Difference between revisions of "Xenophontos Hellenika"

(→by Xenophon) |

(→by Xenophon) |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

Xenophon (c.428-c.354BCE) was an Athenian historian and disciple of Socrates who had a somewhat turbulent relationship with his home city. He was born into a wealthy family and supported the short-lived oligarchic government of Athens in 411BCE which likely made it difficult for him when the democratic government was reinstated. <ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-3115 " Xe'nophon”] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'', ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> In 401, Xenophon joined a mercenary army and went on an expedition with the newly deceased Persian king’s son and commander Cyrus the Younger in an attempt to take the throne from his older brother. <ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-0913"Cȳrus”] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'', ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> After the failure of that attempted coup and Cyrus’s death, Xenophon returned to Greece with the rest of Cyrus’s army for whose “lawless behavior” Xenophon was made responsible <ref>G.L. Cawkwell, “Agesilaus and Sparta,” ''The Classical Quarterly'', New Series 26, no. 1 (1976): 64.</ref> until he impressed and joined the service of the Spartan king Agesilaus in 396BCE and fought on the Spartan side against Athens and Boeotia in 394. Either for this treachery or an earlier incident, Xenophon was exiled from Athens and his property was confiscated. The Spartans gave him an estate near Olympia and the position of entertaining visiting Spartans. For the next twenty years, he did just that while also writing his many books. He was forced from Olympia and moved to Corinth in 371BCE, then back to Athens in 366BCE after all Athenians were banished from Corinth (his exile from Athens was likely revoked around 368BCE). <ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-3115 " Xe'nophon”]</ref><br/> | Xenophon (c.428-c.354BCE) was an Athenian historian and disciple of Socrates who had a somewhat turbulent relationship with his home city. He was born into a wealthy family and supported the short-lived oligarchic government of Athens in 411BCE which likely made it difficult for him when the democratic government was reinstated. <ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-3115 " Xe'nophon”] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'', ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> In 401, Xenophon joined a mercenary army and went on an expedition with the newly deceased Persian king’s son and commander Cyrus the Younger in an attempt to take the throne from his older brother. <ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-0913"Cȳrus”] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'', ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> After the failure of that attempted coup and Cyrus’s death, Xenophon returned to Greece with the rest of Cyrus’s army for whose “lawless behavior” Xenophon was made responsible <ref>G.L. Cawkwell, “Agesilaus and Sparta,” ''The Classical Quarterly'', New Series 26, no. 1 (1976): 64.</ref> until he impressed and joined the service of the Spartan king Agesilaus in 396BCE and fought on the Spartan side against Athens and Boeotia in 394. Either for this treachery or an earlier incident, Xenophon was exiled from Athens and his property was confiscated. The Spartans gave him an estate near Olympia and the position of entertaining visiting Spartans. For the next twenty years, he did just that while also writing his many books. He was forced from Olympia and moved to Corinth in 371BCE, then back to Athens in 366BCE after all Athenians were banished from Corinth (his exile from Athens was likely revoked around 368BCE). <ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-3115 " Xe'nophon”]</ref><br/> | ||

| − | <br/>All known parts of the vast number of works which Xenophon produced have survived to the modern day. Most are in the three categories of “long (quasi-) historical narratives, Socratic texts, and technical treatises.” <ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192801463.001.0001/acref-9780192801463-e-2373 " Xenophon "] in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World'', ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).</ref> This particular edition of Xenophon’s works contains his ''Hellenica'' and ''Agesilaus''. The former is a chronological account of key military events from 411BCE to 362BCE contained in seven books. In these events, Xenophon combines historical narratives with starkly honest expositions of the shortcomings of different states, including Sparta. The latter work including in this volume is a posthumous biography of the Spartan king Agesilaus with whom Xenophon had a long and close relationship. Though the chronology is uneven and adds not additional information about the king which is not already included in ''Hellenica'', the work was crucial to the development of biography. Additionally, the list of principal virtues of “a perfectly good man” reveals Greek expectations and standards of the time. <ref>Ibid.</ref><br/> | + | <br/>All known parts of the vast number of works which Xenophon produced have survived to the modern day. Most are in the three categories of “long (quasi-) historical narratives, Socratic texts, and technical treatises.” <ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192801463.001.0001/acref-9780192801463-e-2373 " Xenophon "] in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World'', ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).</ref> This particular edition of Xenophon’s works contains his ''Hellenica'' and ''Agesilaus''. The former is a chronological account of key military events from 411BCE to 362BCE contained in seven books. In these events, Xenophon combines historical narratives with starkly honest expositions of the shortcomings of different states, including Sparta. The latter work including in this volume is a posthumous biography of the Spartan king Agesilaus with whom Xenophon had a long and close relationship. Though the chronology is uneven and adds not additional information about the king which is not already included in ''Hellenica'', the work was crucial to the development of biography. Additionally, the list of principal virtues of “a perfectly good man” reveals Greek expectations and standards of the time.<ref>Ibid.</ref><br/> |

