Difference between revisions of "Turpin v. Turpin"

(→Works Cited or Referenced by Wythe) |

(→Works Cited or Referenced by Wythe) |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

Citation in Wythe's opinion: | Citation in Wythe's opinion: | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| − | <tt><span style="color: #006600;"> Swinburne (part III. § VI. no.17.) <ref>Wythe 140.</ref> | + | <tt><span style="color: #006600;"> Swinburne (part III. § VI. no.17.) </span></tt> <ref>Wythe 140.</ref> </blockquote> |

===Justinian's ''Digest''=== | ===Justinian's ''Digest''=== | ||

Revision as of 14:11, 12 November 2015

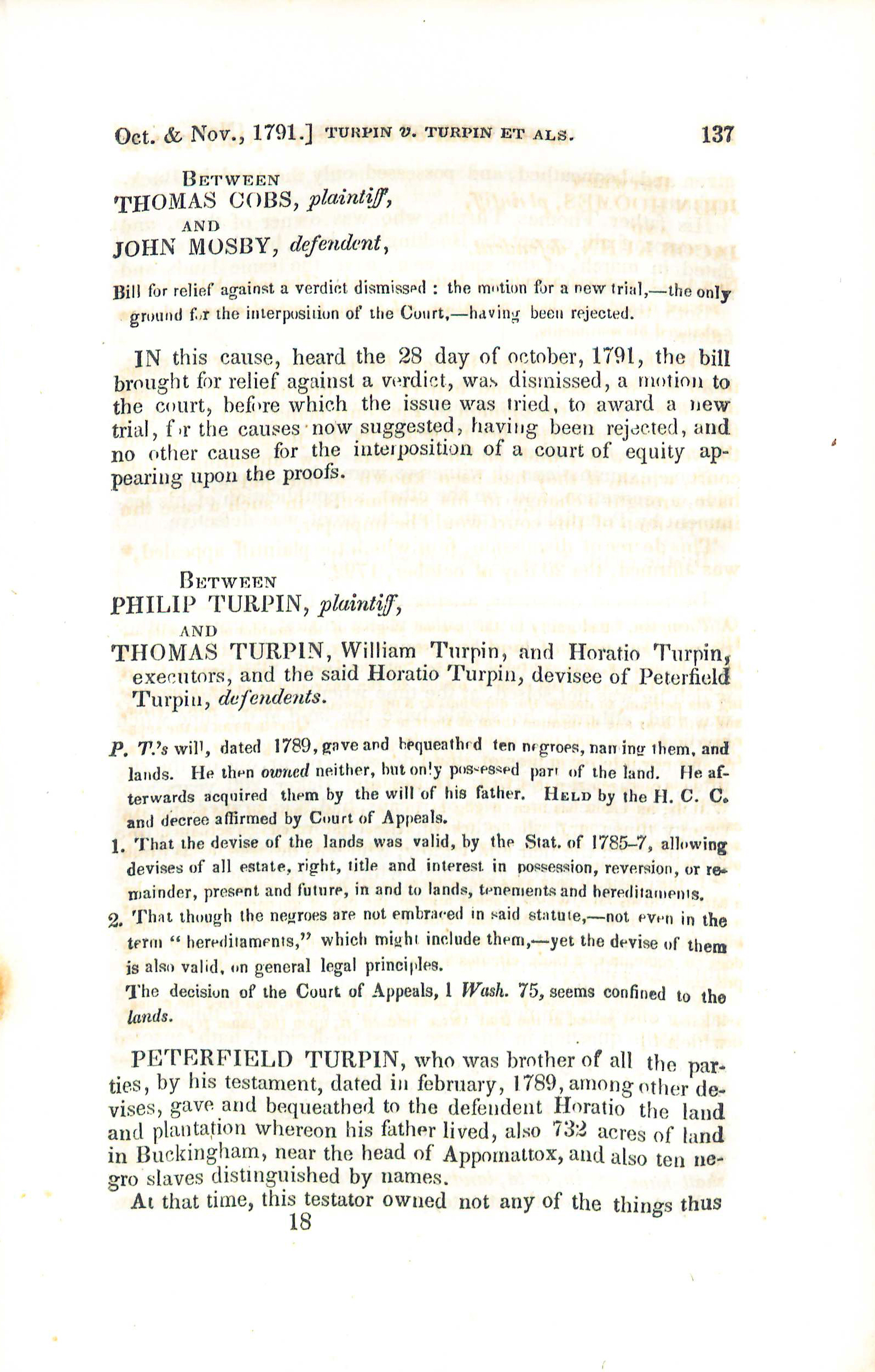

Turpin v. Turpin, Wythe 137 (1791),[1] discussed whether a person could give away land and chattel in a will that the person did not own at the time they wrote it but did own when they died.

Background

In February 1789, Peterfield Turpin created a will[2] giving his brother Horatio the land and plantation where Peterfield's father Thomas lived plus ten slaves. Peterfield's will also gave Horatio 732 acres of land in Buckingham County. When Peterfield wrote the will, he did not own any of these.

