Difference between revisions of "Anacreontis Odaria ad Textus Barnesiani Fidem Emendata"

(→by) |

|||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

===by === | ===by === | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

| − | Anacreon was a Greek lyric poet born around 570BCE in Teos, an Ionian city on the coast of Asia Minor. <ref>http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-0188 " Ana'creon”] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'', ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> He likely moved to Thrace in 545BCE with others from his city when it was attacked by Persians. Following that, he moved to Samos and then to Athens and possibly again to Thessaly, seeking a safe place to write his poems as his patrons kept being murdered (Polycrates, tyrant of Samos, and Hipparchus, brother of Athenian tyrant Hippias). <ref>Ibid.</ref> It is unknown where he died <ref>Ibid</ref>, though he made it to the unusually advanced age of 85 when he died in 485 BCE. <ref>Marty Roth, “’Anacreon’ and Drink Poetry; or, the Art of Feeling Very Very Good,” ''Texas Studies in Literature and Language'' 42, no. 3 (Fall 2000): 314.</ref><br/> | + | Anacreon was a Greek lyric poet born around 570BCE in Teos, an Ionian city on the coast of Asia Minor. <ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-0188 " Ana'creon”] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'', ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> He likely moved to Thrace in 545BCE with others from his city when it was attacked by Persians. Following that, he moved to Samos and then to Athens and possibly again to Thessaly, seeking a safe place to write his poems as his patrons kept being murdered (Polycrates, tyrant of Samos, and Hipparchus, brother of Athenian tyrant Hippias). <ref>Ibid.</ref> It is unknown where he died <ref>Ibid</ref>, though he made it to the unusually advanced age of 85 when he died in 485 BCE. <ref>Marty Roth, “’Anacreon’ and Drink Poetry; or, the Art of Feeling Very Very Good,” ''Texas Studies in Literature and Language'' 42, no. 3 (Fall 2000): 314.</ref><br/> |

<br/>Little of Anacreon’s actual works survives, but what does is focused almost solely on wine, love (homosexual and heterosexual) and the overall pleasures of the legendary Roman symposium <ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192801463.001.0001/acref-9780192801463-e-120 "Anacreon"] in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World'', ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).</ref> Anacreon utilized language to present clear images of love and to highlight the significant aspects of his writing through various techniques including self-deprecation and irony. <ref>Ibid.</ref> The collection of miscellaneous Greek poems from the Hellenistic Age and beyond known as the ''Anacreontea'' <ref>Ibid</ref> was “mistakenly labeled” with Anacreon’s name, a fact known and denied through antiquity and the Renaissance, but once the unequivocal truth of the false origin of these poems was known, their previous fame and praise was cast aside in exchange for derision <ref>Roth, “’Anacreon’ and Drink Poetry; or, the Art of Feeling Very Very Good,” 316-17.</ref> Unfortunately, despite the later appreciation for the ''true'' Anacreon’s poems, his works were not appreciated contemporaneously or throughout Europe during the Renaissance as the false ''Anacreontea'' <ref>Ibid at 317.</ref><br/> | <br/>Little of Anacreon’s actual works survives, but what does is focused almost solely on wine, love (homosexual and heterosexual) and the overall pleasures of the legendary Roman symposium <ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192801463.001.0001/acref-9780192801463-e-120 "Anacreon"] in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World'', ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).</ref> Anacreon utilized language to present clear images of love and to highlight the significant aspects of his writing through various techniques including self-deprecation and irony. <ref>Ibid.</ref> The collection of miscellaneous Greek poems from the Hellenistic Age and beyond known as the ''Anacreontea'' <ref>Ibid</ref> was “mistakenly labeled” with Anacreon’s name, a fact known and denied through antiquity and the Renaissance, but once the unequivocal truth of the false origin of these poems was known, their previous fame and praise was cast aside in exchange for derision <ref>Roth, “’Anacreon’ and Drink Poetry; or, the Art of Feeling Very Very Good,” 316-17.</ref> Unfortunately, despite the later appreciation for the ''true'' Anacreon’s poems, his works were not appreciated contemporaneously or throughout Europe during the Renaissance as the false ''Anacreontea'' <ref>Ibid at 317.</ref><br/> | ||

<br/>This particular work is a collection of the extant Odes by Anacreon published in Ancient Greek with no notes or commentary. | <br/>This particular work is a collection of the extant Odes by Anacreon published in Ancient Greek with no notes or commentary. | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

|set=1 | |set=1 | ||

}} | }} | ||

| + | |||

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

Revision as of 16:09, 23 January 2014

by

Anacreon was a Greek lyric poet born around 570BCE in Teos, an Ionian city on the coast of Asia Minor. [1] He likely moved to Thrace in 545BCE with others from his city when it was attacked by Persians. Following that, he moved to Samos and then to Athens and possibly again to Thessaly, seeking a safe place to write his poems as his patrons kept being murdered (Polycrates, tyrant of Samos, and Hipparchus, brother of Athenian tyrant Hippias). [2] It is unknown where he died [3], though he made it to the unusually advanced age of 85 when he died in 485 BCE. [4]

