Difference between revisions of "Literary Inquirer"

m (→See also) |

|||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

*[[American Biographical and Historical Dictionary]] | *[[American Biographical and Historical Dictionary]] | ||

*[[Biography of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence]] | *[[Biography of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence]] | ||

| + | *[[Discourse Refuting Statements|Discourse Refuting Statements Made That George Wythe at One Time Led a Life of Dissipation]] | ||

*[[Encyclopaedia Americana]] | *[[Encyclopaedia Americana]] | ||

*[[Eulogium on the Late Chancellor Wythe]] | *[[Eulogium on the Late Chancellor Wythe]] | ||

| + | *[[Jefferson-Sanderson Correspondence]] | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

Revision as of 08:56, 31 October 2016

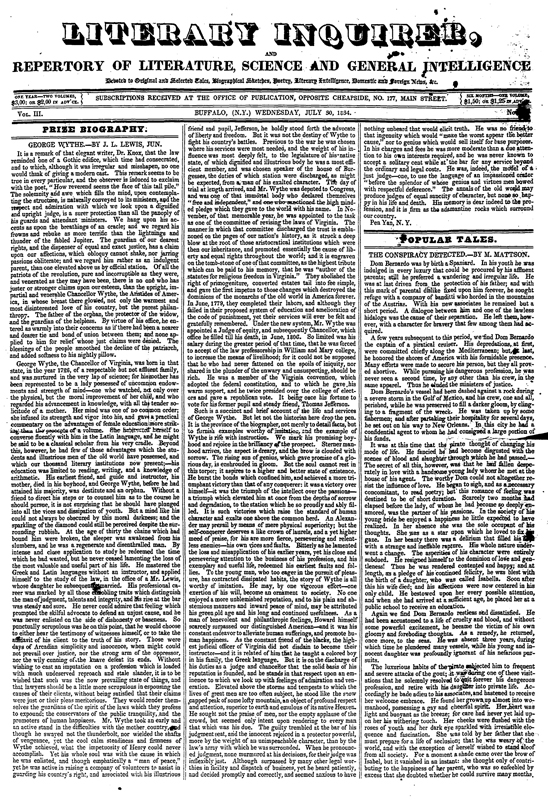

This early, prize-winning biography of George Wythe, was written by John L. Lewis, Jr., of Penn Yan, New York, for the Literary Inquirer of Buffalo,[1] edited by William Verrinder. Lewis would later become district attorney for Yates County, New York.[2]

Lewis does not cite any sources, but he probably made use of available encyclopedic articles, such as the Encyclopædia Americana, or Lempriere's Universal Biography. His prose, however, is more florid and his tone is of the more didactic sort, like that in the American Gleaner. Lewis unfortunately repeats the notion found in available sources that Wythe "plunged into all the vices and dissipation of youth" after the deaths of his parents. This story has been disproved by later scholars.[3] Interestingly, Lewis refers to Wythe as the "Aristides of America"; previously, only Governor John Tyler had compared Wythe to Aristides, in a letter to Thomas Jefferson, in 1810.[4]

Article text, 30 July 1834

Page 13

PRIZE BIOGRAPHY

GEORGE WYTHE.— BY J.L. LEWIS, JUN.

It is a remark of that elegant writer, Dr. Knox, that the law reminded one of a Gothic edifice, which time has consecrated, and to which, although it was irregular and misshapen, no one would think of giving a modern cast.[5] This remark seems to be true in every particular, and the observer is induced to exclaim with the poet, "How reverend seems the face of this tall pile."[6] The solemnity and awe which fill the mind, upon contemplating the structure, is naturally conveyed to its ministers, and the respect and admiration with which we look upon a dignified and upright judge, is a surer protection than all the panoply of his guards and attendant ministers. We bang upon his accents as upon the breathings of an oracle; and we regard his frowns and rebuke as more terrific than the lightnings and thunder of the fabled Jupiter. The guardian of our clearest rights, and the dispenser of equal and exact justice, has a claim upon our affections, which obloquy cannot shake, nor jarring passions obliterate; and we regard him rather as an indulgent parent, than one elevated above us by official station. Of all the patriots of the revolution, pure and incorruptible as they were, and venerated as they may have been, there is no one who has juster or stronger claims upon our esteem, than the upright, impartial and venerable Chancellor Wythe, the Aristides of America, in whose breast there glowed, not only the warmest and most disinterested love of his country, but the purest philanthropy. The father of the orphan, the protector of the widow, and the guardian of the helpless. By virtue of his office, he entered as warmly into their concerns as if there had been a nearer and dearer tie and bond of union between them; and none applied to him for relief whose just claims were denied. The blessings of the people smoothed the decline of the patriarch, and added softness to his nightly pillow.

