The Art of Lawgiving'', and "Six political tracts written on several occasions," as well as Toland's "The Life of James Harrington." | ''The Oceana of James Harrington, and His Other Works'', first edited as a collection in 1700 by John Toland, includes ''The Grounds and Reasons of Monarchy Consider'd'', ''The Commonwealth of Oceana'', ''The Prerogative of Popular Government'', ''The Art of Lawgiving'', and "Six political tracts written on several occasions," as well as Toland's "The Life of James Harrington." | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

Revision as of 15:44, 4 February 2014

The Oceana of James Harrington, and his Other Works: Som [sic] Wherof are now First Publish'd from His Own Manuscripts

by James Harrington

| The Oceana of James Harrington | |

|

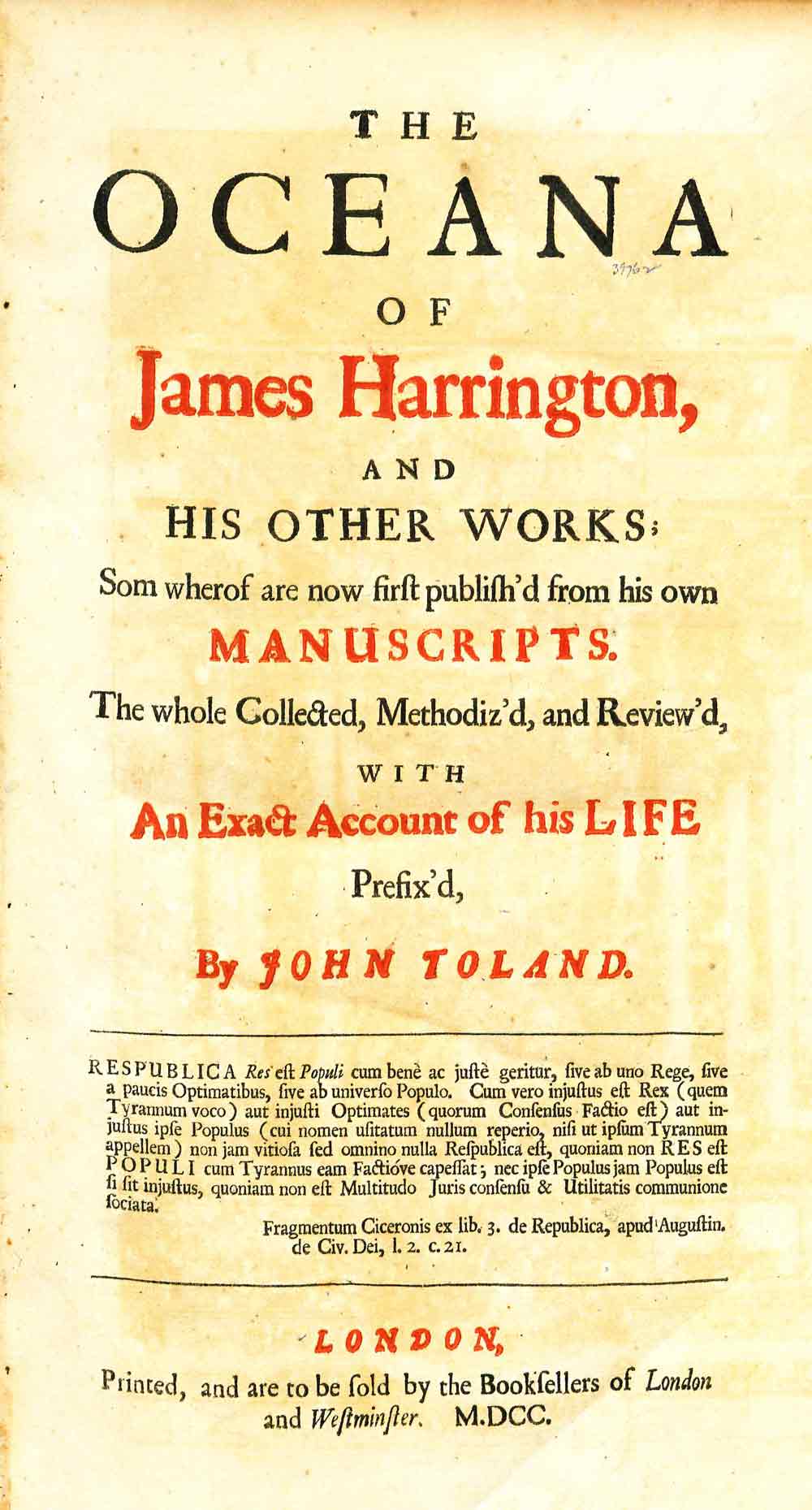

Title page from The Oceana of James Harrington, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | James Harrington |

| Published | London: Printed [by J. Darby?] and are to be sold by the booksellers of London and Westminster |

| Date | 1700 |

| Edition | First |

| Language | English |

| Pages | xliv, 546 p. |

| Desc. | (32 cm.) |

James Harrington (1611-1677) was a political theorist in the seventeenth century. Although he left Trinity College in Oxford without a degree, Harrington was an accomplished private scholar.[1] The Oceana text could be fairly called the defining work of Harrington’s career.[2] Commonwealth of Oceana, written in 1656, presented an image of an idealized world in which the British gentry social class had absolute power.[3] Harrington’s portrayal was powerful. He notably attacked Hobbes in Oceana for what Harrington saw as an ineffective distinction between authority and power.[4] Harrington was a wealthy man, with much to gain from social connections, but still argued fervently for what he called a return to “ancient prudence.”[5] Harrington meant by this that the government should not be composed of men, but of legal doctrines and rules.[6] Although it may seem counter-intuitive to those not familiar with his work, Harrington was actually an agrarian who advocated for a more equal distribution of power.[7] In fact, it has been argued that William Penn’s government in Pennsylvania was influenced by Oceana.[8] Harrington's theories on equality were also reflected in both the American and French revolutions.[9]