| − | <br/>This work was published in 1762 by two well-known and regarded Scottish publishers. Robert and Andrew Foulis (''ne'' Faulls) were brothers who opened their own publishing company and printing press in 18th century Glasgow.<ref>David Murray, Robert & Andrew Foulis and the Glasgow Press with some account of The Glasgow Academy of the Fine Arts (Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons, Publishers to the University), 8.</ref> Robert was a barber before enrolling in University of Glasgow courses, while Andrew “received a more regular education…[as] a student of Humanity” who taught Greek, Latin and French for a time after he graduated.<ref>Ibid 3.</ref> The brothers began as booksellers and then transitioned to publishing and printing books, with Robert intiating each endeavor before later being joined by Andrew.<ref>Ibid 6-10.</ref> In 1740-42, Robert had other printers print what he chose to publish, but began printing his own books in 1742 which continued until his and his brother’s deaths in 1775 and 1776, respectively, when Andrew’s son Andrew took over The Foulis Press.<ref>Philip Gaskell, ''A Bibliography of the Foulis Press'', 2nd ed. (Winchester, Hampshire, England: St Paul's Bibliographies, 1986), 15-17.</ref> The Foulis Press primarily produced text books and other “works of learning…and of general literature,” as it was the printer to the University of Glasgow. | + | <br/>This work was published in 1762 by two well-known and regarded Scottish publishers. Robert and Andrew Foulis (''ne'' Faulls) were brothers who opened their own publishing company and printing press in 18th century Glasgow.<ref>David Murray, Robert & Andrew Foulis and the Glasgow Press with some account of The Glasgow Academy of the Fine Arts (Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons, Publishers to the University), 8.</ref> Robert was a barber before enrolling in University of Glasgow courses, while Andrew “received a more regular education…[as] a student of Humanity” who taught Greek, Latin and French for a time after he graduated.<ref>Ibid 3.</ref> The brothers began as booksellers and then transitioned to publishing and printing books, with Robert intiating each endeavor before later being joined by Andrew.<ref>Ibid 6-10.</ref> In 1740-42, Robert had other printers print what he chose to publish, but began printing his own books in 1742 which continued until his and his brother’s deaths in 1775 and 1776, respectively, when Andrew’s son Andrew took over The Foulis Press.<ref>Philip Gaskell, ''A Bibliography of the Foulis Press'', 2nd ed. (Winchester, Hampshire, England: St Paul's Bibliographies, 1986), 15-17.</ref> The Foulis Press primarily produced text books and other “works of learning…and of general literature,” as it was the printer to the University of Glasgow.<ref>Ibid 17-18</ref> The press is unique for the plethora of variant issues and editions of published books on special paper, in special font, or even on copper plates.<ref>Ibid 18-19.</ref> |