George Wythe, the Chancellor of Virginia, was born in that state, in the year 1726, of a respectable but not affluent family, and was nurtured in the very lap of science; for his mother has been represented to be a lady possessed of uncommon endowments and strength of mind—one who watched, not only over the physical, but the moral improvement of her child, and who regarded his advancement in knowledge, with all the tender solicitude of a mother. Her mind was one of no common order; she infused its strength and vigor into his, and gave a practical commentary on the advantages of female education more striking than the precepts of a volume. She habituated herself to converse fluently with him in the Latin language, and he might be said to be a classical scholar from his very cradle. Beyond this, however, he had few of those advantages which the students and illustrious men of the old world have possessed, and which our thousand literary institutions now present;—his education being limited to reading, writing, and a knowledge of arithmetic. His earliest friend, and guide and instructor, his mother, died in his boyhood, and George Wythe, before he had attained his majority, was destitute and an orphan. Without a friend to direct his steps or to counsel him as to the course he should pursue, it is not surprising that he should have plunged into all the vices and dissipation of youth. But a mind like his could not always be obscured by this moral darkness; and the sparkling of the diamond could still be preceived despite the surrounding rubbish. At the age of thirty the chains which had bound him were broken, the sleeper was awakened from his slumbers, and he was a regenerated and disenthralled man. By intense and close application to study he redeemed the time which he had wasted, but he never ceased lamenting the loss of the most valuable and useful part of his life.[7] He mastered the Greek and Latin languages without an instructor, and applied himself to the study of law, in the office of a Mr. Lewis, whose daughter he subsequently married.[8] His professional career was marked by all those ennobling traits which distinguish the man of judgment, talents, and integrity, and his rise at the bar was steady and sure. He never could admire that feeling which prompted the skilful advocate to defend an unjust cause, and he was never enlisted on the side of dishonesty or baseness. So punctually scrupulous was he on this point, that he would choose to either hear the testimony of witnesses himself, or to take the affidavit of his client to the truth of his story. Those were days of Arcadian simplicity and innocence, when might could not prevail over justice, nor the strong arm of the oppressor, nor the wily cunning of the knave, defeat its ends. Without wishing to cast an imputation on a profession which is loaded with much undeserved reproach and stale slander, it is to be wished that such was now the prevailing state of things, and that lawyers should be a little more scrupulous in espousing the cause of their clients, without being satisfied that their claims were just or their pleas meritorious. They would render themselves the guardians of the spirit of the laws which they profess to expound; the conservators of the public tranquility, and the promoters of human happiness. Mr. Wythe took an early, and an active stand in the difficulties with the mother country, and though he swayed not the thunderbolt, nor wielded the shafts of vengeance, yet the cool, calm steadiness and firmness of Wythe achieved, what the impetuosity of Henry could never accomplish. Yet his whole soul was with the cause in which he was enlisted, and though emphatically a "man of peace," yet he was active in raising a company of volunteers to assist in guarding his country's right, and associated with his illustrious friend and pupil Jefferson, he boldly stood forth the advocate of liberty and freedom. But it was not the destiny of Wythe to fight his country's battles. Previous to the war he was chosen where his services were most needed, and the weight of his influence was most deeply felt, to the legislature of his native state, of which dignified and illustrious body he was the most efficient member, and was chosen speaker of the house of Burgesses, the duties of which station were discharged, as might be expected, from a man of his exalted character. The day of trial at length arrived, and Mr. Wythe was deputed to Congress, and was one of that immortal body who declared themselves "free and independent," and one who sanctioned the high minded pledge which they gave to the world with his name. In November, of that memorable year, he was appointed to the task as one of the committee of revising the laws of Virginia. The manner in which that committee discharged the trust is emblazoned on the pages of our nation's history, as it struck a deep blow at the root of those aristocratical institutions which were then our inheritance, and promoted essentially the cause of liberty and equal rights throughout the world; and it is engraven on the tomb-stone of one of that committee, as the highest tribute which can be paid to his memory, that he was "author of the statutes for religious freedom in Virginia."[9] They abolished the right of primogeniture, converted estates tail into fee simple, and gave the first impetus to those changes which destroyed the dominions of the monarchs of the old world in America forever. In June, 1779, they completed their labors, and although they failed in their proposed system of education amelioration of the code of punishment, yet their services will ever be felt and gratefully remembered. Under the new system, Mr, Wythe was appointed a Judge of equity, and subsequently Chancellor, which he filled till his death, in June, 1806. So limited was his salary during the greater period of that time, that he was forced to accept of the law professorship in William and Mary college, to increase the means of livelihood; for it could not be supposed that he who had never fattened on the spoils of iniquity, nor shared in the plunder of the unwary and unsuspecting, should be rich. He was a member of the Virginia convention, which adopted the federal constitution, and to which he gave his warm support, and he twice presided over the college of electors and gave a republican vote. It being once his fortune to vote for his former pupil and steady friend, Thomas Jefferson.

