Difference between revisions of "Hai tou Aischylou Trageodiai Seozomenai Hepta"

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

|set=2 volumes in 1 | |set=2 volumes in 1 | ||

|desc=p 4to (17 cm.) | |desc=p 4to (17 cm.) | ||

| − | }}[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aeschylus Aeschylus] was an Athenian poet born around 525 BCE. <ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192801463.001.0001/acref-9780192801463-e-52 "Aeschylus"] in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World'', ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).</ref> He was fortunate being born into a noble family, as well as watching the fall of tyranny and growth of democracy in Athens. Furthermore, Aeschylus is the earliest great Greek tragic poet whose work still remains.<ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-0069 "Ae'schylus”] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'', ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> His epitaph (c.456 BCE) reveals the importance (either to him or his family) of his status as “a loyal and courageous citizen of a free Athens” by discussing only his skilled fighting in the battle of Marathon. There is no mention of his writing, despite the fact that he wrote an estimated 70-90 plays from 499 BCE until his death. Aeschylus favored tetralogies, which were three tragedies composing a trilogy followed by a satire on the same or similar topic. Unfortunately, only seven of his plays survive to this day: ''Persians'', ''Seven against Thebes'', ''Suppliant'', the ''Oresteia'' trilogy (''Agamemnon'', ''Libation-bearers'', ''Euminides'') and ''Prometheus Bound''.<ref>"Aeschylus" in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World''.</ref> All seven are contained in | + | }}[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aeschylus Aeschylus] was an Athenian poet born around 525 BCE. <ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192801463.001.0001/acref-9780192801463-e-52 "Aeschylus"] in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World'', ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).</ref> He was fortunate being born into a noble family, as well as watching the fall of tyranny and growth of democracy in Athens. Furthermore, Aeschylus is the earliest great Greek tragic poet whose work still remains.<ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-0069 "Ae'schylus”] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'', ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> His epitaph (c.456 BCE) reveals the importance (either to him or his family) of his status as “a loyal and courageous citizen of a free Athens” by discussing only his skilled fighting in the battle of Marathon. There is no mention of his writing, despite the fact that he wrote an estimated 70-90 plays from 499 BCE until his death. Aeschylus favored tetralogies, which were three tragedies composing a trilogy followed by a satire on the same or similar topic. Unfortunately, only seven of his plays survive to this day: ''Persians'', ''Seven against Thebes'', ''Suppliant'', the ''Oresteia'' trilogy (''Agamemnon'', ''Libation-bearers'', ''Euminides'') and ''Prometheus Bound''.<ref>"Aeschylus" in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World''.</ref> All seven are contained in ''Hai tou Aischylou Trageodiai Seozomenai Hepta'' (''The Seven Extant Tragedies of Aeschylus'').<br/> |

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| − | Aeschylus was a | + | Aeschylus was a "pioneer" in his field of historical drama and playwriting.<ref>William C. Kirk, Jr., “Aeschylus and Herodotus,” ''The Classical Journal'' 51, no. 2 (Nov. 1955), 83.</ref> Rather than focusing on the characters themselves, he constructed the plot to arrive at a key situation and event. “Even important figures in a play…can be almost without distinctive character traits.”<ref>"Aeschylus" in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World''.</ref> Aeschylus stressed the power of situations and events as a contrast to the “moral lesson of the impermanence of human power and success.<ref>Kirk, Jr., “Aeschylus and Herodotus,” 84.</ref> To further create the powerful situational aspects that illuminate the morals Aeschylus touted, he created strong and distinctive choruses for each of his plays, using music and dance to establish the theme and mood of the play and to direct it to its inevitable conclusion.<ref>"Aeschylus" in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World''.</ref> |

