Difference between revisions of "Teacher of Jefferson and Marshall"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE:"The Teacher of Jefferson and Marshall"}} | {{DISPLAYTITLE:"The Teacher of Jefferson and Marshall"}} | ||

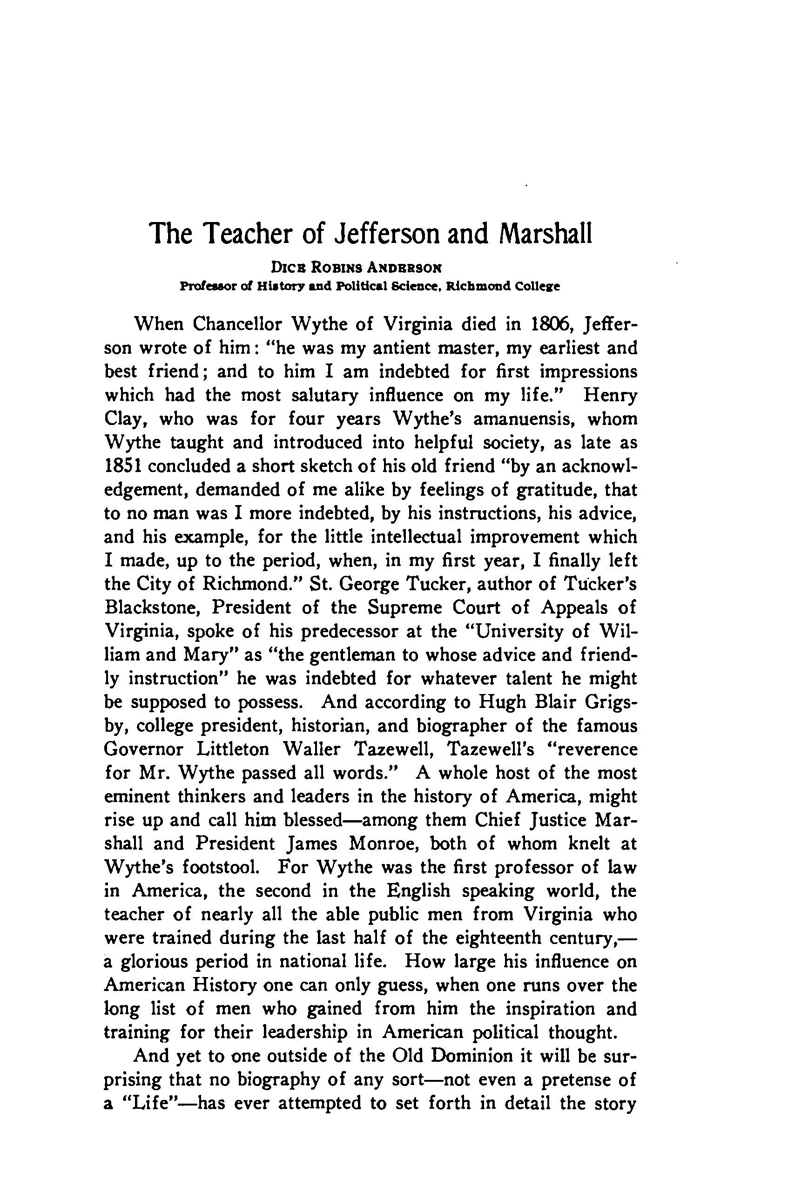

[[File:AndersonTeacherOfJeffersonAndMarshallOctober1916P327.jpg|thumb|right|400px|First page of D.R. Anderson's article, "The Teacher of Jefferson and Marshall," from the ''South Atlantic Quarterly'' (October 1916).]] | [[File:AndersonTeacherOfJeffersonAndMarshallOctober1916P327.jpg|thumb|right|400px|First page of D.R. Anderson's article, "The Teacher of Jefferson and Marshall," from the ''South Atlantic Quarterly'' (October 1916).]] | ||

| + | "[[Media:AndersonTeacherOfJeffersonAndMarshallOctober1916.pdf|The Teacher of Jefferson and Marshall]]" is a 1916 article from the ''South Atlantic Quarterly'' by D.R. Anderson.<ref>Dice Robins Anderson, [[Media:AndersonTeacherOfJeffersonAndMarshallOctober1916.pdf|"The Teacher of Jefferson and Marshall,"]] ''Southern Atlantic Quarterly'' 15, no. 4 (October 1916), 327-343.</ref> | ||

Born in Charlottesville, Virginia, Dice Robins Anderson (1880 – 1942) was a scholar of Virginia history and an academic. Most notably, Anderson was Professor of History and Political Science at Richmond College (later, Richmond University) from 1909 to 1919, during which time he received his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in 1912. From 1919 until 1921 he was director of the School of Business Administration at Richmond, when he left to become President of Randolph-Macon Woman's College, a position he held until 1931.<ref>Robert S. Alley, "Anderson, Dice Robins," in ''Dictionary of Virginia Biography,'' vol. 1, eds. John T. Kneebone, J. Jefferson Looney, Brent Tarter, and Sandra Gioia Treadway (Richmond, VA: Library of Virginia, 1998), 130-131.</ref> | Born in Charlottesville, Virginia, Dice Robins Anderson (1880 – 1942) was a scholar of Virginia history and an academic. Most notably, Anderson was Professor of History and Political Science at Richmond College (later, Richmond University) from 1909 to 1919, during which time he received his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in 1912. From 1919 until 1921 he was director of the School of Business Administration at Richmond, when he left to become President of Randolph-Macon Woman's College, a position he held until 1931.<ref>Robert S. Alley, "Anderson, Dice Robins," in ''Dictionary of Virginia Biography,'' vol. 1, eds. John T. Kneebone, J. Jefferson Looney, Brent Tarter, and Sandra Gioia Treadway (Richmond, VA: Library of Virginia, 1998), 130-131.</ref> | ||

