Difference between revisions of "Hustings Court Minutes"

(→See also) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div style="float: left; margin: 0 30px 20px 0;">__TOC__</div> | <div style="float: left; margin: 0 30px 20px 0;">__TOC__</div> | ||

| − | These pages from a Virginia Hustings Court Minute Book detail the charges of | + | These pages from a [[Media:HustingsCourtMinutesBookNo3June1806.pdf|Virginia Hustings Court Minute Book]] for the Richmond, Virginia from June, 1806 detail the charges of forgery and murder against [[George Wythe Sweeney]] and supporting evidence in the form of testimony before the court.<ref>[[Media:HustingsCourtMinutesBookNo3June1806.pdf|Virginia Hustings Court Minute Book No. 3]] (1802-1806), Richmond, Virginia. Microfilm at the [http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/local/results_all.asp?CountyID=VA760#COURT Library of Virginia].</ref> |

| + | |||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:HustingsCourtMinutesBookNo32June1806.jpg|thumb|right|400px|<p>Page for June 2, 1806 from the Richmond, Virginia Hustings Court Minute Book, showing evidence and testimony for the trial of [[George Wythe Sweeney]] for forgery and murder:</p><p>"At a Court of Hustings call'd and held for the City of Richmond at the Courthouse on Monday, the 2nd day of June, 1806 for the examination of Geo. W. Swinney, charged with having forged 6 checks on the Bank of Virginia in the name of Geo. Wythe, Esq. and drawing from the said Bank by virtue thereof two hundred and fifty dollars to his own use."]] | ||

Hustings Courts, named after similar courts in England,<ref>George Lewis Chumbley, ''Colonial Justice in Virginia: The Development of a Judicial System, Typical Laws and Cases of the Period'' (Richmond: The Dietz Press, 1938), 77.</ref> were a system of courts unique to eighteenth and nineteenth century Virginia.<ref>John P. Alcock, "[http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~jcat2/18centvalaw.html 18th Century Virginia Law]," Presentation at the Library of Virginia, November 17, 1999.</ref> They administered to independent cities, serving as the equivalent of county courts, adjudicating matters of lands and chattels, debts, and contracts.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Hustings Courts also had a probate division for the administration of wills. The courts heard minor civil matters from their locality, passing major disputes on to the General Courts.<ref>Ibid.</ref> The Hustings Courts also heard local criminal matters that did not involve potential penalties to life or body parts. In criminal cases involving such punishments, the Hustings Court acted as a grand jury, determining whether or not to indict the alleged offender. If the Hustings Court determined that the offender should be indicted, it was responsible for bonding the offender and any witnesses to appear at the next available session of the District Court.<ref>W. Edwin Hemphill, "Examinations of George Wythe Swinney for Forgery and Murder: A Documentary Essay," in Julian P. Boyd and W. Edwin Hemphill, ''The Murder of George Wythe: Two Essays'' (Williamsburg, Va.: The Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1955), 40.</ref> This function is illustrated by the transcripts of the Hustings Court at Richmond below, which recorded the twin indictments of George Wythe Swinney for fraud and murder. At the beginning of each transcript, the court notes the indictment. After testimony, it bonds the witnesses to appear at the next District Court session, lest they forfeit the property specified. | Hustings Courts, named after similar courts in England,<ref>George Lewis Chumbley, ''Colonial Justice in Virginia: The Development of a Judicial System, Typical Laws and Cases of the Period'' (Richmond: The Dietz Press, 1938), 77.</ref> were a system of courts unique to eighteenth and nineteenth century Virginia.<ref>John P. Alcock, "[http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~jcat2/18centvalaw.html 18th Century Virginia Law]," Presentation at the Library of Virginia, November 17, 1999.</ref> They administered to independent cities, serving as the equivalent of county courts, adjudicating matters of lands and chattels, debts, and contracts.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Hustings Courts also had a probate division for the administration of wills. The courts heard minor civil matters from their locality, passing major disputes on to the General Courts.<ref>Ibid.</ref> The Hustings Courts also heard local criminal matters that did not involve potential penalties to life or body parts. In criminal cases involving such punishments, the Hustings Court acted as a grand jury, determining whether or not to indict the alleged offender. If the Hustings Court determined that the offender should be indicted, it was responsible for bonding the offender and any witnesses to appear at the next available session of the District Court.<ref>W. Edwin Hemphill, "Examinations of George Wythe Swinney for Forgery and Murder: A Documentary Essay," in Julian P. Boyd and W. Edwin Hemphill, ''The Murder of George Wythe: Two Essays'' (Williamsburg, Va.: The Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1955), 40.</ref> This function is illustrated by the transcripts of the Hustings Court at Richmond below, which recorded the twin indictments of George Wythe Swinney for fraud and murder. At the beginning of each transcript, the court notes the indictment. After testimony, it bonds the witnesses to appear at the next District Court session, lest they forfeit the property specified. | ||