The Oceana of James Harrington, and His Other Works, first edited as a collection in 1700 by John Toland, includes The Grounds and Reasons of Monarchy Consider'd, The Commonwealth of Oceana, The Prerogative of Popular Government, The Art of Lawgiving, and "Six political tracts written on several occasions," as well as Toland's "The Life of James Harrington."

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

A version of Harrington's Oceana is included in both Dean's Memo[10] and Brown's Bibliography[11] based on a reference in William Clarkin's biography of Wythe. In discussing Thomas Jefferson's education under Wythe, Clarkin states "[w]e do know that Jefferson studied ... Harrington's Oceana" but Clarkin provides no source of corroborating evidence.[12] Brown suggests the first edition, Commonwealth of Oceana based on the copy Jefferson sold to the Library of Congress.[13] The Wolf Law Library purchased the first edition of collected works, The Oceana of James Harrington, and his Other Works following Dean's memo, the original source for the George Wythe Collection.

View this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

External Links

References

- ↑ H. M. Höpfl, [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/12375 "Harrington, James (1611–1677)" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed October 11, 2013.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ The Columbia Encyclopedia, s.v. "Harrington, James," (Columbia University Press, 2013-), accessed October 11, 2013, http://www.credoreference.com/entry/columency/harrington_james.

- ↑ Höpfl, "Harrington, James."

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ The Columbia Encyclopedia, s.v. "Harrington, James,"

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Memorandum from Barbara C. Dean, Colonial Williamsburg Found., to Mrs. Stiverson, Colonial Williamsburg Found. (June 16, 1975), 11 (on file at Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary).

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

- ↑ William Clarkin, Serene Patriot: A Life of George Wythe (Albany, New York: Alan Publications, 1970), 42.

- ↑ E. Millicent Sowerby, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, 2nd ed. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983), 3:15 [no.2335].