Difference between revisions of "Euripidis Tragœdiæ Medea et Phœnissæ"

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

|pages=[40],392 | |pages=[40],392 | ||

|desc=8vo (23 cm.) | |desc=8vo (23 cm.) | ||

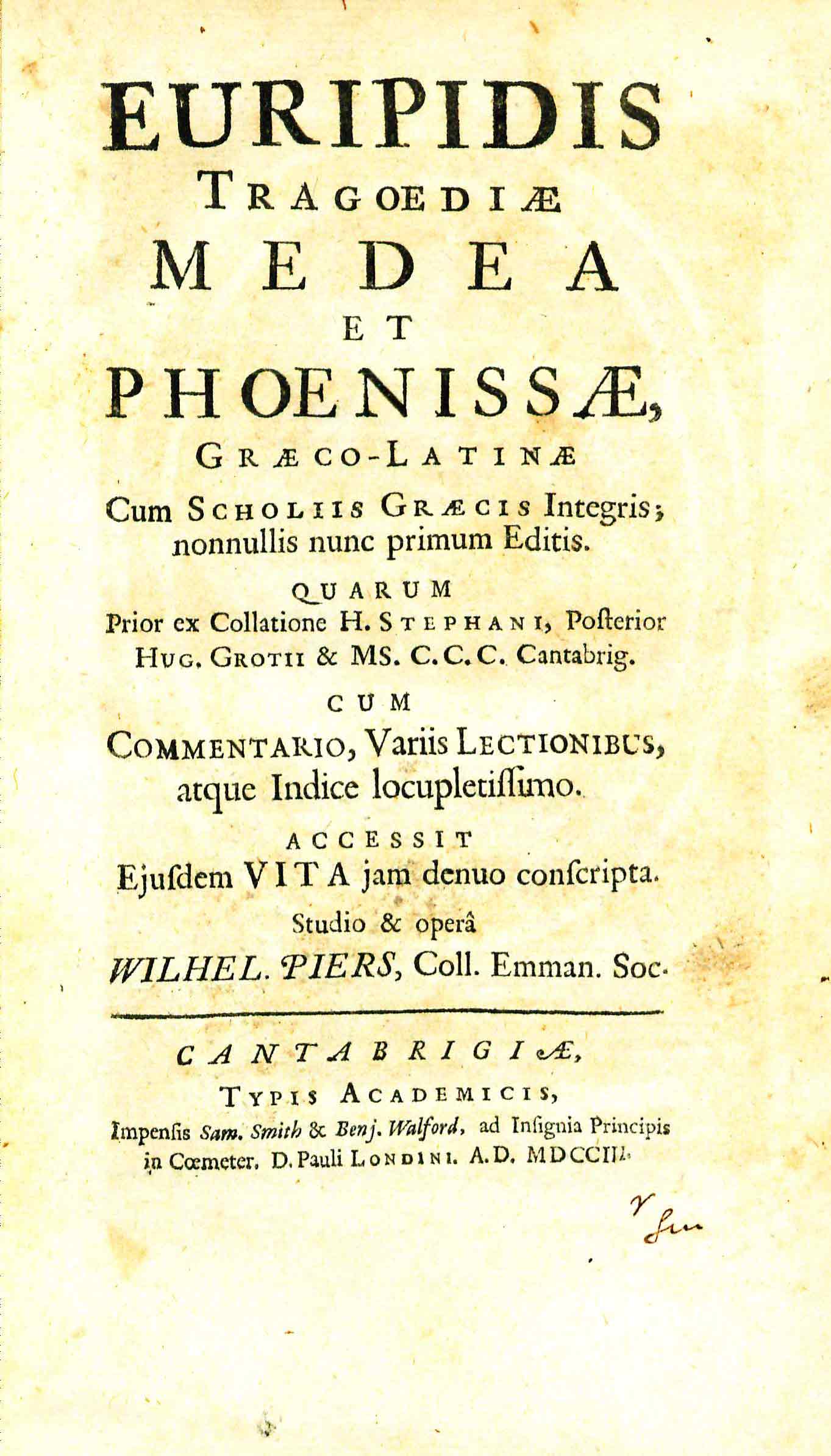

| − | }}[[File:EuripidisTrageodiaeMedeaEtPhoenissae1703Frontispiece.jpg|left|thumb|250px|<center>Frontispiece.</center>]][http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euripides Euripides] was an Athenian tragic poet/playwright who lived c. 485 | + | }}[[File:EuripidisTrageodiaeMedeaEtPhoenissae1703Frontispiece.jpg|left|thumb|250px|<center>Frontispiece.</center>]][http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euripides Euripides] was an Athenian tragic poet/playwright who lived from c. 485 to 406 BCE. He was the youngest of the three great Athenian tragedians, the other two being Aeschylus and Sophocles.<ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-1242 "Euri'pidēs"] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'', ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> Little is known about Euripides' life, though we do know that he was interested in the human mind. He associated with sophists such as Anaxagoras, Socrates and Protagoras, and disregarded the temptation of using his fame to become a prominent political player in Athens.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Euripides won just four victories at the famous Dionysia theater competition, ranking him much lower than Aeschylus and Sophocles, with 13 and 18 victories respectively.<ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192801463.001.0001/acref-9780192801463-e-853 "Euripidēs"] in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World'', ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).</ref> However, more than twice the number of Euripides’ plays have survived to modern times than those of Aeschylus or Sophocles.<ref>Ibid.</ref><br /> |

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| + | Euripides allegedly wrote 92 plays, 80 for which titles are known, and 19 of which are extant.<ref>"Euri'pidēs” in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature''.</ref> Extreme emotions and unorthodox events are prevalent in Euripides’ writing, often shown through the use of the Chorus. His characters battle societal pressures, torturous situations, and inner conflicts, highlighting "his awareness that personality is inherently a fragmented thing, different aspects being displayed at different times."<ref>Ibid.</ref> Toward the end of his life, Euripides' plays became less tragic, offering audiences an easier experience without having to face painful reality as closely, and the importance of the Chorus and the prevalence of songs decreased.<ref>"Euripidēs" in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World''.</ref><br/> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