| Line 14: | Line 17: | ||

====Page 1==== | ====Page 1==== | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| − | At a Court of Hustings | + | At a Court of Hustings call'd and held for the City of Richmond at the Courthouse on Monday, the 2nd day of June, 1806 for the <s>brief</s> examination of Geo. W. Swinney, charged with having forged 6 checks on the Bank of Virginia in the name of Geo. Wythe, Esq. and drawing from the said Bank by virtue thereof two hundred and fifty dollars to his own use. |

Present: Edw’d Carrington – Mayor | Present: Edw’d Carrington – Mayor | ||

Revision as of 12:58, 23 September 2015

These pages from a Virginia Hustings Court Minute Book for the Richmond, Virginia from June, 1806 detail the charges of forgery and murder against George Wythe Sweeney and supporting evidence in the form of testimony before the court.[1]

Background

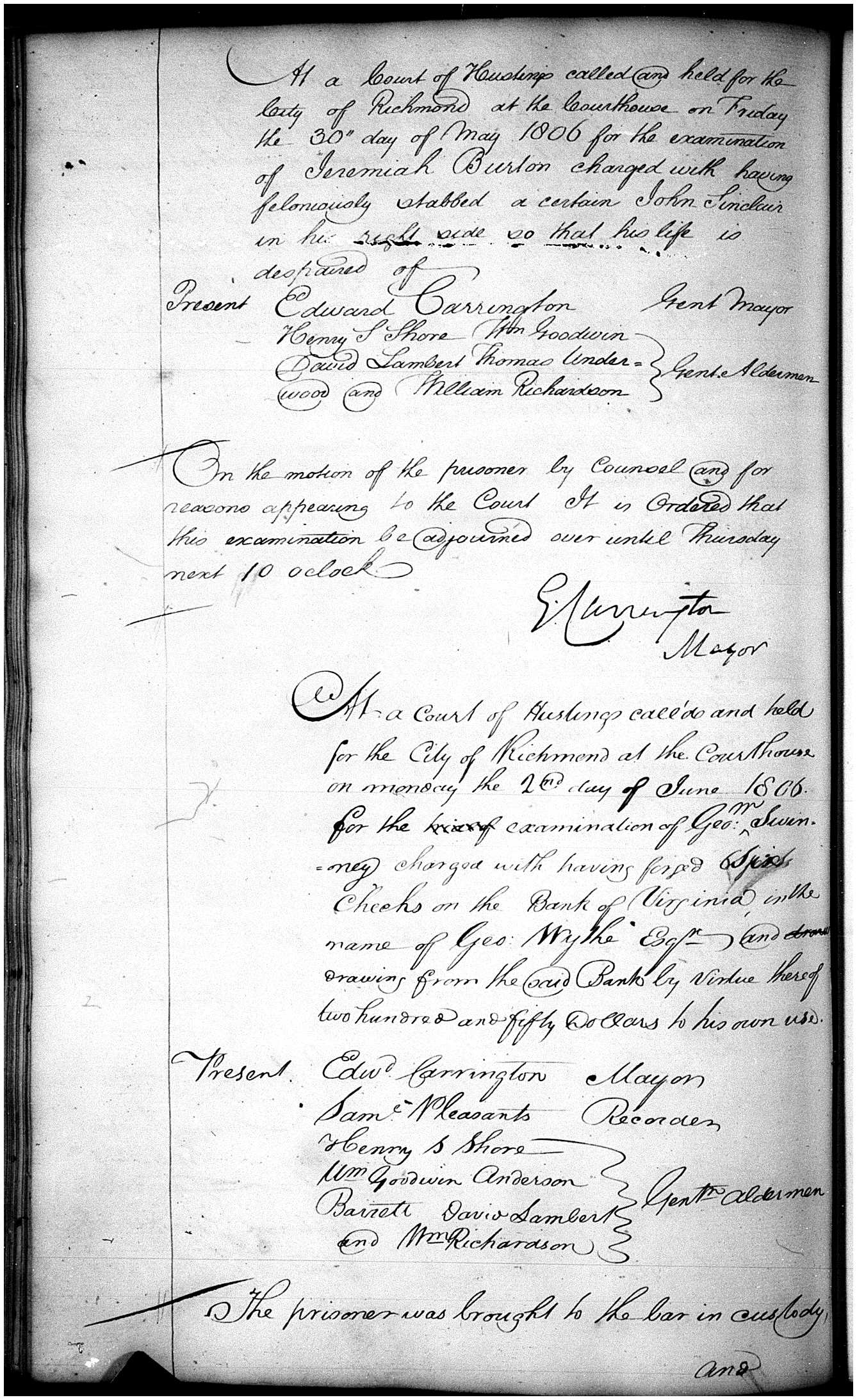

Page for June 2, 1806 from the Richmond, Virginia Hustings Court Minute Book, showing evidence and testimony for the trial of George Wythe Sweeney for forgery and murder:

"At a Court of Hustings call'd and held for the City of Richmond at the Courthouse on Monday, the 2nd day of June, 1806 for the examination of Geo. W. Swinney, charged with having forged 6 checks on the Bank of Virginia in the name of Geo. Wythe, Esq. and drawing from the said Bank by virtue thereof two hundred and fifty dollars to his own use."

Hustings Courts, named after similar courts in England,[2] were a system of courts unique to eighteenth and nineteenth century Virginia.[3] They administered to independent cities, serving as the equivalent of county courts, adjudicating matters of lands and chattels, debts, and contracts.[4] Hustings Courts also had a probate division for the administration of wills. The courts heard minor civil matters from their locality, passing major disputes on to the General Courts.[5] The Hustings Courts also heard local criminal matters that did not involve potential penalties to life or body parts. In criminal cases involving such punishments, the Hustings Court acted as a grand jury, determining whether or not to indict the alleged offender. If the Hustings Court determined that the offender should be indicted, it was responsible for bonding the offender and any witnesses to appear at the next available session of the District Court.[6] This function is illustrated by the transcripts of the Hustings Court at Richmond below, which recorded the twin indictments of George Wythe Swinney for fraud and murder. At the beginning of each transcript, the court notes the indictment. After testimony, it bonds the witnesses to appear at the next District Court session, lest they forfeit the property specified.

