Difference between revisions of "Paradise Regain'd"

Mvanwicklin (talk | contribs) m |

m (→by John Milton) |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

|desc=[[:Category:Octavos|8vo]] (24 cm.) | |desc=[[:Category:Octavos|8vo]] (24 cm.) | ||

|shelf=M-3 | |shelf=M-3 | ||

| − | }} | + | }}[[wikipedia: John Milton| John Milton]] (1608-1674), was an English poet and polemicist, and a civil servant under [[wikipedia: Oliver Cromwell| Oliver Cromwell]]. Best known for his canonical epic poem, ''Paradise Lost'', Milton began to write poetry in English and Latin at Cambridge in 1625.<ref>Gordon Campbell, [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/18800 "Milton, John (1608–1674),"] ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford University Press, 2004), accessed September 26, 2013. All biographical information is from this source unless otherwise noted.</ref> From this early poetry one can see Milton's critical view of Catholicism. His first published poem was a commendatory poem in the second published folio of Shakespeare’s work in 1632, titled "On Shakespeare."<ref>W.P. Trent, "John Milton," ''The Sewanee Review'', 5, No. 1 (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1897), pp. 2-3.</ref> |

| − | Greatly affected by the deaths of his mother and his friend and fellow poet [ | + | Greatly affected by the deaths of his mother and his friend and fellow poet [[wikipedia:Edward King (British poet)| Edward King]], Milton traveled abroad to Paris and throughout Italy in 1638.<ref>Pauline Lacy Smith, "John Milton as an Educator," ''Peabody Journal of Education'', 23, no. 3 (Taylor & Francis, Ltd., Nov. 1945), pp. 170-71.</ref> When he returned to England, Milton published five anti-prelatical pamphlets that criticize the governance of the Church. With the dissolution of his first marriage in 1642 he began to write extensively on divorce, saying that the breakdown of a marriage should constitute grounds for divorce.<ref>Trent, pp. 8-9.</ref> |

| − | + | Milton's career from 1641-1674 fluctuated between a focus on poetry, political and religious criticisms, and histories. Milton's political writings from 1649-1655 are marked by a disbelief in the divine right of kings, advocacy for a more republican government, and his controversial defense of regicide that made him infamous across Europe. He also wrote a formidable proposal for the reformation of the English education system<ref> Smith, p. 173.</ref>, treatises on the importance of a free press, and a treatise against the use of tithes. After becoming blind in 1652, Milton began to dictate his writing.<ref>W.H. Wilmer, "The Blindness of Milton," ''The Journal of English and Germanic Philology'', 32, no. 3 (University of Illinois Press, Jul. 1993,) p. 308.</ref> | |

| − | + | Milton's political writing in the 1650s controversially challenged monarchy as the best form of government. Instead, he advocated for a republic comprised of a "Grand or Supreme Council" of virtuous aristocrats. This political philosophy of "republican exclusivism" greatly influenced the United States' founding fathers, including [[Thomas Jefferson]].<ref>Nathan R. Perl-Rosenthal, "The 'Divine Right of Republics': Hebraic Republicanism and the Debate over Kingless Government in Revolutionary America," ''The William and Mary Quarterly'', Third Series, 66, No. 3 (Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Jul. 2009), p. 538.</ref> Jefferson specifically used Milton’s ideas that criticized the governance of the church to argue for the separation of church and state in Virginia. | |

| − | Milton's books were ordered to be burned and he was imprisoned in the Tower after the restoration of [ | + | Milton's books were ordered to be burned and he was imprisoned in the Tower after the restoration of [[wikipedia:Charles II of England|Charles II]]. Milton dictated ''Paradise Lost'' from around 1658-1663. This epic poem presents the story of Genesis, with shockingly humanized depictions of God, Satan, Adam and Eve. |

| − | Published in 1671 as something of a sequel to ''Paradise Lost'', ''Paradise Regained'' depicts the | + | Published in 1671 as something of a sequel to ''Paradise Lost'', ''Paradise Regained'' depicts the "temptations of Jesus in the desert" in an unsentimental way. ''Samson Agonistes'' was published along with this work, but it is unclear when Milton wrote this drama. ''Samson Agonistes'' is a play modeled after Greek dramas with clear autobiographical undertones<ref> Smith, p. 172.</ref>, and a modern characterization of Samson as a man struggling to find divine influences in his life. |