| Line 6: | Line 7: | ||

In 1915, Anderson founded the short-lived ''Richmond College Historical Papers,'' and the same year published ''William Branch Giles: A Study in the Politics of Virginia and the Nation from 1790-1830'' (Menasha, WI: Banta Pub. Co.), an extended version of his Ph.D. dissertation. In 1924, Anderson was the speaker at the College of William & Mary's Commencement ceremonies, where he was given an LL.D.<ref>[http://scdb.swem.wm.edu/wiki/index.php/Commencement_Speakers "Commencement Speakers,"] Special Collections Research Center Wiki, Swem Library.</ref> | In 1915, Anderson founded the short-lived ''Richmond College Historical Papers,'' and the same year published ''William Branch Giles: A Study in the Politics of Virginia and the Nation from 1790-1830'' (Menasha, WI: Banta Pub. Co.), an extended version of his Ph.D. dissertation. In 1924, Anderson was the speaker at the College of William & Mary's Commencement ceremonies, where he was given an LL.D.<ref>[http://scdb.swem.wm.edu/wiki/index.php/Commencement_Speakers "Commencement Speakers,"] Special Collections Research Center Wiki, Swem Library.</ref> | ||

| − | Anderson published several articles concerning [[Thomas Jefferson]] and [[George Wythe]] in 1916, including "[[Jefferson and the Virginia Constitution]]" in the ''American Historical Review,'' "Chancellor Wythe and Parson Weems" in the ''William and Mary College Quarterly,'' and "The Teacher of Jefferson and Marshall | + | Anderson published several articles concerning [[Thomas Jefferson]] and [[George Wythe]] in 1916, including "[[Jefferson and the Virginia Constitution]]" in the ''American Historical Review,'' "Chancellor Wythe and Parson Weems" in the ''William and Mary College Quarterly,'' and "The Teacher of Jefferson and Marshall": |

==Article text, October 1916== | ==Article text, October 1916== | ||

Revision as of 12:49, 21 February 2016

"The Teacher of Jefferson and Marshall" is a 1916 article from the South Atlantic Quarterly by D.R. Anderson.[1]

Born in Charlottesville, Virginia, Dice Robins Anderson (1880 – 1942) was a scholar of Virginia history and an academic. Most notably, Anderson was Professor of History and Political Science at Richmond College (later, Richmond University) from 1909 to 1919, during which time he received his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in 1912. From 1919 until 1921 he was director of the School of Business Administration at Richmond, when he left to become President of Randolph-Macon Woman's College, a position he held until 1931.[2]

In 1915, Anderson founded the short-lived Richmond College Historical Papers, and the same year published William Branch Giles: A Study in the Politics of Virginia and the Nation from 1790-1830 (Menasha, WI: Banta Pub. Co.), an extended version of his Ph.D. dissertation. In 1924, Anderson was the speaker at the College of William & Mary's Commencement ceremonies, where he was given an LL.D.[3]

Anderson published several articles concerning Thomas Jefferson and George Wythe in 1916, including "Jefferson and the Virginia Constitution" in the American Historical Review, "Chancellor Wythe and Parson Weems" in the William and Mary College Quarterly, and "The Teacher of Jefferson and Marshall":

Contents

Article text, October 1916

Page 327

The Teacher of Jefferson and Marshall

DICE ROBINS ANDERSON

Professor of History and Political Science, Richmond CollegeWhen Chancellor Wythe of Virginia died in 1806, Jefferson wrote of him: "he was my antient master, my earliest and best friend; and to him I am indebted for first impressions which had the most salutary influence on my life." Henry Clay, who was for four years Wythe's amanuensis, whom Wythe taught and introduced into helpful society, as late as 1851 concluded a short sketch of his old friend "by an acknowledgement, demanded of me alike by feelings of gratitude, that to no man was I more indebted, by his instructions, his advice, and his example, for the little intellectual improvement which I made, up to the period, when, in my first year, I finally left the City of Richmond." St. George Tucker, author of Tucker's Blackstone, President of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, spoke of his predecessor at the "University of William and Mary" as "the gentleman to whose advice and friendly instruction" he was indebted for whatever talent he might be supposed to possess. And according to Hugh Blair Grigsby, college president, historian, and biographer of the famous Governor Littleton Waller Tazewell, Tazewell's "reverence for Mr. Wythe passed all words." A whole host of the most eminent thinkers and leaders in the history of America, might rise up and call him blessed—among them Chief Justice Marshall and President James Monroe, both of whom knelt at Wythe's footstool. For Wythe was the first professor of law in America, the second in the English speaking world, the teacher of nearly all the able public men from Virginia who were trained during the last half of the eighteenth century,— a glorious period in national life. How large his influence on American History one can only guess, when one runs over the long list of men who gained from him the inspiration and training for their leadership in American political thought.