Thomas Turpin owned everything listed in Peterfield's will. In March 1789, Thomas created a will giving the slaves, the land and plantation where Thomas lived, and the land in Buckingham County to Peterfield.

Thomas died before Peterfield, who died some time before the High Court of Chancery's decision.

Philip Turpin, the plaintiff, was another of Peterfield's brothers. Philip claimed that Peterfield's will did not control who inherited the land in Buckingham County, the slaves, or the land and plantation where Thomas lived because Peterfield did not own any of those when Peterfield wrote his will. Therefore, as a common-law heir to Peterfield, Philip argued he was entitled to a share and filed a bill with the High Court of Chancery to claim it.

The Court's Decision

The High Court of Chancery dismissed Philip's bill.

Wythe stated that under English common and statutory law a will that awarded land which the testator (i.e., the person who wrote the will) did not own when they created it was void, even if the testator owned the land when they died. Wythe cited to Butler and Baker's Case as found in Coke's Reports[3], as well as Bunker v. Cook, as discussed in Gilbert's Law of Devises, Revocations, and Last Wills.[4]

Wythe noted, however, that a 1785 Virginia statute changed the law so that a person twenty-one years or older (who was not a married woman) could award land in a will whether they owned that land at the time they created the will or at the time they died.[5] The question then became what exactly did Peterfield do when he wrote the will giving the land and slaves to Horatio?

If Peterfield was giving Horatio the rights to the property Peterfield had at the time the will was created, then the award was void, unless - as Roman civil law allowed - the will also bound the executor of Peterfield's estate to use the estate's proceeds to purchase the land Peterfield did not own in order to give it to Horatio. Here, Wythe referred to Justinian's Institutes[6] and Code[7], which said that a person could bequeath another's property to an heir. Wythe did not mention it, but these two sections of the Corpus Juris Civilis added that a person could only bequeath another's property if they knew it belonged to someone else. If the person genuinely thought they owned the property, they could only bequeath the property to a very close relation - the idea being that the person would still have bequeathed the property to that heir had they known they did not really own it.

Reasoning that the law prefers to interpret wills in a way that keeps them valid, Wythe chose to read Peterfield's words as giving Horatio a future interest in the land; i.e., Horatio would get whatever interest in the described land Peterfield had when Peterfield died. By this reading, Peterfield's award to Horatio of the land in Buckingham County and the land where Thomas lived were valid.

The 1785 Virginia statute only discussed bequeathing land, though, so Wythe proceeded to the next question: did Peterfield make a valid award of ten named slaves to Horatio, even though Peterfield did not own those slaves when he wrote the will?

Wythe began by looking at Swinburne's Treatise of Testaments and Last Wills. Swinburne states that under English law, if the testator awards a specific thing in the will that the testator did not own at the time, but later bought the specific item, the presumption is that the testator bought to item to give to the heir, and the award is valid. If the testator only made a general award (e.g., "I give all my land to X"), however, any land purchased after the will's creation is not part of the award to the heir. Swinburne cited Cato's Rule,[8] which said that "any legacy that would be void if the testator died immediately after making his will will not be valid no matter how long afterwards he may die," as his source for civil law. Wythe, however, found Cato's Rule inappropriate for circumstances that did not involve some sort of defect in the testator's ability to properly consent.

Swinburne cited the case of Brett v. Rigden[9] to support his contention in English common law. Wythe distinguished Brett on the facts, because it involved an award of land, but also said that it was not binding precedent. Wythe stated that in Bunker v. Cook, Chief Justices Holt and Trevor declared Brett invalid precedent. In Bunker, Chief Justice Holt cited two more English cases, Ashby v. Laver[10] and Southward v. Millard[11], but Wythe distinguished those cases on the facts from the present situation.

Since Wythe found no caselaw precedent on point, he proceeded to answer the question by deducing it from legal principles. If a bequest were a present-day award of the right to own something, then Peterfield's gift of the slaves in his will would be invalid, because he did not own the slaves when he wrote the will. A bequest, however, is not a present-day gift of rights; it merely appoints the person the testator wants to succeed him in holding the rights to something after the testator's death. Wythe noted that Roman law allowed a testator to bequeath something he did not own at the time he wrote the will[12], and that the countries which based their contemporary laws on Roman civil foundations still observed this rule. Furthermore, the fact that Peterfield did not alter his will after he became the slaves' owner affirmed his desire that Horatio own the slaves after Peterfield died.

Wythe also noted that the law usually allows a testator to make a general award of chattel to be acquired after writing the will to avoid the inconvenience of rewriting it every time the testator acquires something new. The testator's power to gift is the same, however, whether making a general award of chattel or an award of specifically-described chattel; to require the testator to republish the will just because he specifically described the chattel seemed to Wythe a nonsensical distinction.

Therefore, Wythe concluded, the devise in Peterfield's will giving ten named slaves to Horatio was also valid.