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

Revision as of 12:57, 16 September 2019

by John Milton

| Paradise Regain'd | |

|

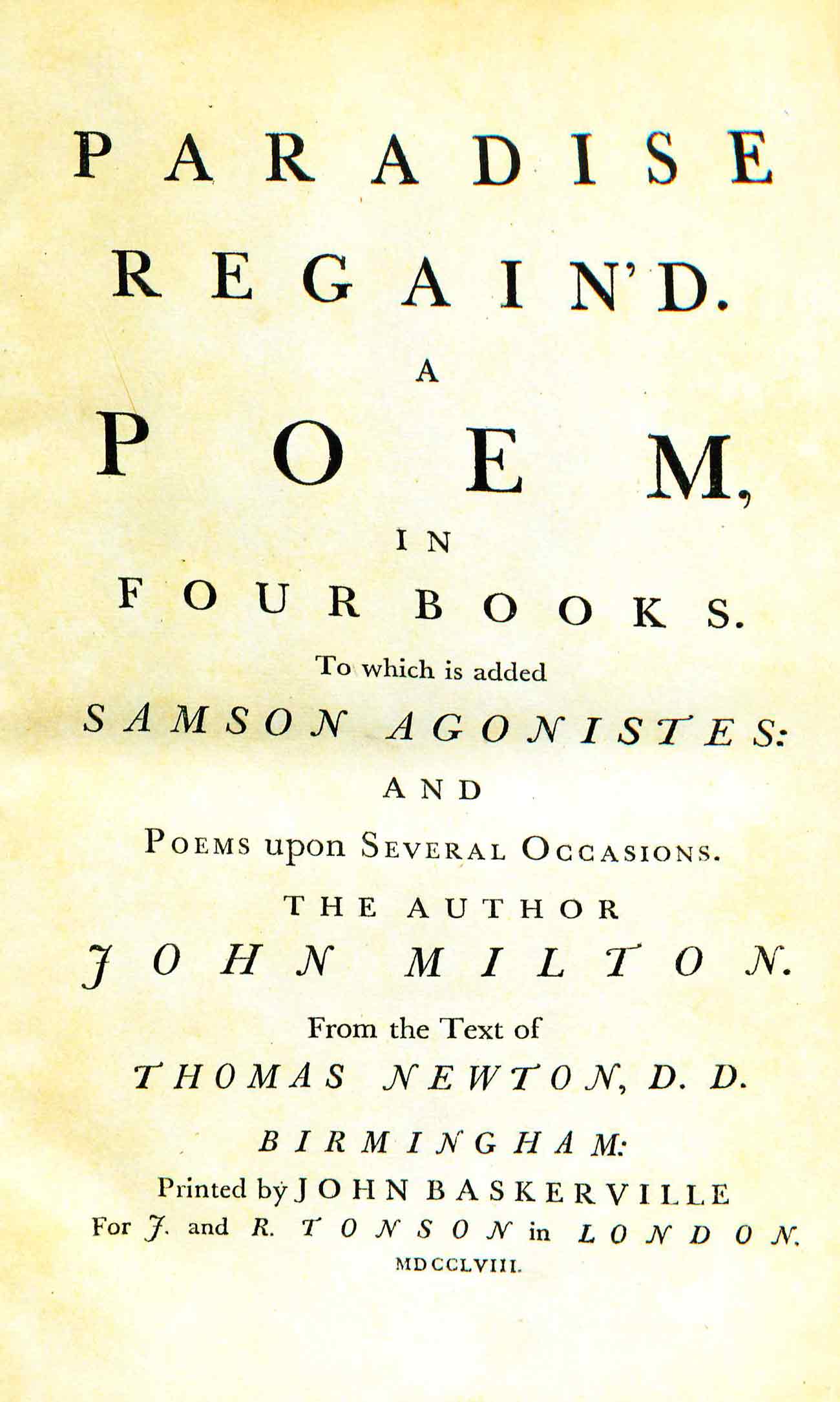

Title page from Paradise Regain'd, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | John Milton |

| Published | Birmingham: Printed by John Baskerville for J. and R. Tonson in London |

| Date | 1758 |

| Language | English |

| Pages | lxix, 390 p. |

| Desc. | 8vo (24 cm.) |

| Location | Shelf M-3 |

John Milton (1608-1674), was an English poet and polemicist, and a civil servant under Oliver Cromwell. Best known for his canonical epic poem, Paradise Lost, Milton began to write poetry in English and Latin at Cambridge in 1625.[1] From this early poetry one can see Milton's critical view of Catholicism. His first published poem was a commendatory poem in the second published folio of Shakespeare’s work in 1632, titled "On Shakespeare."[2]