Little of Anacreon’s actual works survives, but what does is focused almost solely on wine, love (homosexual and heterosexual) and the overall pleasures of the legendary Roman symposium [5] Anacreon utilized language to present clear images of love and to highlight the significant aspects of his writing through various techniques including self-deprecation and irony. [6] The collection of miscellaneous Greek poems from the Hellenistic Age and beyond known as the Anacreontea [7] was “mistakenly labeled” with Anacreon’s name, a fact known and denied through antiquity and the Renaissance, but once the unequivocal truth of the false origin of these poems was known, their previous fame and praise was cast aside in exchange for derision [8] Unfortunately, despite the later appreciation for the true Anacreon’s poems, his works were not appreciated contemporaneously or throughout Europe during the Renaissance as the false Anacreontea [9]

This particular work is a collection of the extant Odes by Anacreon published in Ancient Greek with no notes or commentary.

| Anacreontis Odaria ad textus Barnesiani fidem emendata | |

|

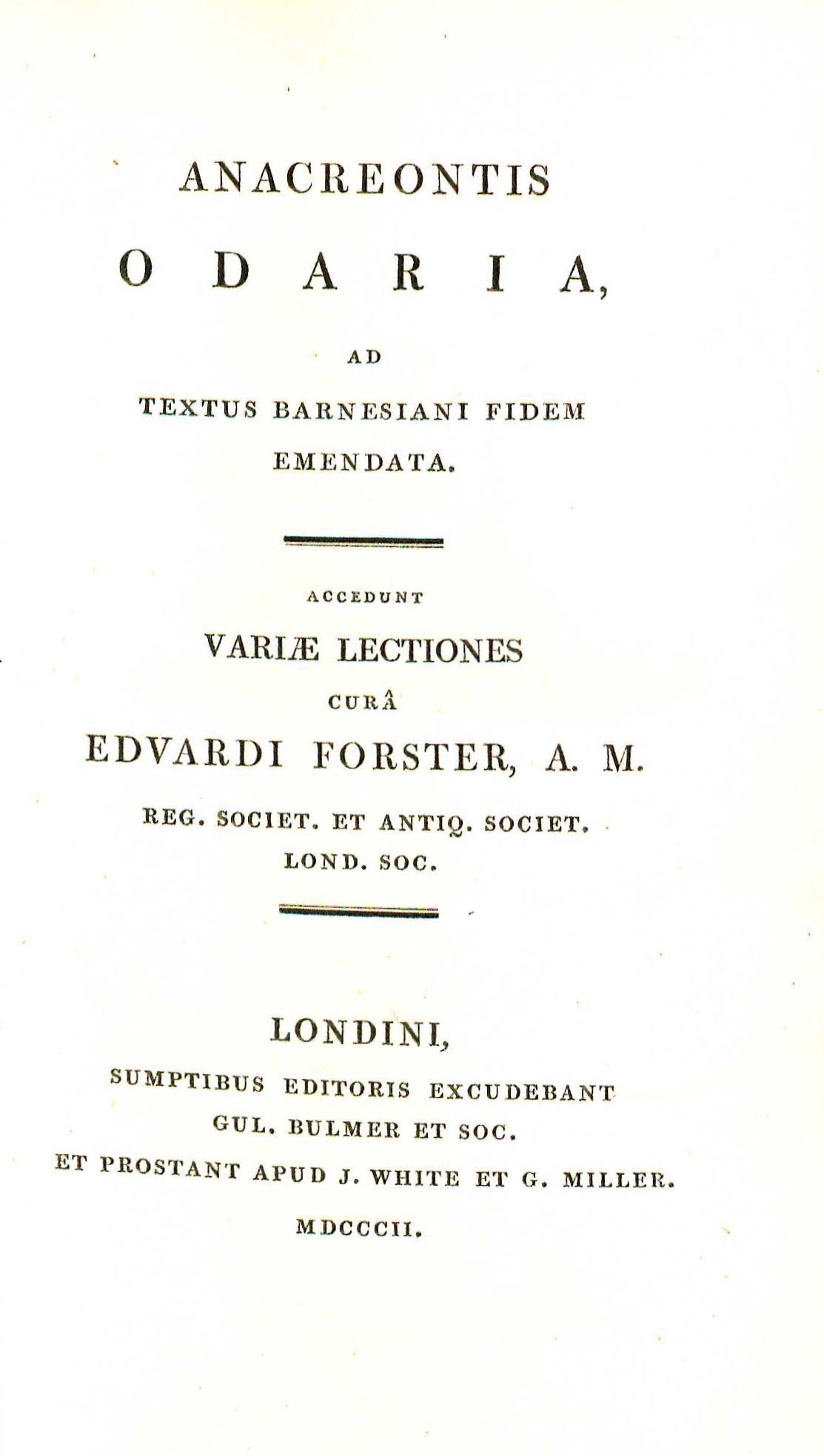

Title page from Anacreontis Odaria ad textus Barnesiani fidem emendata, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Published | Londini: Sumptibus editoris excudebant Gul. Bulmer et Soc. et prostant apud J. White et G. Miller |

| Date | 1802 |

| Language | Greek |

| Volumes | 1 volume set |

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in near contemporary full brown diced calf. Includes an early gift inscription from W. Haygarth to P. Leigh and the bookplate of Peter Issac.

View this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

External Links

References

- ↑ " Ana'creon” in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Marty Roth, “’Anacreon’ and Drink Poetry; or, the Art of Feeling Very Very Good,” Texas Studies in Literature and Language 42, no. 3 (Fall 2000): 314.

- ↑ "Anacreon" in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World, ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Roth, “’Anacreon’ and Drink Poetry; or, the Art of Feeling Very Very Good,” 316-17.

- ↑ Ibid at 317.