Such is a succinct and brief account of the life and services of George Wythe. But let not the historian here drop the pen. It is the province of the biographer, not merely to detail facts, but to furnish examples worthy of imitation, and the example of Wythe is rife with instruction. We mark his promising boyhood and rejoice in the brilliancy of the prospect. Sterner manhood arrives, the aspect is dreary, and the brow is clouded with sorrow. The rising sun of genius, which gave promise to a glorious day, is enshrouded in gloom. But the soul cannot rest in this torpor; it aspires to a higher and better state of existence. He burst the bonds which confined him, and achieved a more triumphant victory than that of any conquerer: it was a victory over himself—it was the triumph of the intellect over the passions—a triumph which elevated him at once from the depths of sorrow and degradation, to the station which he so proudly and ably filled. It is such victories which raise the standard of human character and exalts one above the common herd. An Alexander may prevail by means of mere physical superiority; but the self-conquerer deserves a like crown of laurels, and a yet higher meed of praise, for his are more fierce, persevering and relentless enemies—his own vices and faults. Bitterly as he lamented the loss and misapplication of his earlier years, yet his close and and persevering attention to the business of his profession, and his exemplary and useful life, redeemed his earliest faults and follies. To the young man, who too eager in the pursuit of pleasure, has contracted dissipated habits, the story of Wythe is all worthy of imitation. He may, by one vigorous effort—one exertion of his will, become an ornament to society. No one enjoyed a more unblemished reputation, and to his plain abstemious manners and inward peace of mind, may be attributed his green old age and his long continued usefulness. As a man of benevolent and philanthropic feelings, Howard[10] himself scarcely surpassed our distinguished American—and it was his constant endeavor to alleviate human sufferings, and promote human happiness. But it is on the discharge of his duties as a judge and chancellor that the solid basis of his reputation is founded, and he stands in that respect upon an eminence to which we look up with feelings of admiration and veneration. Elevated above the storms and tempests to which the lives of great men are too often subject, he stood like the snow capped peak of some lofty mountain, an object of profound respect and attention, superior to earth and emulous of its native Heaven. He sought not the praise of men, nor the empty applause of the crowd, but seemed only intent upon rendering to every man that which was his due. The guilty trembled at the bar of his judgment seat, and the innocent rejoiced in a protecter powerful, more by the weight of an unimpeachable character, than by the law's array with which he was surrounded. When he pronounced judgment, none murmured at his decisions, for their judge was inflexibly just. Although surpassed by many other legal worthies in facility and dispatch of business, yet he heard patiently, and decided promptly and correctly, and seemed anxious to have nothing unheard that would elicit truth. He was no friend to that ingenuity which would "make the worse appear the better cause,"[11] nor to genius which would sell itself for base purposes. In his charges and fees he was more moderate than a due attention to his own interests required, and he was never known to accept a solitary cent while at the bar for any service beyond the ordinary and legal costs. He was, indeed, the model of a just judge—one, to use the language of an impassioned orator "before the splendor of whose genius and virtues men bowed with respectful deference."[12] The annals of the old world may produce judges of equal sanctity of character, but none so happy in his life and death. His memory is dear indeed to the profession, and it is firm as the adamantine rocks which surround our country.