And yet to one outside of the Old Dominion it will be surprising that no biography of any sort—not even a pretense of a "Life"—has ever attempted to set forth in detail the story

Page 328

of this great teacher, statesman, judge, moulder of thought and of men. To Virginians, however, it is not surprising, for despite our boast of ancestry and pride in the contribution of the "grand old Commonwealth" to national greatness, we have not been forward in setting forth our claims in works of convincing scholarship. We have allowed "aliens" to write the history of our great men, and then, in the way of the world, complained of the "aliens" because they have not done it to our satisfaction. We are so justly confident of our place, that we see no reason why monuments should not everywhere be erected to our great characters whose reputation, of course, must be part of the subconscious accumulations of heathen New Englanders. But we should not be blamed too much for our unwillingness to sweat over the prosy task of giving evidence for the faith that is in us. For we have had, since 1865, to work without faltering for our very living, and have had little time or money for that painstaking scholarship demanded by the historical public. Now we are glorying in material victory, and find it necessary to make material victory greater.

But a new day is dawning, a new scholarship is developing, and the future will see many attractive and well wrought biographies and histories written south of the Potomac by men, who, unfortunately, have neither time nor money, only love for the truth—and ambition.

About Chancellor Wythe, there was an absence of the dramatic, apparently; of the spectacular; of the opportunity for advertisement. For he was not conspicuous as a soldier. The eminent soldier—sometimes the soldier that is not eminent—draws the biographer like a magnet. And although Wythe knew politics deeply, he was in no sense a skilled politician. Although, too, he was truly a great statesman, great in the estimation of his contemporaries, and not less than great in his influence on state and national institutions, he left no volumes of orations and kept himself out of the stilted newspapers of his day. His supreme greatness shone as a judge and as a teacher, and great judges—unless they be at once great politicians—and great teachers have not been favorites with those who help to increase the endless multitude of

Page 329

books. In Wythe one must find a quiet, dignified, very learned, lovable and loving man who will live to fame as an able and virtuous jurist and as an inspiring teacher of the law. His chief aim, as he wrote in 1783 to his dear friend John Adams, was: "to form such characters as may be fit to succeed those which have been ornamental and useful in the national councils of America."

Most readers have not over-much friendliness to biographical details. But I am sure if they read this article at all, they will expect the author to save them the trouble of looking up the catalogue of dates and names which we seem to associate with a biographical study. For such readers one must say, in the conventional way, that George Wythe was born in 1726, in Elizabeth City County, Virginia, and that he was the son of Thomas Wythe, delegate in the House of Burgesses; grandson of Thomas Wythe, one of the first trustees of Hampton; and great-grandson of Thomas Wythe, the immigrant of 1680. And one may add that his mother was Margaret Walker, daughter of George Walker and Ann Keith, and for those of clerical interests, report that Ann Keith was the daughter of George Keith, Quaker preacher, mathematician, the first missionary to America sent by the "Society for Propagating the Gospel in Foreign Parts." The three "R's" he learned at school; his first acquaintance with Latin and Greek he received from his mother, who, however, knew of Greek only the alphabet and how to hold the dictionary; and a little finish he put on during a short stay at William and Mary College. Wythe, however, was preeminently a self-educated man. He had a passion for knowledge, scientific and classical, and an industry which hesitated at no labor to acquire knowledge. To all he was the "learned judge," or the "learned" Mr. Wythe. He studied law in the usual way of those days, in the offices of lawyers, and, in a manner not beyond imitation in our own time, married the daughter of one of his teachers, Ann Lewis, daughter of John Lewis of Spottsylvania County. He went through a few years of dissipation, much exaggerated in all probability by those who have written their little homilies on him, for in 1748 he was clerk of the Committee of Privileges and Elections of the House of

Page 330

Burgesses, in 1754 he was Attorney General of the Colony during the absence of Peyton Randolph in England, and in 1758 member of the House from the College of William and Mary. From that time on till 1778 he was associated with the House of Burgesses and its successor, the House of Delegates, almost continuously as member from Williamsburg or Elizabeth City County, or as clerk protecting the journal from the Governor, or as speaker in 1777, put in by Jefferson, to help through reform legislation. In the course of this period, he was delegate in the Continental Congress and as such friend of John Adams, advocate of free trade and a Confederation, and signer of the Declaration of Independence. In 1776, likewise, he took an important part in framing the first Constitution of Virginia, and helped design the seal of the state. It was he who brought home from Philadelphia the draft of the Constitution which Jefferson had made, and among his papers it was found. It was Wythe, too, who induced John Adams to write his "Thoughts on Government" and Wythe was the "friend" to whom it is addressed. He was one of the three authors of the famous report of the revisors in 1779, famous because of its advanced suggestions for the promotion of education, the abolition of entails and primogeniture, the gradual emancipation of slaves, and the establishment of religious liberty,—a report described in glowing terms in all the biographies of Jefferson. The same year that the report of the revisors was made, he became, under Jefferson's plan of reorganization for the college, the Professor of Law and Police. The year before saw him installed as one of the Chancery Judges of the State. The position of Chancery Judge, or at one time, sole Chancellor, he held till his death in 1806.

In 1787, he accompanied his friends, Washington, Madison, Edmund Randolph, Dr. James McClurg, George Mason, John Blair to Philadelphia to help frame a national constitution. And the following year he gave his great influence to the work of defeating the plans of Patrick Henry for delaying the ratification of the constitution until amendments had been tacked on. Wythe presided over the Committee of the Whole in the Convention that met in Richmond in 1788; and when victory

Page 331

was won he brought in the list of amendments desired by Virginia at the earliest moment. The amount of Wythe's influence in this or any other body is hard to compute—for he did not make speeches or attempt political sleight of hand. But in the computation one must not omit these factors: that he was considered the most learned man in the state, that he was surrounded by his old pupils and friends; that he was cherished with a deep and tender affection such as few could command.