This work contains two of Euripides’ plays: ''Medea'' and ''The Phoenician Women''. They are presented in both Greek and Latin, with additional Greek comments. ''Medea'' is the story of a “barbarian” woman (sometimes called a witch for her medicinal powers) scorned by her husband when he decides to advance his position by leaving her and their two children in order to marry Glauce, the princess of Corinth, where they settled after they met and went through a series of adventures (told in the store of Jason and the Golden Fleece or Jason and the Argonauts). The king of Corinth, Creon, fears Medea will seek revenge against his daughter and new son-in-law, and banishes Medea, but gives her one day. He lives to regret this because Medea quickly plans and uses that day to secure a place of safety in Athens after she kills Jason, his new wife and the king. Medea gives Glauce a poisoned dress and coronet killing her brutally. Creon embraces his daughter in grief, choosing to die with her. In her final act of murder, Medea kills her two children in order to leave Jason with absolutely nothing. She then escapes with the help of her grandfather, the Sun-God, who gives her a dragon-pulled chariot.<br/> | This work contains two of Euripides’ plays: ''Medea'' and ''The Phoenician Women''. They are presented in both Greek and Latin, with additional Greek comments. ''Medea'' is the story of a “barbarian” woman (sometimes called a witch for her medicinal powers) scorned by her husband when he decides to advance his position by leaving her and their two children in order to marry Glauce, the princess of Corinth, where they settled after they met and went through a series of adventures (told in the store of Jason and the Golden Fleece or Jason and the Argonauts). The king of Corinth, Creon, fears Medea will seek revenge against his daughter and new son-in-law, and banishes Medea, but gives her one day. He lives to regret this because Medea quickly plans and uses that day to secure a place of safety in Athens after she kills Jason, his new wife and the king. Medea gives Glauce a poisoned dress and coronet killing her brutally. Creon embraces his daughter in grief, choosing to die with her. In her final act of murder, Medea kills her two children in order to leave Jason with absolutely nothing. She then escapes with the help of her grandfather, the Sun-God, who gives her a dragon-pulled chariot.<br/> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

