Difference between revisions of "Rose v. Nicholas"

m |

m (→References) |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

[[Category:Cases]] | [[Category:Cases]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Contracts]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Procedure]] | ||

Revision as of 20:50, 4 April 2018

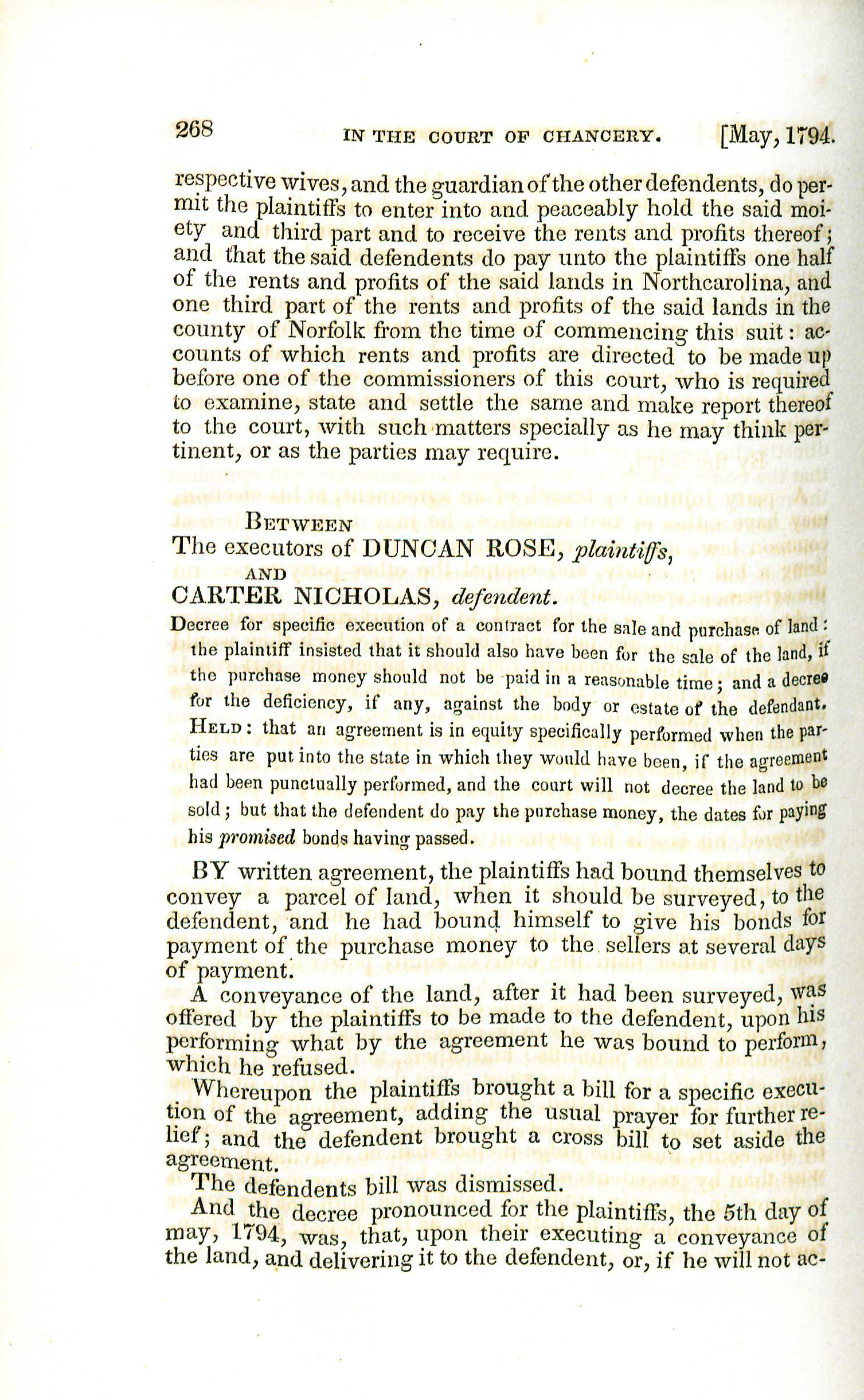

Rose v. Nicholas, Wythe 268 (1794),[1] discussed whether a court of equity could require the sale of land by the purchaser to satisfy the purchase price, even though that requirement was not in the original contract.

Background

The plaintiffs, executors of Duncan Rose's estate, signed a written contract to survey and sell a parcel of land to Carter Nicholas in exchange for several bonds. The plaintiffs surveyed the land and prepared to transfer ownership when Nicholas paid them. Nicholas, however, asked to cancel the deal.

The plaintiffs brought a bill (presumably to the High Court of Chancery) asking the court to require Nicholas to perform his part of the agreement. Nicholas filed a cross-bill asking the court to set aside the agreement. The court dismissed Nicholas's bill.

The Chancery Court issued a decree on May 5, 1794, enforcing specific performance of the contract. The plaintiffs would turn over the land to Nicholas, and Nicholas would pay the plaintiffs the amount specified in the contract plus interest dating from the payment dates the contract specified.

The plaintiffs asked the Chancery Court to add a requirement to the decree that if Nicholas did not pay them within a reasonable time, he would be forced to sell the land described in the contract to raise the money to pay the plaintiffs, and if the sale did not raise enough money to cover the debt, to authorize the enforcement of a judgment against Nicholas for the remainder.

The Court's Decision

The High Court of Chancery denied the plaintiffs' request for the extra requirement.

Wythe began by describing the differences between a remedy at law and a remedy at equity (as one would get at the Chancery Court) for a breach of contract. In a legal action, you can recover monetary damages for the injury; in an action at equity, you can force the other party to "specifically perform" the original agreement. The agreement is "specifically performed", according to Wythe, when the parties are in the situation they would have been in had the contract been performed as planned.

In the current case, Wythe said that "specific performance" would happen when the plaintiffs surveyed the land and conveyed it to Nicholas and Nicholas sealed and delivered his bonds for the purchase money to the plaintiffs. Under this scenario, Wythe questioned whether he had the power to issue a decree requiring Nicholas to sell the land to raise the rest of the purchase money the contract required. The plaintiffs submitted several English chancery court decisions arguing that Wythe had this power, but Wythe dismissed them, saying that they were not on point, and even if they were, he needed something besides caselaw precedent to convince him he had the power.

Wythe briefly examined the rationale for allowing courts of equity to require specific performance of a contract. A court of law can only award monetary damages for a breach of contract, and the court won't always be able to make those monetary damages equal to the harm suffered from the breach of contract. In such cases, a bill at equity provides an adequate remedy because requiring specific performance of the contract precisely negates the harm suffered from the breach of contract. Following this logic, an equitable remedy that does more than compensate for the harm suffered is no remedy at all, any more than the medicine for one disease would remedy a different disease.

Wythe looked at the wrong done to the plaintiffs: namely, that Nicholas refused to accept the deed to the land or transfer the bonds for payment to the plaintiffs. Requiring Nicholas to sell the land to satisfy the purchase price was not mentioned anywhere; instead, it would create another wrong by allowing the plaintiffs to profit twice from the same land - once from the proceeds from its sale (a sale which Nicholas contended would only bring in about half of the original purchase price) and another time through the decree against Nicholas for the rest of the purchase price.

The plaintiffs argued that their suggested addition to the decree left Nicholas the freedom for an indefinite to demand the land back when he paid the plaintiffs the remaining money due for the land plus interest, but Wythe found that unreasonable. He offered to amend the alternative decree in a different way, barring Nicholas from holding title to the land unless he paid the plaintiffs the money due within a specified period of time.

References

- ↑ George Wythe, Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852), 268.