Hustings Courts also had some ancillary duties. A Hustings Court could appoint a guardian for an orphan, or bind an “orphan of small estate” out (make the orphan an indentured servant).[7] The courts could also prescribe local liquor prices, seat juries that would recommend the location of new public works, commission the construction of infrastructure, suggest officials to be appointed by the Governor, and appoint local law enforcement personnel.[8] The Hustings Court also admitted local attorneys to the bar. In essence, a Hustings Court fulfilled local judicial duties, served as a support structure to General Courts in the state, and served an administrative role in their localities.

Hustings Courts were abolished in 1850, replaced either by the General Courts or by corporation courts, which in turn were abolished in 1973 and replaced with general circuit courts.[9]

This specific Hustings Court document contains testimony regarding the indictments for fraud and murder against George Wythe Sweeney, George Wythe's grand-nephew. These "minutes" detail the unofficial record of proceedings in the Hustings Court, and were transcribed later in the official Order Book.[10]

Document text

June 2nd

Page 1

At a Court of Hustings call'd and held for the City of Richmond at the Courthouse on Monday, the 2nd day of June, 1806 for the

briefexamination of Geo. W. Swinney, charged with having forged 6 checks on the Bank of Virginia in the name of Geo. Wythe, Esq. and drawing from the said Bank by virtue thereof two hundred and fifty dollars to his own use.Present: Edw’d Carrington – Mayor

Sam Pleasants – Recorder

Henry S. Shore, Wm. Goodwin, Anderson Barrett, David Lambert, and Wm. Richardson – Gentleman Aldermen

The prisoner was brought to the bar in custody and

Page 2

and there upon sundry witnesses being sworn and exam’d, and the prisoner in his defence fully heard: On consideration whereof it is the opinion of the Court that the prisoner is guilty of the charge aforesaid, and for the same that he undergo a trial at the District Court to be holden at the Capitol in this city in September Court. And being in the opinion of the Court bailible, it is ordered that he enter into a recognizance with good security in sum of $1000 for his appearance there on the first day of the Court to answer an indictment for the same (which may be done before a single magistrate) and failing herein he is remanded to jail until discharge by due course of law. Wm. Dandridge, Teller of the Bank, depos’d that on Tuesday last the prisoner produced to him at the Bank a check thereon for $100 drawn in the name of Geo. Wythe, Esq. which he paid; that some time after in examining the check he suspected it to be a forged one and accordingly went to the prisoner and stated (crossed out) that he believe [sic] there was a mistake, who thereupon produced the money to the deponent which he took. The prisoner frequently applied with checks at the bank in the name of the said Geo. Wythe and (smudge) the deponent believes that six now produced in court were produced by him (the prisoner) and are counterfeit. Peter Tinsley depos’d that he carried seven checks (among which is the one above spoken of) to the (illegible) Geo. Wythe, who denied that any but one of them had been drawn or signed by him.

