Difference between revisions of "Works of Francis Rabelais"

(JH edits) |

|||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

|desc=12mo (17 cm.) | |desc=12mo (17 cm.) | ||

}}[[File:RabelaisWorks1737v1Frontispiece.jpg|left|thumb|250px|<center>Frontispiece, volume one.</center>]] | }}[[File:RabelaisWorks1737v1Frontispiece.jpg|left|thumb|250px|<center>Frontispiece, volume one.</center>]] | ||

| − | [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fran%C3%A7ois_Rabelais François Rabelais] (c. 1495-1553) was a physician, priest, and notable writer | + | [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fran%C3%A7ois_Rabelais François Rabelais] (c. 1495-1553) was a physician, priest, and notable writer<ref>“Francois Rabelais, M.D.,” ''The British Medical Journal'', 1, No. 4814 (1953), 831.</ref> who was well studied in the classics.<ref> [http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/487941/Francois-Rabelais “François Rabelais,”] ''Encyclopædia Britannica Online'' (Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013- ), accessed October 28, 2013.</ref> Around 1521, Rabelais became a priest, but broke his vows in 1530 to study medicine.<ref> Ibid.</ref> He was one of the first, if not the first, physicians to dissect the human body.<ref> “Francois Rabelais, M.D.,” ''The British Medical Journal''.</ref> In 1532 he became head physician at a hospital in Lyons, and he began to write.<ref> Ibid.</ref><br/> |

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| − | + | Rabelais’ works are famous for their bawdy, satirical nature.<ref>“François Rabelais,” ''Encyclopædia Britannica Online''.</ref> His style is so distinct, the Oxford English Dictionary includes the adjective “Rabelaisian” to describe writings with “earthy humour, [a] parody of medieval learning and literature, and [an] affirmation of humanist values.”<ref>[http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/157008#eid27221738 “Rabelaisian, adj.,”] ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (OED Third Edition, June 2008), accessed October 28, 2013.</ref><br/> | |

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| − | + | Rabelais' most famous works are the Gargantua-Pantagruel series, four books published from 1532 to 1535.<ref> “François Rabelais,” ''Encyclopædia Britannica Online''.</ref> Framed as chivalric romances, they use the theatrical language of vaudeville to satirize heroic works, traditional pedagogy, and humanist ideals.<ref> Ibid.</ref> He grotesquely caricatured people in a playful way, in a style extensively imitated by seventeenth and eighteenth century French writers.<ref>Dorothy S. Packer, “François Rabelais, Vaudevilliste,” ''The Musical Quarterly'', 57, No. 1 (1971), 127.</ref> | |