Greatly affected by the deaths of his mother and his friend and fellow poet Edward King, Milton traveled abroad to Paris and throughout Italy in 1638.[3] When he returned to England, Milton published five anti-prelatical pamphlets that criticize the governance of the Church. With the dissolution of his first marriage in 1642 he began to write extensively on divorce, saying that the breakdown of a marriage should constitute grounds for divorce.[4]

Milton's career from 1641-1674 fluctuated between a focus on poetry, political and religious criticisms, and histories. Milton's political writings from 1649-1655 are marked by a disbelief in the divine right of kings, advocacy for a more republican government, and his controversial defense of regicide that made him infamous across Europe. He also wrote a formidable proposal for the reformation of the English education system[5], treatises on the importance of a free press, and a treatise against the use of tithes. After becoming blind in 1652, Milton began to dictate his writing.[6]

Milton's political writing in the 1650s controversially challenged monarchy as the best form of government. Instead, he advocated for a republic comprised of a "Grand or Supreme Council" of virtuous aristocrats. This political philosophy of "republican exclusivism" greatly influenced the United States' founding fathers, including Thomas Jefferson.[7] Jefferson specifically used Milton’s ideas that criticized the governance of the church to argue for the separation of church and state in Virginia.

Milton's books were ordered to be burned and he was imprisoned in the Tower after the restoration of Charles II. Milton dictated Paradise Lost from around 1658-1663. This epic poem presents the story of Genesis, with shockingly humanized depictions of God, Satan, Adam and Eve.

Published in 1671 as something of a sequel to Paradise Lost, Paradise Regained depicts the "temptations of Jesus in the desert" in an unsentimental way. Samson Agonistes was published along with this work, but it is unclear when Milton wrote this drama. Samson Agonistes is a play modeled after Greek dramas with clear autobiographical undertones[8], and a modern characterization of Samson as a man struggling to find divine influences in his life.

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as "Milton’s Paradise lost & regained. Baskerville. 2.v. 8[vo]." This was one of the titles kept by Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson sold a Baskerville set of Paradise Lost and Paradise Regain'd to the Library of Congress in 1815, but the volumes no longer exist to verify Wythe's prior ownership. Both George Wythe's Library[9] on LibraryThing and the Brown Bibliography[10] include the 1758 set based on Millicent Sowerby's use of that edition in Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson.[11] The Wolf Law Library followed Sowerby's recommendation and purchased a copy of the 1758 set for the George Wythe Collection.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in contemporary full calf with red and brown lettering labels, gilt.

Images of the library's copy of this book are available on Flickr. View the record for this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

See also

- A Complete Collection of the Historical, Political, and Miscellaneous Works of John Milton

- George Wythe Room

- Jefferson Inventory

- Paradise Lost

- Wythe's Library

References

- ↑ Gordon Campbell, "Milton, John (1608–1674)," Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004), accessed September 26, 2013. All biographical information is from this source unless otherwise noted.

- ↑ W.P. Trent, "John Milton," The Sewanee Review, 5, No. 1 (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1897), pp. 2-3.

- ↑ Pauline Lacy Smith, "John Milton as an Educator," Peabody Journal of Education, 23, no. 3 (Taylor & Francis, Ltd., Nov. 1945), pp. 170-71.

- ↑ Trent, pp. 8-9.

- ↑ Smith, p. 173.

- ↑ W.H. Wilmer, "The Blindness of Milton," The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 32, no. 3 (University of Illinois Press, Jul. 1993,) p. 308.

- ↑ Nathan R. Perl-Rosenthal, "The 'Divine Right of Republics': Hebraic Republicanism and the Debate over Kingless Government in Revolutionary America," The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, 66, No. 3 (Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Jul. 2009), p. 538.

- ↑ Smith, p. 172.

- ↑ LibraryThing, s. v. "Member: George Wythe", accessed on February 24, 2014.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

- ↑ E. Millicent Sowerby, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, (Washington, D.C.: The Library of Congress, 1952-1959), 4:424 [no.4288].

External Links

Read this book in Google Books.