Page 3

Wm. Dandridge and Peter Tinsley bound in £100 each to appear at the next District Court against the prisoner. -- E. Carrington: Mayor

June 23rd

Page 1

At a Court of Hustings called and held for the City of Richmond at the Courthouse on Monday the 23rd day of June1806 for the (trial crossed out) examination of Geo. W. Swinney, charged with murder.

Present: Edw’d Carrington – Mayor Samuel Pleasants – Recorder Henry S. Shore, Anderson Barret, and Wm. Richardson – Gentleman Alder’n

The prisoner was led to the bar in custody, and thereupon sundry witnesses being sworn and examined, and the prisoner and his defence heard: On consideration whereof it is the opinion of this Court that he is guilty of the charge aforesaid and that for the same he undergo a trial at the next District Court to be held at the Capitol in this laity in the month of Sept. next and thereupon he is remanded to jail for that purpose. The testimony on behalf of the Commonwealth is annexed to the (to the is repeated and crossed out) next page and made a part of the record. Drs. McClurg, Foushee and McCaw [sic] and Wm. Rose, Samuel McCraw, Fleming Russell, Wm. Claiborne, William Price (Register), Nelson, Abbott, Taylor Williams bound in £100 ea. to appear at the District Ct. to give evidence on behalf of the Comm’th and prisoner. -- E. Carrington: Mayor

Page 2

[Page contains the testimony mentioned in the above transcription]

Tarlton Webb: About a fortnight or three weeks before Geo. Swinney was committed to jail, Swinney had enquired where he could procure any Ratsbane. Webb observed that it was against the law of the United States to have it. The day before Swinney was apprehended, he came to the mother of the deponent and shewed the deponent some drug wrapped in paper, which he said was ratsbane and informed him that he intended to kill himself and offered to give him the deponent some if he wanted to die. The deponent, being shown the drug found at the jail and produced by Wm. Rose, deposes that what thw prisoner shew’d him was like that in Wm. Rose’s possession and that there was about one table spoonful. The prisoner stated to the deponent that he was very unhappy and something press’d against his mind, but altho applied to, would not disclose the cause of his uneasiness to the deponent.

William Rose: His servant girl, Pleasant, went to his garden about 12 o’clock the day after the prisoner was committed to jail and brought the paper this day produced which the deponent immediately knew to by arsenic. When the prisoner was committed, the deponent did not search him but one hour and a half or there about hearing that that it was probable he had pistols, he went into the jail and felt his pocket and felt a heavy substance wrapped in paper, but supposing that it might be coppers or some few eighteen penny pieces, he did not take it out of his pocket. The prisoner had the use of the debtors room and the jail yard at his option. As soon as arsenic found suspected Mr. Wythe was poisoned.

Page 3

Samuel McCraw: Being informed by Mr. Rose that Arsenic had been found in his garden proposed to have the servant carried into the garden to see the place where found, to ascertain whether deposited there or thrown from the jailyard. That at the place where the serv’t stated the arsenic found, he found two papers laying about eighteen inches apart. That the crude arsenic had penetrated a little into the earth there were now plants, one a fennel, the other a beat [sic] broke off as he supposed by throwing the arsenic over the jail wall. That he thinks it must have come from the jail yard. The beat that was wounded was next the jail wall and was wounded considerably farther from the groud than the fennel. On the first of June, one week after Mr. Wythe’s attack, he was requested to go to attest Mr. Wythe’s will. Mr. Wyhte requested Swinney’s room and desk be searched. He, with others, was conducted (requested was crossed out before it) to the room where Swinney lodged, opened the chest, and found a portfolio with a qr. of blotting paper which the deponent believes to be of the same ream with what was found wrapped around the arsenic found in the garden. In Swinney’s room on a writing table he found a paper on which was half a dozen strawbwerries, with the appearance of arsenic having been sprinkled over them. He found a phial with an appearance of having had a liquid, some of which adhered to the side of the phial, and on examination was believed to have been a mixture of arsenic and sulphur. He also found two pieces of coarse brown paper with something adhering to each, which was also declared to be arsenic and sulphur. The deponent frequently visited Mr. Wythe in his last illness and he appeared to be in great agony from the first of it to his death. Some time before the death of Mr. Wythe while sitting by him, Mr. Wythe exclaimed “cut me”. The deponent supposed he wanted to have his flannel cut loose, which the deponent