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

Revision as of 21:34, 16 March 2014

by François Rabelais

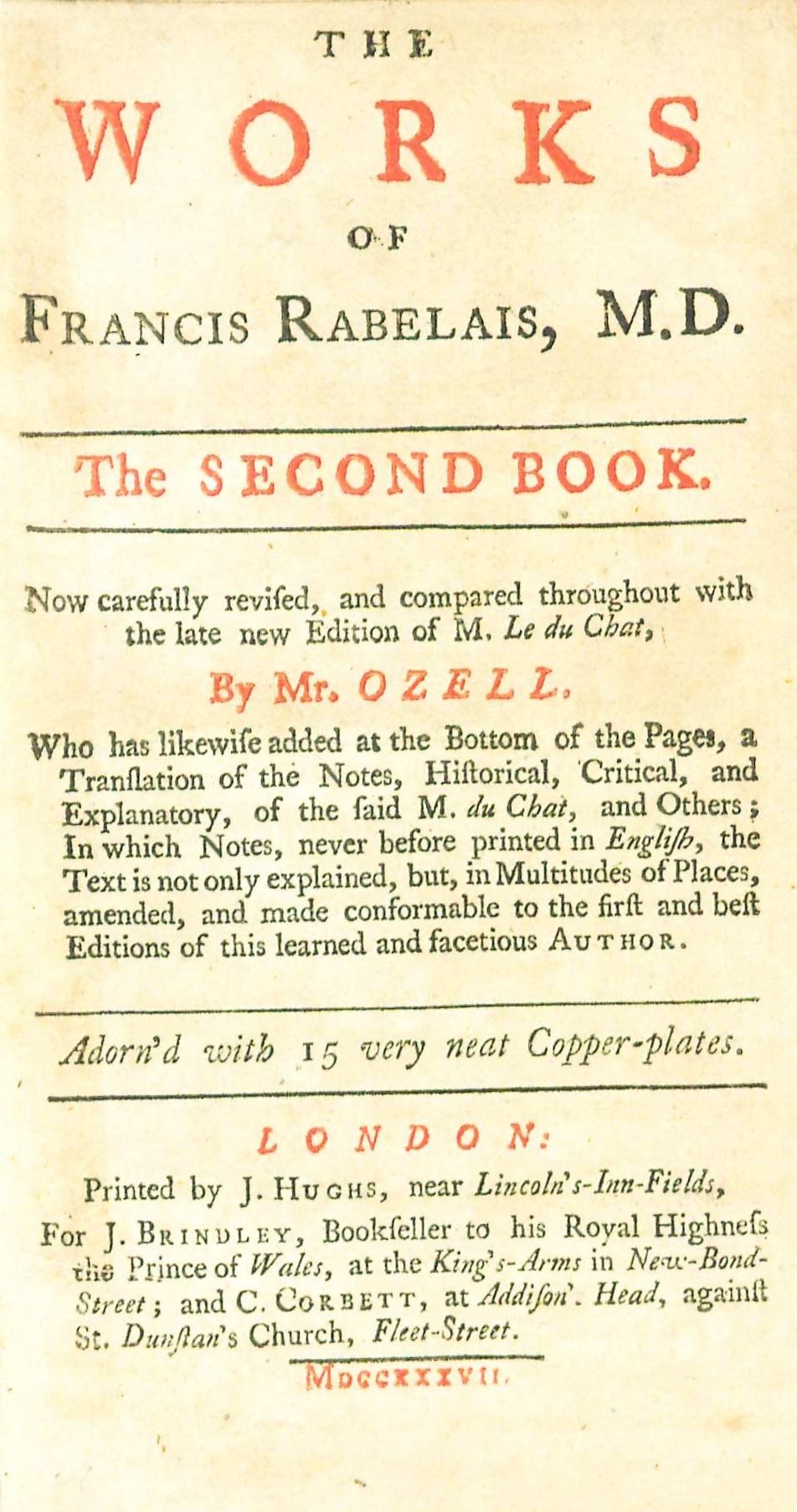

| The Works of Francis Rabelais | |

|

Title page from The Works of Francis Rabelais, volume three, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | François Rabelais |

| Editor | Peter Anthony Motteux |

| Translator | Sir Thomas Urquhart |

| Published | London: Printed by J. Hughs for J. Brindley and C. Corbett |

| Date | 1737 |

| Language | English |

| Volumes | 5 volume set |

| Desc. | 12mo (17 cm.) |

François Rabelais (c. 1495-1553) was a physician, priest, and notable writer[1] who was well studied in the classics.[2] Around 1521, Rabelais became a priest, but broke his vows in 1530 to study medicine.[3] He was one of the first, if not the first, physicians to dissect the human body.[4] In 1532 he became head physician at a hospital in Lyons, and he began to write.[5]

Rabelais’ works are famous for their bawdy, satirical nature.[6] His style is so distinct, the Oxford English Dictionary includes the adjective “Rabelaisian” to describe writings with “earthy humour, [a] parody of medieval learning and literature, and [an] affirmation of humanist values.”[7]

Rabelais' most famous works are the Gargantua-Pantagruel series, four books published from 1532 to 1535.[8] Framed as chivalric romances, they use the theatrical language of vaudeville to satirize heroic works, traditional pedagogy, and humanist ideals.[9] He grotesquely caricatured people in a playful way, in a style extensively imitated by seventeenth and eighteenth century French writers.[10]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as Rabelais. 5.v. 12mo. 2d. wanting and given by Thomas Jefferson to his son-in-law, Thomas Mann Randolph. Later appears on Randolph's 1832 estate inventory as "'Rabellais Works' (4 vols., $2.12 1/2 value)." We do not have enough information to conclusively identify which edition Wythe owned. George Wythe's Library[11] on LibraryThing indicates this, adding "English translations in five volumes were published at London in 1737, 1738, and 1750." The Brown Bibliography[12] lists the 1750 edition based on the copy Jefferson sold to the Library of Congress.[13] The Wolf Law Library purchased the 1750 edition.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in contemporary full calf bindings, blind tooled and gold ruled. Purchased from Book Den East.