The rest of Wythe's life flowed along quietly and simply—in study, in teaching, in grave attention to deadening chancery papers, in undeviating idolatry of Jefferson, whose will he did; in charity, in love and harmony with his neighbors, except his lifelong rival, Edmund Pendleton; until finally he fell a victim to the poisoning hand of a grand-nephew on June 8, 1806. These are the simple annals of the learned, the wise, and the virtuous Mr. Wythe—or "Dr." Wythe, for he, like Benjamin Franklin and James Madison, honored the degree of Doctor of Laws from William and Mary; the degree could do them no honor.

Bishop Meade in his "Old Churches, Ministers, and Families of Virginia," quotes another preacher, Rev. Lee Massey, as saying Wythe was the only "honest lawyer he ever knew." One may, however, suspect the good preacher of exaggeration; a loyal Virginian would find difficulty in admitting the unique claim, because it would doom every other man of the period to the reputation of dishonesty. In Wythe's day, as in the days "before the war" Virginia was a state of lawyers. Many of them, too, were men of genuine ability and of incorruptible honor. Some may not have been. But of one thing we may be certain that there was never a breath of scandal about the legal career of George Wythe from the time he began to practice in 1746 till 1778 when he became Chancellor, and during his honorable career as judge down to 1806 when he died. About the details of his practice we know very little, but he was one of the leading lights of the colonial courts before which he practiced. A few and only a few of his arguments have been handed down, and these in the reports which Jefferson collected.

Page 332

We wish there was more about the details of the practice of the brilliant men of those days. Law was in those innocent times a most attractive profession. Personality and oratorical ability counted for much; more, no doubt, than they do in this day of legal specialization and large office practice. Startling things were always happening. Stirring appeals and massive logic were nothing unusual when Wythe and Pendleton, John and Peyton Randolph hurled their thunderbolts at one another, or in that day a little later when Patrick Henry and John Marshall, John Wickham and Daniel Call matched their noble abilities and characters as well.

The great rival of Wythe was Edmund Pendleton, the distinguished patriot and statesman of national fame. And this rivalry, begun in practice at the colonial bar, continued with no little ill-feeling when they had come to the highest judicial offices in the new state. In the opening of a case, in the concise statement of the facts, in the sturdy delivery of legal learning and argument before the court, Wythe was a master. But in fluency of language, in control over the feelings of a jury, in ability to wrest a verdict, he was at a disadvantage in the contest with the alert, quick-witted Pendleton, and he felt it. On one occasion after receiving discomfiture at the hands of his wily opponent, in discouragement he declared that he was going to throw up the law, go home, take orders, and preach the gospel. A friend with more humor than Wythe possessed, playfully added, "Yes, and then Pendleton will go home, give up law, take orders, preach the gospel and beat you there."

Wythe's conception of legal ethics, as we have said, was exalted—but legal ethics is a most elusive subject and none but a Philadelphia lawyer is able to state in terms smooth enough for the public and safe enough for the lawyer the moral obligations of the profession. What cases the attorney should undertake, what are the legitimate methods of advancing his client's interest none but the client and the lawyer should, I suppose, say. But a far distant observer, cautiously expressing his views after slight experience might be pardoned for advancing the opinion that, of the two, lawyer and client, the client is likely to be the more unscrupulous. Has not Mr. Bradford in the Atlantic told us the story of the titantic south-

Page 333

ern genius of ante-bellum days? Approaching Robert Toombs on the possibility of the collection of a claim, a would-be client received from the fierce old Georgian the answer, "you can collect this claim but you should not. This is a case where the law and justice are on different sides." And when the client insisted on proceeding to secure judgment from the court, Toombs shut him up with the thunderous: "Then hire somebody else to assist you in your damned rascality."

I think, however, Wythe is unique in the history of the legal profession in one respect: he took a perfect delight in receiving small fees. No one was allowed to overpay him—more than he thought he had earned he gave back. Did any other lawyer ever receive more than he thought he had earned—even Robert Toombs? Not a dirty coin, it is said, ever reached the bottom of the pockets of the Georgia lawyer, and I thing it is true not one ever reached the bottom of the pocket of the Virginian, George Wythe. A case that seemed to him unjust he rejected, doubtful statements made to him by clients had to be repeated under oath. The learning and abilities of good old Chancellor Wythe, so far as he could help it, were never prostituted to gratify the passions of the greedy, never became the midnight tools of those who would undermine the temple of justice.

The beginning of Wythe's judicial experience was as one of the justices who held court, in the old Virginia way, in Elizabeth City County. And at least one case was decided by these justices that is of national importance. Everybody knows by heart the famous Parsons' Case argued in 1763 by Patrick Henry before the justices of Hanover County, but few know of the Parson's Case decided that same year in Elizabeth City County—the case of Warrington (the parson) vs. Jiggitts. The record reads quaintly:

- "Wednesday the 2d of March 1763

- Presdt George Wythe * * *

Warrington vs. Jiggitts—the matter of law arising on a specl verdt being this day argued It seems to the court that by virtue of the Act of the Assembly made etc. that the Law is for the Deft and Judgt for the Deft from wch Judgment the Plt prayed an appeal to the 19th day of the next General

Page 334

Court upon his entering into Bond with security between this and the next court." There seems, however, to have been no Patrick Henry to give this Parson's Case the fame it deserves. When the High Court of Chancery was created in 1777, of the three judges Wythe became one. The sessions were at Williamsburg, the jurisdiction all but unlimited in both original and appellate cases, the terms were two a year, the salary was £500. Eleven years later the judges were reduced to one, the terms were increased to four, the jurisdiction of the court extended over the whole state, Richmond was the seat of its sessions. George Wythe, sole chancellor, soon removed from Williamsburg to Richmond, occupying a residence on the corner of Fifth Street and Grace—a spot now marked in his honor. In 1802 three districts were created with superior courts of chancery in each, holding their sessions respectively at Richmond, Williamsburg, and Staunton. George Wythe remained the chancellor at Richmond. This was the arrangement until his death.