Philip appealed to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, which affirmed the Chancery Court's decision.[13]

Works Cited or Referenced by Wythe

Henry Swinburne's A Treatise of Testaments and Last Wills, compiled out of the Laws Eccelesiastical, Civil and Canon, as out of the Common Laws,...

Citation in Wythe's opinion:

Swinburne (part III. § VI. no.17.) [14]

Justinian's Digest

Quotation in Wythe's opinion:

...is this quod, si testamenti facti tempore decessisset testator, inutile foret, id legatum quandocumque decesserit, non valet. Translation: That which would be invalid if a testator has died at time of his will being made, will be invalid whenever he will have relinquished that legacy.[15]

For this quote, Wythe most likely used his copy of the Corpus Juris Civilis which includes the Digest of Justinian.

Edmund Plowden's Les Commentaries, ou Reportes de Edmunde Plowden…

Citation in Wythe's opinion:

"The quotation from Plowden's Commentaries is appositive to the principal case..."

Justinian's Codex

Citation in Wythe's opinion:

<tt>VI. tit. XXXVII. l. 10.</tt> Text of Citation: When anyone knowingly bequeaths property which belongs to another, whether it be a legacy or has been left under a trust, it can be claimed by him who has a right to it under either of these titles. If, however, when the testator bequeathed it, he believed it to be his own, the bequest will not be valid unless it was left to a near relative, to his wife, or to some other such person; and this will be the case even if he was aware that the property did not belong to him.[16]Justinian's Institutes

Citation in Wythe's opinion:

<tt>II. tit. XX §4.</tt> Text of Citation: A legacy may be given not only of things belonging to the testator or heir, but also of things belonging to a third person, the heir being bound by the will to buy and deliver them to the legatee, or to give him their value if the owner is unwilling to sell them. If the thing given be one of those of which private ownership is impossible, such, for instance, as the Campus Martius, a basilica, a church, or a thing devoted to public use, not even its value can be claimed, for the legacy is void. In saying that a thing belonging to a third person may be given as a legacy we must be understood to mean that this may be done if the deceased knew that it belonged to a third person, and not if he was ignorant of this: for perhaps he would never have given the legacy if he had known that the thing belonged neither to him nor to the heir, and there is a rescript of the Emperor Pius to this effect. It is also the better opinion that the plaintiff, that is the legatee, must prove that the deceased knew he was giving as a legacy a thing which was not his own, rather than that the heir must prove the contradictory: for the general rule of law is that the burden of proof lies on the plaintiff.[17]References

- ↑ George Wythe, Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852), 137.

- ↑ In this case, Wythe usually refers to a "testament". There was a distinction between a will and a testament in Wythe's time; Jacob's New Law-Dictionary said that a will gives away land, while a testament only gave away goods and chattel. Giles Jacob, "Will, or Last Will and Testament", A New Law-Dictionary ([London] In the Savoy: Printed by E. and R. Nutt, and R. Gosling, (assigns of E. Sayer, Esq.) for J. and J. Knapton et al., 1729). Wythe seemed to use the term "testament" for both types of documents, though, and the terms are interchangeable for modern-day audiences, often found together, so this article will use the term "will" to refer to both types of documents. Interestingly, Bouvier's Law Dictionary said that the "will" was a concept restricted to the common law, while the term "testament" was only found in the field of Roman civil law. John Bouvier, rev. by Francis Rawle, "Will", Bouvier's Law Dictionary (Kansas City, MO: Vernon Law Book Co., 8th ed. 1914). Perhaps Wythe preferred to use the civil law concept of the testament rather than voice the English common-law concept of the "will"?

- ↑ 76 Eng. Rep. 684, 3 Co. Rep. 25a (1591).

- ↑ 1 Sir Geoffrey Gilbert, The Law of Devises, Last Wills, and Revocations 126 (4th ed. 1792). The case is also covered in 1 Eng. Rep. 1149, 1 Salk. 237 (1707), but Gilbert's report of the decision is much more detailed and includes the arguments made in the case.

- ↑ 1785 Laws of Virginia, Ch. 61, 12 Hening 140.

- ↑ Justinian Inst. 2.20.4

- ↑ Justinian Code 6.37.10

- ↑ "Catoniana regula sic definit, quod, si testamenti facti tempore decessisset testator, inutile foret, id legatum quandocumque decesserit, non valere. quae definitio in quibusdam falsa est." Justinian Digest 34.7.1.

- ↑ 75 Eng. Rep. 516, 1 Plowden 340

- ↑ 75 Eng. Rep. 1017, Goldesborough 93.

- ↑ 82 Eng. Rep. 445, March, N.R. 135.

- ↑ Justinian Inst. 2.20.4, Justinian Code 6.37.10

- ↑ Turpin v. Turpin, 1 Va. (1 Wash.) 75 (1791).

- ↑ Wythe 140.

- ↑ Wythe 141.

- ↑ Wythe 139. Translation: S.P. Scott.

- ↑ Wythe 139. Translation: J.B. Moyle.