Page 4

accordingly did, which gave apparent displeasure to Mr. Wythe, who then put his hand to his throat and heart and again called out, “cut me,” but could make no further explanation. This induced a belief in the deponent and those present that it was his wish to be opened after his death. The deponent never did hear Mr. Wythe express any suspicion of having been poisoned.

Mr. Russell: The day he rec’d the warrant he went to Mr. Wythe’s and found Mr. Swinney. When he shewed the prisoner the warrant and carried him to Maj. Duval’s and discovered he had no pistols, took his knife from him and put his hand in his coat pocket and felt very distinctly that he had two separate parcels of something wrapped in paper in his pocket, and made no further search after committed to jail. The deponent informed Mr. Rose he had something else in his coat pocket and advised him to make a search but did not go with Mr. Rose to make it.

Mr. Taylor Williams: About 3 weeks before the prisoner was apprehended, Swinney mentioned something to hi, about poison. The deponent informed him that copperas and water was poison. In about six or seven days after the prisoner began a conversation with the witness about poison, the deponent then told him ratsbane was poison and that a gentleman of his acquaintance used it for the purpose of killing rats and that it was to be bought in the shops, but does not recall with certainty whether Swinney asked him where to be had.

Page 5

Maj. Duval, on 26th May went to see Mr. Wythe, did not know he was sick, found him very ill, extended on his back. [He] said he had not caught cold, that he was as well as usual in the morning, and eat his breakfast as usual but immediately taken extremely ill, confined to his back except when forced up, which was upwards of forty times, and had 15 large evacuations. After he was committed for the forgery, [he] applied by letter to the deponent to be bailed. Wythe would have nothing to do with bailing. Mr. Wythe said he was taken ill on the 26th May, about nine o’clock after having ate his breakfast; that on Wednesday or Thursday after Swinney was apprehended, Mr. Wythe requested that Swinney’s room and trunk might be searched, which he repeated frequently and finally on the 1st June prevailed on McCraw and some others, who searched the room and found some paper with something adhering to it, which was concluded by Dr. Greenhow to be arsenic. The deponent saw the appearance of arsenic in an outhouse of Mr. Wythe’s, in his yard, used as a shop; and that some also found in an old smoak house on a wheelbarrow, which on being tried with a pin was proved to be arsenic. On Thursday before Mr. Wythe’s death he made an ejaculation and declared he was murdered in a low tone of voice.

Generally believed that Mr. Wythe had left Mr. Swinney a great portion of his Estate and known that he had made some provision for the Mulatto boy, Brown.

Page 6

Mr. Sam’l Greenhow gave the same evidence upon the search of Swinney’s room and trunk with [blank]. Wm. Price: same evidence as McCraw and Greenhow on the subject of the search of Swinney’s room and of Mr. McCraw on the request of Mr. Wythe to be cut. Mr. McCraw mentioned at that time that he supposed Mr. W wanted to be cut open. Mr. Wythe appeared to be in great agony during his illness, more particularly when moved. Nelson Abbot says that on Saturday 24th May last he put an axe, now produced, into a shop in Mr. Wythe’s yard that he had lent him for a workshop; that on the 27th he went to Hanover and returned on Friday the 30th when he discovered the arsenic in its present situation and a hammer which stained with yellow, which has since been cleaned. The negroes in the shop said the prisoner had beat something (they did not know what) on the side of the axe with the hammer.