The reasons for the appointment of Wythe are given by Beverly Tucker, son of St. George Tucker, who was quoted at the beginning of this article, and like his father, "Professor of Law in the University of William and Mary." In a book published in 1846 on the "Principles of Pleading," he describes the intention of the fathers in 1777 when the higher courts were established in the state. "The difficulty," he says, "was to find the men fit to fill these important posts. Integrity and talent were abundant, but a learned lawyer was indeed a rara avis. What motive had the lawyers had to acquire learning? With the exception of some few who had studied the profession abroad, and had not been long enough in Virginia to lose the memory of what they knew, in the loose practice prevailing here, there was but one man in the state who had any claims to the character. I speak of the venerable Chancellor Wythe, a man who differed from his contemporaries in this, because in his ordinary motives and modes of action he differed altogether from other men. Without ambition, without avarice, taking no pleasure in society, he was by nature and habit addicted to solitude, and his active mind found its only enjoyment in profound research. The language of antiquity, the

Page 335

exact sciences, and the law, were the three studies which alone could be pursued with a reasonable hope of arriving at that certainty, which his upright and truth loving mind contemplated as the only object worthy of his labors. To these he devoted himself and he became a profound lawyer for the same reason that he was a profound Greek scholar, astronomer and mathematician." If the founders of the courts were in search of learning, Professor Tucker is not wrong in thinking that they found it in Chancellor Wythe. Indeed his learning was so extensive and so lavishly spread upon the pages of his opinions that these opinions appear somewhat pedantic and cumbersome. Not only was legal lore exhausted when he spoke, but the "approved English poets and prose writers"—as he called them—and the more unfamiliar Latin and Greek authors, and even mathematical and natural sciences were quarries from which in concealed places he dug out his allusions and quotations. In the eight pages of one opinion with its footnotes, Bracton and Justinian, Juvenal's Satires, and Quintilian, Euclid, Archimedes and Hiero, hydrostatic experiments and Coke on Littleton, Tristam Shandy and Petronius, Halley and Price and Prometheus, Don Quixote and Swift's Tale of a Tub, Locke's Essay on Human Understanding, and Turkish travellers, chase one another up and down to the bewilderment of all but the universal scholar. All contemporaries stood in awe of his erudition, and referred to him as the famous judge.

His imperviousness to every kind of influence and endeavor to avoid every appearance of evil may be illustrated by two stories told by those who knew him well. A well-to-do former resident of the West Indies, while a case of his was under consideration, sent to the judge's house a bottle of old arrack for the judge and an orange tree for Miss Nelson, his niece. Wythe promptly returned them with thanks, and sent back the message that he had long since given up old arrack and that Miss Nelson had no conservatory in which to plant the orange tree. On another occasion, Bushrod Washington, later Judge Washington of the United States Supreme Court, is said to have brought to Wythe a plea for an injunction to protect a client. The client was a General Blank, who owed money, but had received promise from his creditor that it would not

Page 336

be collected until it suited the convenience of the General. As time elapsed the creditor's patience became exhausted, and he sued for recovery of the debt. General Blank then induced Mr. Washington to draw the papers asking Judge Wythe for an injunction staying judgment on the ground that it was still inconvenient to pay. Wythe calmly examined the papers, and then with a pleasant smile turned to Washington and said: "Do you think I ought to grant this injunction?" Blushing and embarrassed the nephew of Washington replied no, but his client had insisted upon it.

It would hardly be wise in a general article to enter into a detailed consideration of Wythe's decisions, and yet a treatment of the Judge's life that does not at least show the significance of one or two of his important opinions would be too superficial for a serious publication. Interest, however, is added to one of them by the fact that the vital question of jurisprudence involved in the case is one of the mooted questions of our day. We are discussing at length in books and current periodicals the relation of the court to legislative enactments —whether the practice of the courts in declaring null the acts of legislative bodies is historically sound and socially expedient. Whatever may be the social expediency of the doctrine and practice, historical scholars like Professor Beard and Professor McLaughlin have made it clear that John Marshall in 1803 when he handed down the first decision in Marbury vs. Madison declaring null a congressional statute, was not usurping the power; that the course of colonial thought, the position of colonial charters, the Revolutionary conception of the just limitations on English parliamentary authority, the decisions of the state courts after independence was secured, the views of prominent members of the Federal Convention of 1787— all led the way most naturally to the strong position which John Marshall was accused of seizing improperly. Someone with a background of historical knowledge and a broad view of jurisprudence should set forth the Virginia influence operating on the mind of Marshall, especially the views of Marshall's teacher, George Wythe. Not much has been said on this phase of Wythe's importance, and what is said is usually mixed with error and ignorance. It is not true that Wythe