Revision as of 16:03, 14 March 2014

Euripidis Tragœdiæ Medea et Phœnissæ: Græco-Latinæ cum Scholiis Græcis Integris

by Euripides

| Euripidis Tragœdiæ Medea et Phœnissæ | |

|

Title page from Euripidis Tragœdiæ Medea et Phœnissæ, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Euripides |

| Editor | William Piers |

| Published | Cantabrigiae: Typis academicis, impensis Sam. Smith & Benj. Walford. D. Pauli Londini. |

| Date | 1703 |

| Language | Parallel Greek and Latin texts |

| Pages | [40],392 |

| Desc. | 8vo (23 cm.) |

Euripides allegedly wrote 92 plays, 80 for which titles are known, and 19 of which are extant.[5] Extreme emotions and unorthodox events are prevalent in Euripides’ writing, often shown through the use of the Chorus. His characters battle societal pressures, torturous situations, and inner conflicts, highlighting "his awareness that personality is inherently a fragmented thing, different aspects being displayed at different times."[6] Toward the end of his life, Euripides' plays became less tragic, offering audiences an easier experience without having to face painful reality as closely, and the importance of the Chorus and the prevalence of songs decreased.[7]

This work contains two of Euripides’ plays: Medea and The Phoenician Women. They are presented in both Greek and Latin, with additional Greek comments. Medea is the story of a “barbarian” woman (sometimes called a witch for her medicinal powers) scorned by her husband when he decides to advance his position by leaving her and their two children in order to marry Glauce, the princess of Corinth, where they settled after they met and went through a series of adventures (told in the store of Jason and the Golden Fleece or Jason and the Argonauts). The king of Corinth, Creon, fears Medea will seek revenge against his daughter and new son-in-law, and banishes Medea, but gives her one day. He lives to regret this because Medea quickly plans and uses that day to secure a place of safety in Athens after she kills Jason, his new wife and the king. Medea gives Glauce a poisoned dress and coronet killing her brutally. Creon embraces his daughter in grief, choosing to die with her. In her final act of murder, Medea kills her two children in order to leave Jason with absolutely nothing. She then escapes with the help of her grandfather, the Sun-God, who gives her a dragon-pulled chariot.

The Phoenician Women is a variant on the Oedipal Trilogy play “Seven Against Thebes” by Aeschylus. It tells the story of the war between Oedipus and Jocasta’s sons Eteocles and Polyneices. They locked their father away to hopefully keep people from talking about his detestable actions (killing his father and marrying his mother), but Oedipus cursed them both saying neither would rule without killing the other. The brothers worked out a system to share the throne by switching positions each year, but after Eteocles rules for his year, he decides not to abdicate and give the throne to his brother. Polyneices goes to Argos and marries the daughter of the king who sends him back to Thebes with an army so he can reconquer it. Euripides notably kept Jocasta alive in his version of the story rather than having her commit suicide. She arranges a cease-fire and serves as a mediator between her sons, but they cannot resolve their dispute. Creon, Jocasta’s brother, learns from the prophet Teiresias that he must sacrifice his son to end the war. Though Creon sends him away to safety, his son sacrifices himself to appease the war god Ares. None of this is known before Eteocles and Polyneices agree to single combat and mortally wound each other. Jocasta kills herself out of grief, then Antigone goes with her father Oedipus into exile in Athens after breaking off her engagement with Creon’s other son Haemon.

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as "Euripidis Medea et Phoenissae. Gr. Lat. Piers. cum scholii." This was one of the books kept by Thomas Jefferson. He later sold a copy of the same title to the Library of Congress in 1815, but it no longer exists to verify Wythe's prior ownership.[8] Both the Brown Bibliography[9] and George Wythe's Library[10] on LibraryThing include the Cambridge 1703 edition based on E. Millicent Sowerby's inclusion of that edition in Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson. The Wolf Law Library purchased a copy of the same edition.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in contemporary panelled calf. Includes the bookplate of Arbury Library on the front pastedown. Purchased from Sevin Seydi Rare Books.

References

- ↑ "Euri'pidēs" in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ "Euripidēs" in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World, ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ "Euri'pidēs” in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ "Euripidēs" in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World.

- ↑ E. Millicent Sowerby, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson 2nd ed. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983), 4:530-531 (no.4526).

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

- ↑ LibraryThing, s. v. "Member: George Wythe", accessed February 27, 2014.