William Claiborne: Went to Mr. Wythe’s the Wednesday after [Mr. Wythe is crossed out] his illness, who informed him that on the Sunday preceding in the morning, he was as well as usual, immediately after breakfast taken with a colarimorbus and then a violent lax, went forty times that day and had at least fifteen large evacuations; that on Saturday night he supped on milk and strawberries; Mr. Wythe said all the negroes taken at the same time; went into the kitchen and found most of them very ill; went to Maj. Duval’s and expressed the opinion that the family were poisoned, and suspected the prisoner in consequence of his having been detected in the forgery, as the death of Mr. Wythe before his detection could only prevent an alteration in his will which the deponent believed was much in favor of the prisoner. The deponent frequently told the prisoner that he would be well provided

Page 7

for by Mr. Wythe if he behaved well; after the death of the yellow boy, told by some of the negroes that arsenic was found in the out houses; the witness took some off the wheelbarrow in the old smoke house; that he applied fire to it and found from the smell it was arsenic; the deponent asked Mr. Wythe whether the prisoner breakfasted with him the morning before he was taken. At first he did not answer, directly afterwards said he did not know, he was always called to his breakfast but sometimes took nothing to eat or drink. [Claiborne] observed he died in peace with all the world, Mr. Wythe said he had or should leave directions for his executor to search Swinney’s trunk. This took place after death of the boy Michael, about sunset on the first of June.

Mr. E. Randolph Sunday, 1st June about 9 o’clock Maj. Duval informed deponent of the death of Brown from poison and Mr. Wythe as probably dying from the same. Mr. Wythe told him he had supped on strawberries and milk the Saturday before he was taken ill and wished his will to be altered so as to give to the prisoner’s brothers and sisters what he had given him. [Randolph] made the alteration, then returned home and afterwards returned and informed Mr. Wythe of the death of Michael Brown. The former codicil to the will destroyed, and a new one made. On Wednesday 4th June, informed by old Lydia that more marks of poison […] went into the shop and saw Abbot’s axe. The negro was uncertain whether the 24th day of May or the 26th that Swinney had caused the appearance but at last settled that it was on Saturday when he found the prisoner in the shop and one of the doors forced, and the prisoner in the act of pounding something on the axe. The prisoner asked him what it was, the negro replied he believed it was ratsbane. The prisoner then scraped it as clean as he could off the axe and folded it up in a piece of paper, wiped the axe with shavings. – generally understood and believed that Mr. Wythe had left the bulk of his estate to the

Page 8

prisoner.

Doctor McClurg Present at the opening of the body of Michael Brown. The lower part of the stomach very much inflamed, had the appearance of black vomit, all very much inflamed. Went to visit Mr. Wythe on the day before the boy died, found him with a fever, tounge very foul, had had no passage for 12 hours and was free from pain. The appearance of the boy was such as arsenic might have produced, but such as might also have been produced by a great collection of bile. He was present at the opening of Mr. Wythe, the whole of his stomach and intestines had an uncommonly bloody appearance that if produced by arsenic, in his opinion, death would have ensued much sooner. Mr. Wythe frequently attacked with disordered bowels within three years last past.

Doctor McCaw Called on to attend Mr. Wythe the 26th of May between 4 and 5 o’clock. He had been up with a violent puking and purging, gave him an opiate, he got better, and was better until the discovery of Swinney’s forgery, when he became worse and continued to grow worse. He saw the boy on the day before his death, when he had a fever and complained of great pain. He saw him opened and thinks his death might have been occasioned by a great accumulation of bile.

Doctor Foushee Attended the opening of Mr. Wythe in the presence of many other physicians. The stomach much inflamed, and appeared as if a new inflammation was coming on. There was very little bile in the liver. The same appearance that his stomach and intestines exhibited might have been produced by arsenic

Page 9

or any other acrid matter.

A copy of the evidence in the case: Commonwealth v. Swinney – James [part of an R] James Robinson

See also

References

- ↑ Virginia Hustings Court Minute Book No. 3 (1802-1806), Richmond, Virginia. Microfilm at the Library of Virginia.

- ↑ George Lewis Chumbley, Colonial Justice in Virginia: The Development of a Judicial System, Typical Laws and Cases of the Period (Richmond: The Dietz Press, 1938), 77.

- ↑ John P. Alcock, "18th Century Virginia Law," Presentation at the Library of Virginia, November 17, 1999.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ W. Edwin Hemphill, "Examinations of George Wythe Swinney for Forgery and Murder: A Documentary Essay," in Julian P. Boyd and W. Edwin Hemphill, The Murder of George Wythe: Two Essays (Williamsburg, Va.: The Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1955), 40.

- ↑ Alcock, "18th Century Virginia Law."

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ "The minute book can be viewed as the clerk's own note-taking mechanism ... [T]he clerk made concise notes of the proceedings in the minute book during the court's session and later used these notes to create a more formal record of the court's activities ... in the order book." Rebecca G. Bates, "Official Court Records in Print," in Virginia Law Books: Essays and Bibliographies ed. by W. Hamilton Bryson (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2000): 130.