Page 337

was the first state judge to announce the supremacy of state courts over state statutes, but the essential fact is not whether he was first or second, but the vigor with which he announced his opinion, and the influence his views may have had on the mind of his pupil and colleague, the great chief justice, who carried the same conception of judicial supremacy over into the realm of the constitutional law of the nation which Wythe announced in the Virginia courts before which Marshall practiced. The Virginia case which I have in mind is one decided in 1782 by the Court of Appeals, of which Wythe as chancery judge was ex officio member, and over which Edmund Pendleton was presiding justice. It was the case of Commonwealth vs. Caton. The Attorney General of the state was endeavoring to secure the execution of a sentence of treason against Caton and others already convicted but pardoned by an alleged power of the House of Delegates. The issue was presented whether, even if the House in passing their resolution of pardon were within the meaning of the statute, it were not acting beyond its powers, whether the statute itself was not in violation of the constitution of the state, and whether under such circumstances the statute was not void. Pendleton, declaring that the matter was "a deep, important, and tremendous question" the decision of which involved awful consequences, evaded the issue. George Wythe never evaded an issue in his life. He boldly plunged forward in memorable words that cannot be omitted: "I approach the question which has been submitted to us; and although it was said the other day, by one of the judges, that, imitating that great and good man, Lord Hale, he would sooner quit the bench than determine it, I feel no alarm; but will meet the crisis as I ought; and, in the language of my oath of office will decide it, according to the best of my skill and judgment.

"I have heard of an English chancellor who said, and it was nobly said, that it was his duty to protect the rights of the subject against the encroachments of the crown; and that he would do it, at every hazard. But if it was his duty to protect a solitary individual against the rapacity of the sovereign, surely it is equally mine to protect one branch of the legislature, and, consequently, the whole community, against

Page 338

the usurpations of the other and, whenever the proper occasion occurs, I shall feel the duty and fearlessly perform it. Whenever traitors shall be fairly convicted, by the verdict of their peers, before the competent tribunal, if one branch of the legislature, without the concurrence of the other, shall attempt to rescue the offenders from the sentence of the law, I shall not hesitate, sitting in this place, to say to the general court, Fiat justitia, ruat coelum; and to the usurping branch of the legislature, you attempt worse than a vain thing; for, although you cannot succeed, you set an example which may convulse society to its center. Nay more, if the whole legislature, an event to be deprecated, should attempt to overleap its bounds, prescribed to them by the people, I, in administering the public justice of this tribunal will meet their united powers; and, pointing to the constitution, will say, to them, here is the limit of your authority; and hither, shall you go, but no further."

One other case I will just mention and then pass on. During and following the Revolutionary war, acts had been passed in the states attempting to confiscate debts owed by Americans to British creditors—creditors who often had been none too scrupulous themselves in dealings with colonial planters. The legislature of the state passed a statute allowing Virginia debtors owing money to British merchants to pay them by turning into the state treasury paper currency. The treaty of peace, however, in 1783, placed the government of the United States under pledge that no legal impediments would be placed on the collection of American debts due to British citizens. Despite the treaty, payments were withheld. In a case that came before Wythe, regardless of popular clamor, and of the alien character of the claimants, he stepped into the breach, upheld the validity of the treaty and ordered the payment of obligations. In a footnote to this decision added in the report published in 1795, he bitterly scores the idea that a judge should be susceptible of national prejudice, and lashes with the scorpions of his rhetoric attorneys who had advocated the doctrine of theft.

From this slight review of the Chancellor one would, no doubt, acknowledge that Wythe's reputation for boldness,

Page 339

originality, learning, and integrity was well founded. If Marshall was correct in saying that an ignorant, corrupt, and dependent judiciary are the greatest curse that could afflict a people, we should be willing to contend that wise, righteous, and fearless judges, like Wythe, are the most treasured possessions of a free people.

If Wythe was a great statesman and a great judge, to me he is most attractive as a teacher and a man. He was possessed of all the gifts that should adorn the ideal instructor of youth who attempts that sacred office of standing before impressionable minds and characters. In this day, when the teacher's position, the college teacher's position, like that of the clergyman, is being robbed of some of its relative power by the absorption of our generation in the task of the changers of money—when, indeed, the very physical limitations imposed by too meagre financial resources on the teacher in a modern college make impossible to him the utilization of many privileges that adorn and develop the spirit and lend influence to character,—at such a time one re-reads for inspiration the story of a struggling college president like Robert E. Lee of Washington College, and the story of a distinguished statesman and jurist like Wythe, whose chief pleasure was the training of young men. Men like Wythe and Lee have lent a luster to the professor's labors which men like Henry Van Dyke and Woodrow Wilson have tried to keep bright.

Possessed he was of scholarship, of real ingenuity of method, of an inspiring personality, of sincere and solid worth, of a genuine love for his subject, for his profession, and, most important of all, of a deep affection for the young men who ate of the bread of life which he broke. They to him were not receptacles, not apparatus, not material for experimentation, not means of livelihood; they were living souls, they were generous hearted friends, they were companions journeying with him along the road to truth and manliness.

But would we have some facts, names, dates to which we can tie? When Jefferson entered William and Mary College in 1760 he found there as Professor of Mathematics, Dr. William Small, a friend of James Watt, the inventor of the steam engine. After teaching him for two years, Professor Small

Page 340

placed his favorite pupil under the instruction of Wythe, then an eminent lawyer living in Williamsburg. Wythe became to Jefferson his faithful mentor and most affectionate friend and remained such till his death. When Jefferson became in 1779 a member of the Board of Visitors, he reorganized the college and made a distinguished place for his own teacher. In that year the grammar school was dropped, the divinity chairs abandoned, and professorships after the following order were created:

- Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy—James Madison.