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

Revision as of 08:42, 4 April 2014

by Aeschylus

| Hai tou Aischylou Trageodiai Seozomenai Hepta | |

|

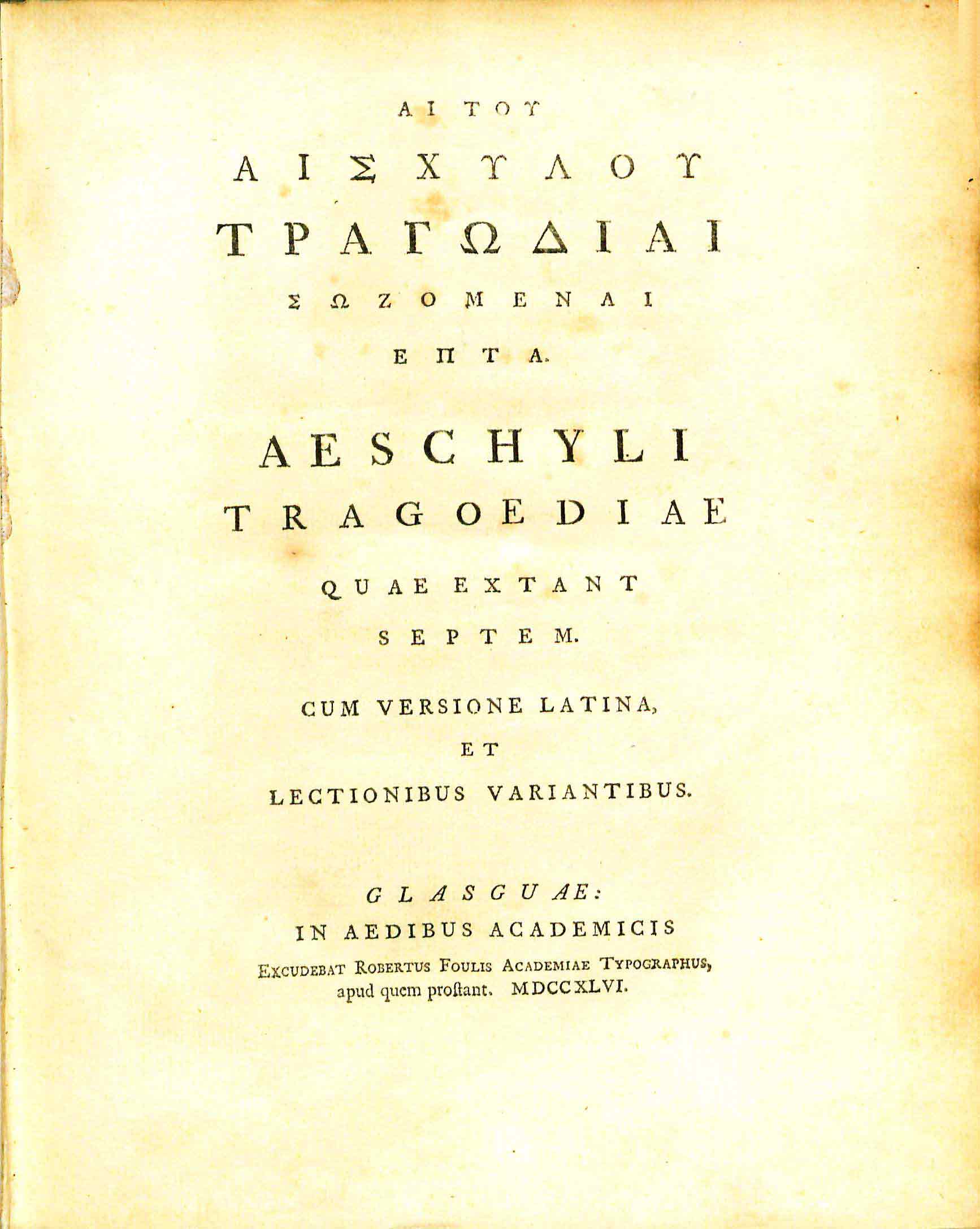

Title page from Hai tou Aischylou Trageodiai Seozomenai Hepta, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Aeschylus |

| Translator | Thomas Stanley |

| Published | Glasguæ: In aedibus academicis excudebat R. Foulis academiae typographys |

| Date | 1746 |

| Language | Greek and Latin parallel text |

| Volumes | 2 volumes in 1 volume set |

| Desc. | p 4to (17 cm.) |

Aeschylus was an Athenian poet born around 525 BCE. [1] He was fortunate being born into a noble family, as well as watching the fall of tyranny and growth of democracy in Athens. Furthermore, Aeschylus is the earliest great Greek tragic poet whose work still remains.[2] His epitaph (c.456 BCE) reveals the importance (either to him or his family) of his status as “a loyal and courageous citizen of a free Athens” by discussing only his skilled fighting in the battle of Marathon. There is no mention of his writing, despite the fact that he wrote an estimated 70-90 plays from 499 BCE until his death. Aeschylus favored tetralogies, which were three tragedies composing a trilogy followed by a satire on the same or similar topic. Unfortunately, only seven of his plays survive to this day: Persians, Seven against Thebes, Suppliant, the Oresteia trilogy (Agamemnon, Libation-bearers, Euminides) and Prometheus Bound.[3] All seven are contained in Hai tou Aischylou Trageodiai Seozomenai Hepta (The Seven Extant Tragedies of Aeschylus).

Aeschylus was a "pioneer" in his field of historical drama and playwriting.[4] Rather than focusing on the characters themselves, he constructed the plot to arrive at a key situation and event. “Even important figures in a play…can be almost without distinctive character traits.”[5] Aeschylus stressed the power of situations and events as a contrast to the “moral lesson of the impermanence of human power and success.[6] To further create the powerful situational aspects that illuminate the morals Aeschylus touted, he created strong and distinctive choruses for each of his plays, using music and dance to establish the theme and mood of the play and to direct it to its inevitable conclusion.[7]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as Aeschylus. Gr. Lat. 2.v. p. 4to. Foul. This was one of the books kept by Thomas Jefferson. Wythe also mentions reading Aeschylus with Jefferson's nephew, Peter Carr, in a letter to Jefferson dated December 13, 1786, "Peter Carr attends the professors of natural and moral philosophy and mathematics, is learning the French and Spanish languages, and with me reads Aeschylus and Horace, one day, and Herodotus and Cicero’s orations." Jefferson owned many copies of Aeschylus and later sold one which matches the description of the Wythe copy to the Library of Congress in 1815, but it no longer exists to verify Wythe's prior ownership.[8] Both the Brown Bibliography[9] and George Wythe's Library[10] on LibraryThing include the 1746 Foulis edition of Hai tou Aischylou Trageodiai Seozomenai Hepta—the only Greek and Latin Foulis version of the tragedies of Aeschylus produced before the 1786 date of Wythe's letter. The Wolf Law Library purchased a copy of the same edition.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in contemporary acid stained calf. Spine features five raised bands with gilt decorative compartments and a gilt label. Fore edge speckled. Purchased from Rosenlund Rare Books & Manuscripts.

View this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

References

- ↑ "Aeschylus" in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World, ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- ↑ "Ae'schylus” in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- ↑ "Aeschylus" in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World.

- ↑ William C. Kirk, Jr., “Aeschylus and Herodotus,” The Classical Journal 51, no. 2 (Nov. 1955), 83.

- ↑ "Aeschylus" in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World.

- ↑ Kirk, Jr., “Aeschylus and Herodotus,” 84.

- ↑ "Aeschylus" in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World.

- ↑ E. Millicent Sowerby, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, 2nd ed. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983), 4:529 (no.4524).

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

- ↑ LibraryThing, s. v. "Member: George Wythe", accessed February 26, 2014.