{{BookPageInfoBox | {{BookPageInfoBox | ||

Revision as of 16:55, 27 January 2014

Ta tou Xenophontos Hellenika : kai ho Agesilaos = : Xenophontis Graecorum res gestae : et Agesilaus

by Xenophon

Xenophon (c.428-c.354BCE) was an Athenian historian and disciple of Socrates who had a somewhat turbulent relationship with his home city. He was born into a wealthy family and supported the short-lived oligarchic government of Athens in 411BCE which likely made it difficult for him when the democratic government was reinstated. [1] In 401, Xenophon joined a mercenary army and went on an expedition with the newly deceased Persian king’s son and commander Cyrus the Younger in an attempt to take the throne from his older brother. [2] After the failure of that attempted coup and Cyrus’s death, Xenophon returned to Greece with the rest of Cyrus’s army for whose “lawless behavior” Xenophon was made responsible [3] until he impressed and joined the service of the Spartan king Agesilaus in 396BCE and fought on the Spartan side against Athens and Boeotia in 394. Either for this treachery or an earlier incident, Xenophon was exiled from Athens and his property was confiscated. The Spartans gave him an estate near Olympia and the position of entertaining visiting Spartans. For the next twenty years, he did just that while also writing his many books. He was forced from Olympia and moved to Corinth in 371BCE, then back to Athens in 366BCE after all Athenians were banished from Corinth (his exile from Athens was likely revoked around 368BCE). [4]

All known parts of the vast number of works which Xenophon produced have survived to the modern day. Most are in the three categories of “long (quasi-) historical narratives, Socratic texts, and technical treatises.” [5] This particular edition of Xenophon’s works contains his Hellenica and Agesilaus. The former is a chronological account of key military events from 411BCE to 362BCE contained in seven books. In these events, Xenophon combines historical narratives with starkly honest expositions of the shortcomings of different states, including Sparta. The latter work including in this volume is a posthumous biography of the Spartan king Agesilaus with whom Xenophon had a long and close relationship. Though the chronology is uneven and adds not additional information about the king which is not already included in Hellenica, the work was crucial to the development of biography. Additionally, the list of principal virtues of “a perfectly good man” reveals Greek expectations and standards of the time.[6]

This work was published in 1762 by two well-known and regarded Scottish publishers. Robert and Andrew Foulis (ne Faulls) were brothers who opened their own publishing company and printing press in 18th century Glasgow.[7] Robert was a barber before enrolling in University of Glasgow courses, while Andrew “received a more regular education…[as] a student of Humanity” who taught Greek, Latin and French for a time after he graduated.[8] The brothers began as booksellers and then transitioned to publishing and printing books, with Robert intiating each endeavor before later being joined by Andrew.[9] In 1740-42, Robert had other printers print what he chose to publish, but began printing his own books in 1742 which continued until his and his brother’s deaths in 1775 and 1776, respectively, when Andrew’s son Andrew took over The Foulis Press.[10] The Foulis Press primarily produced text books and other “works of learning…and of general literature,” as it was the printer to the University of Glasgow.[11] The press is unique for the plethora of variant issues and editions of published books on special paper, in special font, or even on copper plates.[12]