- Professor of Medicine and Anatomy—James McClurg.

- Professor of Modem Languages—Charles Bellini.

- Professor of Moral Philosophy, the law of nature and of the nations and the fine arts—Robt. Andrews.

- Professor of Law and Police—George Wythe.

The professorship of law here created and filled by Wythe was, as we have said above, the first in America and the second in the English-speaking world. The professors received each eight hogsheads of tobacco yearly salary, and the students paid 1,000 lbs. of tobacco for the privilege of attending the lectures of two professors, 1,500 to attend any three. It is not without interest that as early as this, old William and Mary, as influential in days gone by as any institution of learning in the country, educator of Presidents of the United States, Governors of Virginia, Justices of the Supreme Courts of the country and the Old Dominion, Senators, Congressmen and other public men without number, boasted of a scientific laboratory, of the honor system in deportment, and of the elective system of study. Thomas Jefferson was the connecting link between William and Mary College and the University, of Virginia.

In his instruction in the law, George Wythe used several methods that are worthy of mention—one was the lecture method. His lecture notes had been preserved as late as 1810. Since then they have disappeared and are probably hid away in an old dust-covered box or barrel in somebody's garret or cellar. Not the least attractive features of his instruction were the expedients used by him to bring out the student's thought

Page 341

and expression. Both the moot court and the moot legislature were used by him, the latter for the purpose of encouraging his students to inform themselves on the questions of the day in Virginia. Would it not be worth while to describe these institutions as they were viewed by a participator in them? Fortunately, one, John Brown, student of William and Mary in 1780, wrote instructive letters from college to his friends, and, fortunately also, these letters are at our hand: "I still continue," he says, "to enjoy my usual state of Health and endeavor to improve by the Advantages of my situation; which of late have been greatly augmented; for Mr. Wythe ever attentive to the improvement of his Pupils, founded two Enstitutions for that purpose, the first is a Moot Court, held monthly or oftener in the place formerly occupied by the Gen'l Court in the Capitol. Mr. Wythe and the other professors sit as Judges, our Audience consists of the most respectable of the Citizens, before whom we plead Causes given out by Mr. Wythe lawyer like I assure you. He has formed us into a Legislative Body, consisting of about 40 members. Mr. Wythe is speaker to the House, and takes all possible pains to instruct us in the Rules of Parliament. We meet every Saturday & take under consideration those Bills drawn up by the Comtee appointed to revise the laws, the [which] we debate and Alter [I will not say amend] with the greatest freedom. I take an active part in both these Institutions & hope thereby to rub off that natural Bashfulness which at present is extremely prejudicial to me. These Exercises serve not only as the best amusement after severe studies, but are very useful & attended with many important advantages."

Would it not be most entertaining and helpful for a modern professor to have a glimpse of the letters that go back home?

If the test of the teacher is the ability and character of the students he turns out into the world and the respect which they retain for him in the more mature years when values in college life are revealed, Wythe must have been one of the greatest of instructors. One of his pupils, as we have seen, became Chief Justice of the United States and followed out the teachings of his preceptor in his own interpretations of the

Page 342

law. Two others, James Monroe and Thomas Jefferson, became President, and another was Henry Clay. The relations between Jefferson and his teacher were a testimony to the greatness of both men. All the tenderness of a tender nature went out from the great Democrat to the mentor of his youth. Letters passed from the distinguished pupil to the old professor that read almost like love letters of affinities. As VicePresident, Jefferson wished the advice of the older man, more than that of any other, in the preparation of the famous "Manual of Parliamentary Law" of which science Wythe had had opportunity to become a master. The Sage of Monticello never failed to speak to others of the character and ability of the professor and the Chancellor. He counted it the highest blessing his nephew could receive to study under the leadership of the same noble spirit who had led him. To him Wythe was "one of the greatest men of his age," the leader of the bar, of spotless virtue. Whoever paid another such homage as this: "I know that, to you, a consciousness of doing good is a luxury ineffable. You have enjoyed it already beyond all human measure." And when Wythe died, he left to his dear and life-long friend, Thomas Jefferson, the best testimony of his love—his library, his mathematical apparatus, his silver cups, and his gold-headed cane.

In his latter days in Richmond we can picture to ourselves an old man of four score years, bald except for the hair rolled up behind his head, of medium height, bowing in men of business and bowing them out without a word, distributing charity through his clerical friends, abstemious in eating and drinking, loving his bath, going himself to his favorite bakery, reading dry papers of the, law with minute conscientiousness—reading them even on that premature bed of death, to which he was doomed by the poisonous hand of a grand-nephew,*—breathing out words of charity and faith.

On the day of the funeral, the 10th of June, 1806, there followed the remains, clergymen, physicians, city councillors, the governor, besides relatives and friends, and a numerous company of citizens, more numerous than would have attended, say those who were present, the body of any other Virginian

- * It should be said that the grand-nephew was not judicially convicted.