- Pen Yan, N.Y.

See also

See also

- American Biographical and Historical Dictionary

- Biography of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence

- Discourse Refuting Statements Made That George Wythe at One Time Led a Life of Dissipation

- Encyclopaedia Americana

- Eulogium on the Late Chancellor Wythe

- Jefferson-Sanderson Correspondence

External links

- Read this article in Google Books.

References

- ↑ J.L. Lewis, Jr., "Prize Biography: George Wythe," Literary Inquirer, and Repertory of Literature, Science and General Intelligence 3, no. 2 (30 July 1834), 13. Reprinted in the Rural Repository 13 (New Series 4), no. 11 (5 November 1836), 85-86.

- ↑ O.L. Holley, ed., New York State Register for 1845 (New York: J. Disturnell, 1845), 480.

- ↑ Allan D. Jones, "The Character and Service of George Wythe," Virginia State Bar Association Reports 44 (1932), 326-328; William Edwin Hemphill, "George Wythe the Colonial Briton: A Biographical Study of the Pre-Revolutionary Era in Virginia" (PhD diss., University of Virginia, 1937), 82-83; and Leon M. Bazile, "Discourse Refuting Statements Made That George Wythe at One Time Led a Life of Dissipation," n.d., Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia.

- ↑ John Tyler, Sr., to Thomas Jefferson, November 12, 1810.

- ↑ Vicesimus Knox (1752 – 1821), author of Essays, Moral and Literary (1778); although Blackstone wrote, in a 1745 letter to Seymour Richmond (reprinted in The Legal Observer 1, no. 1 (6 November 1830), 11-12):

I have sometimes thought that ye Common Law, as it stood in Littleton's Days, resembled a regular Edifice: where ye Apartments were properly disposed, leading one into another without Confusion, where every part was subservient to ye whole, all uniting in one beautiful Symmetry: & every Room hod its distinct Office allotted to it. But as it is now, swoln, shrunk, curtailed, enlarged, altered, & mangled, by various & contradictory Statutes, &c; it resembles ye same Edifice, with many of its most useful Parts pulled down, with preposterous Additions in other Places, of different Materials and coarse workmanship: according to ye Whim, or Prejudice, or private Convenience of ye Builders. By wch. means the Communication of ye Parts is destroyed, and their Harmony quite annihilated; & now it remains a huge, irregular Pile, with many noble Apartments, tho' awkwardly put together, & some of them of no visible Use at present. But if one desires to know why they were built, to what End or Use, how they communicated with ye rest, and ye like; he must necessarily carry in his Head ye Model of ye old House, wch. will be ye only Clew to guide him thro' this new Labyrinth.

- ↑ William Congreve, The Mourning Bride (1703).

- ↑ Wythe lamented not studying Greek during the early years of his career as an attorney, but the idea that he led a life of 'vices and dissipation' has been disproved by Jones, Hemphill, and Bazile.

- ↑ Zachary Lewis (1701 – 1765), prominent lawyer of Spotsylvania Co., Virginia. See Horace Edwin Hayden, Virginia Genealogies (Wilkes-Barre, PA: E.B. Yordy, 1891), 381.

- ↑ Jefferson wrote the epitaph for the monument on his grave at Monticello: "Here was buried Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of American Independence, of the statute of Virginia for for religious freedom, and father of the University of Virginia."

- ↑ John Howard (1726 – 1790), British philanthropist, prison reformer, and Fellow of the Royal Society.

- ↑ Rufus King to James Madison, 27 January 1788: "The Opposition complain that the Lawyers, Judges, Clergymen, Merchants and men of Education are all in Favor of the constitution, and that for this reason they appear to be able to make the worst appear the better cause...[.]" Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Robert Emmet (1778 – 1803), Irish nationalist, spoken at his trial before his execution for high treason.