Difference between revisions of "Pendleton v. Hoomes"

(→Background) |

(→The Court's Decision) |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

==The Court's Decision== | ==The Court's Decision== | ||

| − | The High Court of Chancery found that Joseph's language about Benjamin's children referred to children | + | The High Court of Chancery decreed for the Pendletons. |

| + | |||

| + | Wythe found that Joseph's language about Benjamin's children referred to children alive when he died and the will was executed, not the children alive when he wrote the will. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To hold otherwise, Wythe said, would contravene Joseph's intent, since there is a possibility that English law<ref>Wythe's exact words: "if some decisions of the english courts be orthodox". Wythe 95.</ref> would have required all of Martha's share to go to John. In that scenario, the remainder of Joseph's estate would not have been split among Benjamin's children and John, "share and share alike"; rather, John would have received an extra seventh. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 17:05, 18 June 2014

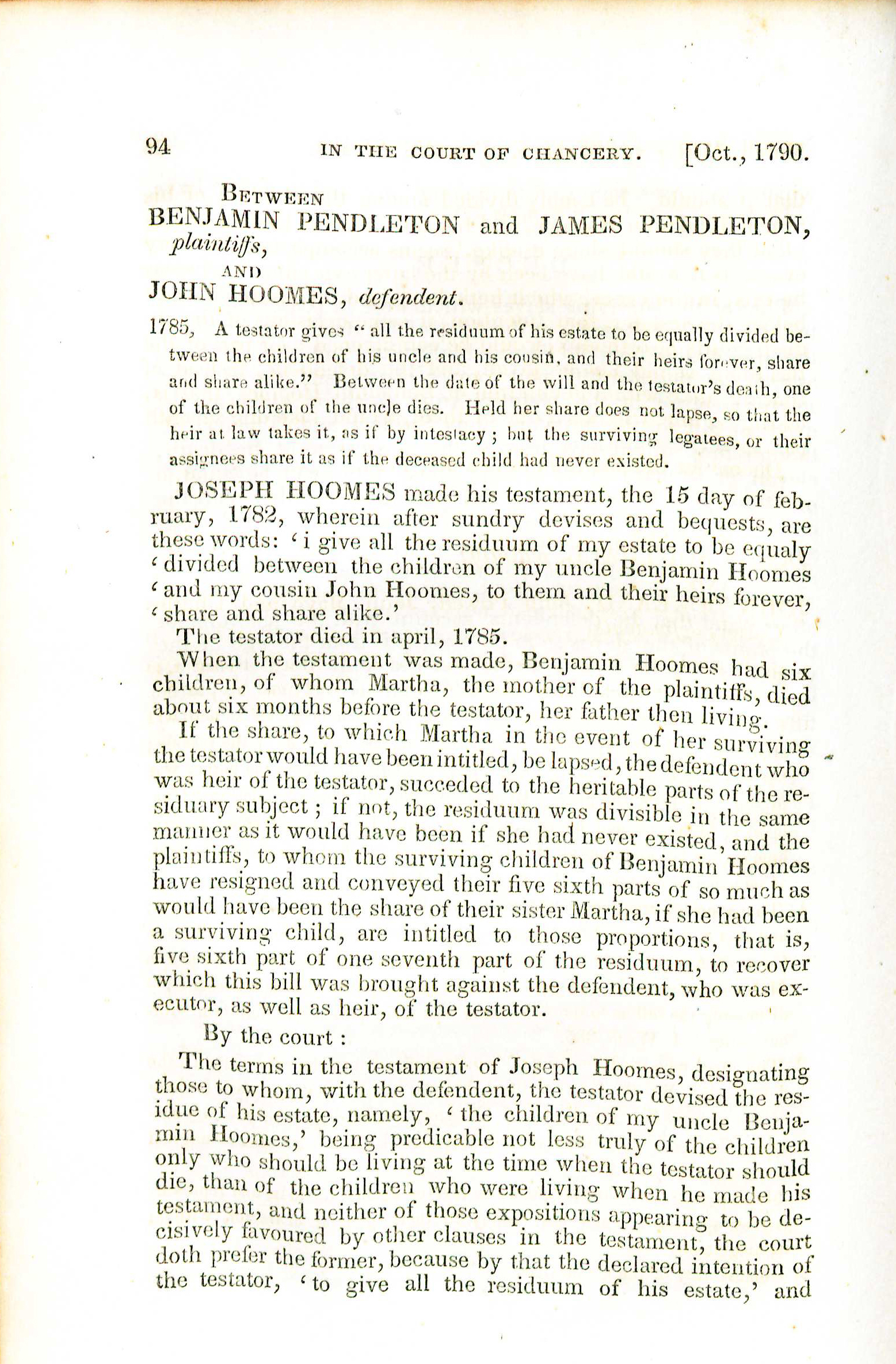

Pendleton v. Hoomes, Wythe 94 (1790), was a case discussing how an inheritance was to be split among surviving siblings.[1]

Background

In his will, Joseph Hoomes left the remaining part of his estate "to be equaly divided between the children of my uncle Benjamin Hoomes and my cousin John Hoomes. . .share and share alike." John Hoomes, the defendant, was Joseph's legal heir (i.e., the person who would inherit property not designated to go to someone else by a will).

When Joseph created the will, Benjamin Hoomes had six children. One of these children, Martha, died about six months before Joseph. Benjamin's other five children gave their inheritance rights to the plaintiffs, Benjamin and James Pendleton.

The Pendletons filed a bill with the High Court of Chancery to claim Martha's share of the inheritance, claiming that Martha's inheritance became invalid when she died.

The Court's Decision

The High Court of Chancery decreed for the Pendletons.

Wythe found that Joseph's language about Benjamin's children referred to children alive when he died and the will was executed, not the children alive when he wrote the will.

To hold otherwise, Wythe said, would contravene Joseph's intent, since there is a possibility that English law[2] would have required all of Martha's share to go to John. In that scenario, the remainder of Joseph's estate would not have been split among Benjamin's children and John, "share and share alike"; rather, John would have received an extra seventh.

References

- ↑ George Wythe, Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery, 94 (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 2d ed. 1852).

- ↑ Wythe's exact words: "if some decisions of the english courts be orthodox". Wythe 95.