Page 343

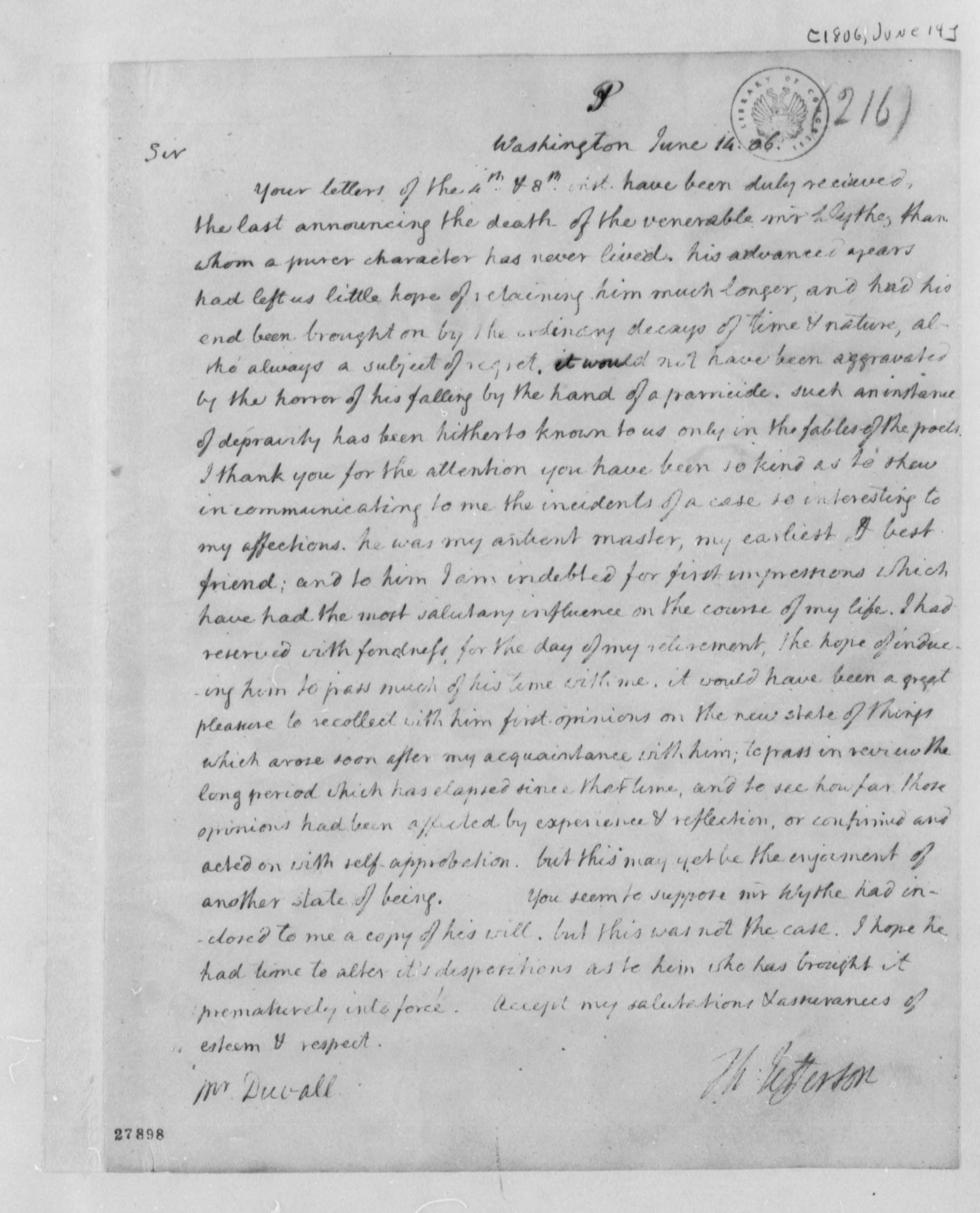

- Main article: Jefferson-DuVal Correspondence

of the time. The funeral oration was delivered in eloquent terms by a pupil whom Wythe had cared for in a peculiarly intimate manner, William Munford, member of the Governor's Council. And Thomas Jefferson, President of the United States, wrote to William DuVal of Richmond, neighbor and executor of Wythe, the following letter hitherto unpublished:

Washington June 14, 06.

SIR

Your letters of the 4th & 8th inst. have been duly received, the last announcing the death of the venerable Mr. Wythe, than whom a purer character has never lived—his advanced years had left us little hope of retaining him much longer, and had his end been brought on by the ordinary decays of time & nature, altho' always a subject of regret, it would not have been aggravated by the horror of his falling by the hand of a parricide—such an instance of depravity has been hitherto known to us only in the fables of the poets—I thank you for the attention you have been so kind as to shew in communicating to me the incidents of a case so interesting to my affections, he was my antient master, my earliest & best friend; and to him I am indebted for first impressions which have had the most salutary influence on the course of my life. I had reserved with fondness, for the day of my retirement, the hope of inducing him to pass much of his time with me. it would have been a great pleasure to recollect with him first opinions on the new state of things which arose soon after my acquaintance with him; to pass in review the long period which has elapsed since that time, and to see how far those opinions had been affected by experience & reflection, or confirmed and acted on with self-approbation, but this may yet be the enjoiment of another state of being.

You seem to suppose mr Wythe had inclosed to me a copy of his will, but this was not the case. I hope he had time to alter it's dispositions as to him who has brought it prematurely into force. Accept my salutations & assurances of esteem and respect.

TH: JEFFERSON.

Mr. Duvall

See also

References

- ↑ Dice Robins Anderson, "The Teacher of Jefferson and Marshall," Southern Atlantic Quarterly 15, no. 4 (October 1916), 327-343.

- ↑ Robert S. Alley, "Anderson, Dice Robins," in Dictionary of Virginia Biography, vol. 1, eds. John T. Kneebone, J. Jefferson Looney, Brent Tarter, and Sandra Gioia Treadway (Richmond, VA: Library of Virginia, 1998), 130-131.

- ↑ "Commencement Speakers," Special Collections Research Center Wiki, Swem Library.

External links

- Read this article in Google Books.