View this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

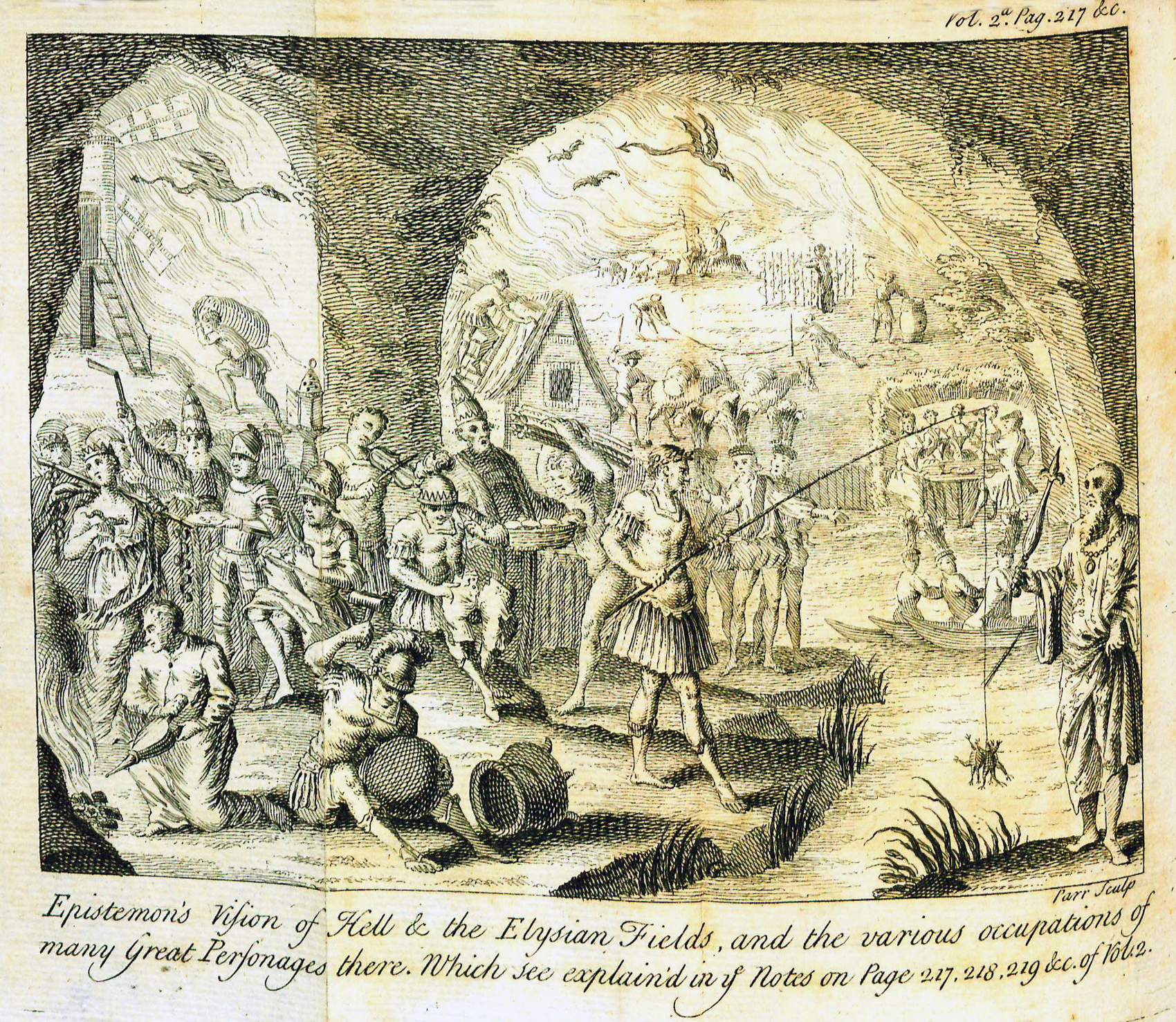

- RabelaisWorks1737v5Illustration.jpg

Illustration, volume five.

References

- ↑ “Francois Rabelais, M.D.,” The British Medical Journal, 1, No. 4814 (1953), 831.

- ↑ “François Rabelais,” Encyclopædia Britannica Online (Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013- ), accessed October 28, 2013.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ “Francois Rabelais, M.D.,” The British Medical Journal.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ “François Rabelais,” Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ “Rabelaisian, adj.,” Oxford English Dictionary (OED Third Edition, June 2008), accessed October 28, 2013.

- ↑ “François Rabelais,” Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Dorothy S. Packer, “François Rabelais, Vaudevilliste,” The Musical Quarterly, 57, No. 1 (1971), 127.

- ↑ LibraryThing, s. v. "Member: George Wythe", accessed on November 13, 2013.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

- ↑ E. Millicent Sowerby, ""Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson 2nd ed. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983), 4:444 [no. 4333].