| Ta tou Xenophontos Hellenika | |

|

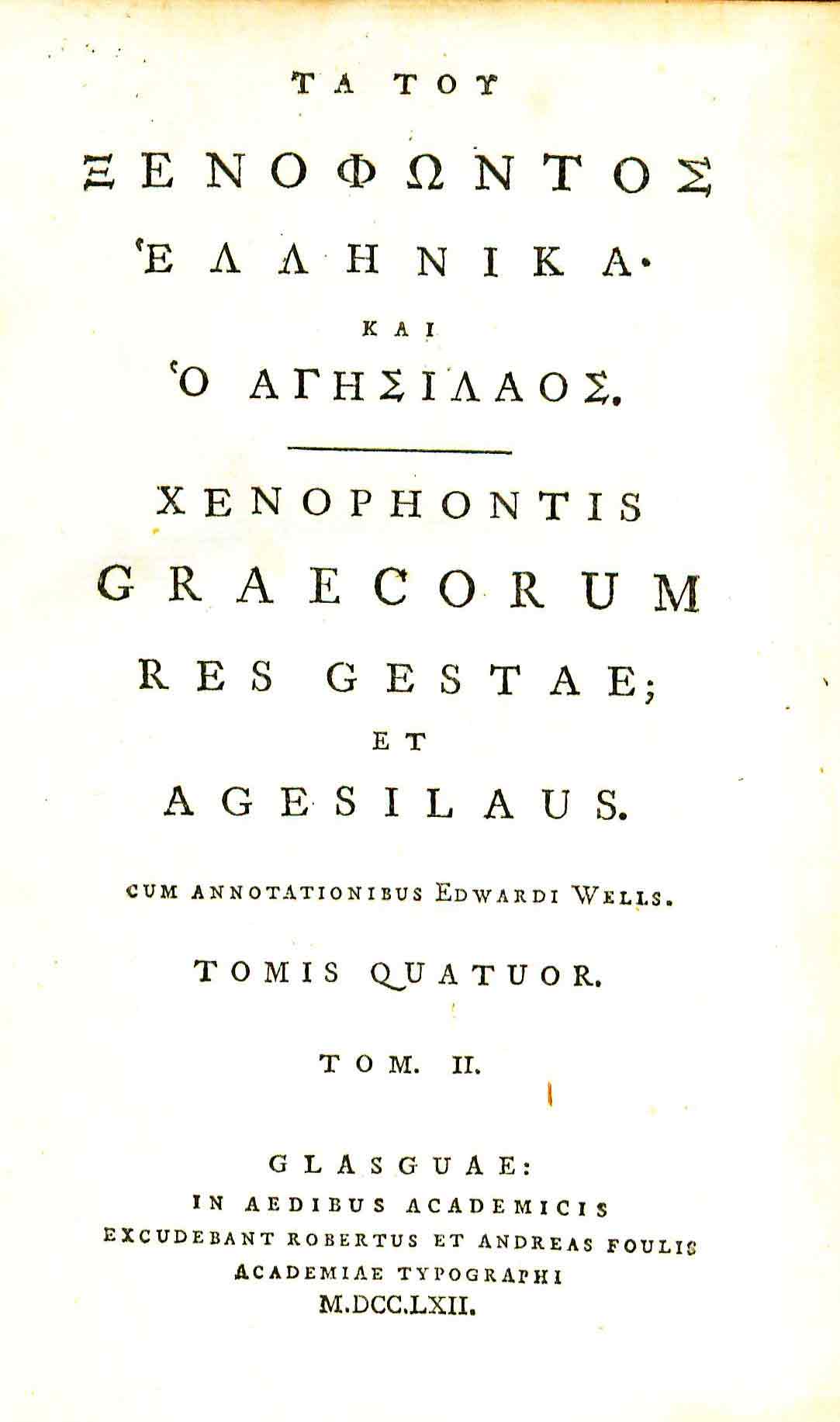

Title page from Ta tou Xenophontos Hellenika, volume two, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Xenophon |

| Editor | Edward Wells? |

| Published | Glasguae: R. et A. Foulis |

| Date | 1762 |

| Language | Greek and Latin |

| Volumes | 4 volume set |

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as Xenophontis historia. 4.v. 8vo. Foulis and given by Thomas Jefferson to John Wayles Eppes. According to Gaskell's bibliography, the Foulis Press published Xenophon's Hellenica and Agesilaus once, in 1762.[13] Both Brown's Bibliography[14] and George Wythe's Library[15] on LibraryThing include this title as the one intended by Jefferson's notation.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in full brown calf with red calf labels to spine. Text in Greek on one side and Latin on the other. Purchased from Schooner Books Ltd.

View this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

External Links

References

- ↑ " Xe'nophon” in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- ↑ "Cȳrus” in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- ↑ G.L. Cawkwell, “Agesilaus and Sparta,” The Classical Quarterly, New Series 26, no. 1 (1976): 64.

- ↑ " Xe'nophon”

- ↑ " Xenophon " in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World, ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ David Murray, Robert & Andrew Foulis and the Glasgow Press with some account of The Glasgow Academy of the Fine Arts (Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons, Publishers to the University), 8.

- ↑ Ibid 3.

- ↑ Ibid 6-10.

- ↑ Philip Gaskell, A Bibliography of the Foulis Press, 2nd ed. (Winchester, Hampshire, England: St Paul's Bibliographies, 1986), 15-17.

- ↑ Ibid 17-18

- ↑ Ibid 18-19.

- ↑ Philip Gaskell, A Bibliography of The Foulis Press, 2nd ed. (Winchester, Hampshire, England : St Paul's Bibliographies, 1986), 248.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

- ↑ LibraryThing, s. v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on June 28, 2013, http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe