Difference between revisions of "Arithmetica Universalis"

m |

m |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

}}Sir Issac Newton (1642-1727) was a philosopher and mathematician who did not begin his educational studies immediately due to the need to help his mother raise his half sibilings. In 1661, Newton arrived in Cambridge to attend Trinity College, and entered as a sub-sizar where he performed menial tasks in order to stay enrolled and pay for his education. The ‘Quaestions quaedam’ launched Newton’s career into science.<ref>Richard S. Westfall, [http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.wm.edu/view/article/20059 "Newton, Sir Isaac (1642–1727)"] in ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed October 3, 2013.</ref><br /> | }}Sir Issac Newton (1642-1727) was a philosopher and mathematician who did not begin his educational studies immediately due to the need to help his mother raise his half sibilings. In 1661, Newton arrived in Cambridge to attend Trinity College, and entered as a sub-sizar where he performed menial tasks in order to stay enrolled and pay for his education. The ‘Quaestions quaedam’ launched Newton’s career into science.<ref>Richard S. Westfall, [http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.wm.edu/view/article/20059 "Newton, Sir Isaac (1642–1727)"] in ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed October 3, 2013.</ref><br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

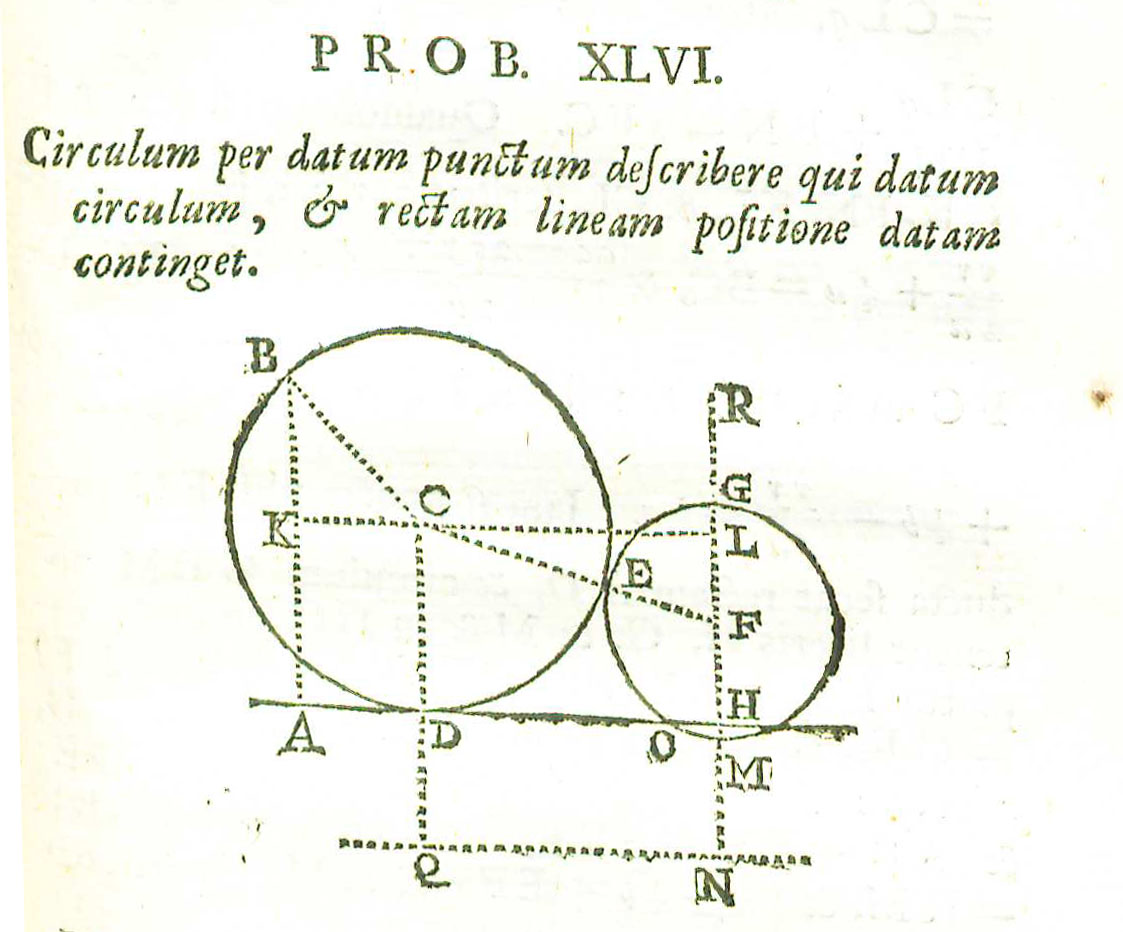

| − | [[File:NewtonArithmeticaUniversalisProblemXLVI1722.jpg|left|thumb|250px|<center>Problem XLVI ( | + | [[File:NewtonArithmeticaUniversalisProblemXLVI1722.jpg|left|thumb|250px|<center>Problem XLVI (page 189)</center>]] |

Newton did not begin to make his mathematical tracts available until after 1704. The manuscripts were originally made available to acolytes, who copied and translated them. However, many times, this ended up with Newton’s original theories being badly mutilated. It was due to the eventual increase in funding of scientific academies that Newtown finally allowed his works to go into print.<ref>Niccolo Guicciardini. "Issac Newton and the Publication of His Mathematical Manuscripts," ''Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, Part A'' 35, no. 3 (2004): 455-470.</ref> However, Newton maintained a scribe and public lecture mentality and most of his works did not go into print until after his death.<br /> | Newton did not begin to make his mathematical tracts available until after 1704. The manuscripts were originally made available to acolytes, who copied and translated them. However, many times, this ended up with Newton’s original theories being badly mutilated. It was due to the eventual increase in funding of scientific academies that Newtown finally allowed his works to go into print.<ref>Niccolo Guicciardini. "Issac Newton and the Publication of His Mathematical Manuscripts," ''Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, Part A'' 35, no. 3 (2004): 455-470.</ref> However, Newton maintained a scribe and public lecture mentality and most of his works did not go into print until after his death.<br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

| − | Listed in the [[Jefferson Inventory]] of [[Wythe's Library]] as ''Arithmetica Universalis Newtoni. 8vo.'' and given by [[Thomas Jefferson]] to his grandson [[Thomas Jefferson Randolph]]. The precise edition owned by Wythe is unknown. [http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe George Wythe's Library]<ref>''LibraryThing'', s. v. "Member: George Wythe, | + | Listed in the [[Jefferson Inventory]] of [[Wythe's Library]] as ''Arithmetica Universalis Newtoni. 8vo.'' and given by [[Thomas Jefferson]] to his grandson [[Thomas Jefferson Randolph]]. The precise edition owned by Wythe is unknown. [http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe George Wythe's Library]<ref>''LibraryThing'', s. v. [http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe "Member: George Wythe"], accessed on November 13, 2013, </ref> on LibraryThing indicates this, adding "Octavo editions in Latin were published at Cambridge/London in 1707 and London in 1722." The [https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433 Brown Bibliography]<ref> Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433</ref> lists the 2nd London edition. The Wolf Law Library followed Brown's suggestion and purchased the 1722 edition. |

==Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy== | ==Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy== | ||

Revision as of 16:39, 3 February 2014

Arithmetica Universalis: Sive De Compositione Et Resolutione Arithmetica Liber

by Sir Isaac Newton

| Arithmetica Universalis | |

|

Title page from Arithmetica Universalis, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Sir Isaac Newton |

| Published | London: Benji & Sam. Tooke |

| Date | 1722 |

| Edition | Editio secunda, in qua multa immutantur & emendantur, nonnulla adduntur |

| Language | Latin |

| Pages | 332 |

| Desc. | 8vo. (22 cm.) |

Sir Issac Newton (1642-1727) was a philosopher and mathematician who did not begin his educational studies immediately due to the need to help his mother raise his half sibilings. In 1661, Newton arrived in Cambridge to attend Trinity College, and entered as a sub-sizar where he performed menial tasks in order to stay enrolled and pay for his education. The ‘Quaestions quaedam’ launched Newton’s career into science.[1]

Newton did not begin to make his mathematical tracts available until after 1704. The manuscripts were originally made available to acolytes, who copied and translated them. However, many times, this ended up with Newton’s original theories being badly mutilated. It was due to the eventual increase in funding of scientific academies that Newtown finally allowed his works to go into print.[2] However, Newton maintained a scribe and public lecture mentality and most of his works did not go into print until after his death.

Based on lecture notes by Newton from the period 1673 to 1683, Arithmetica Universalis was first printed in Latin in Cambridge in 1707. In this work, Newton covers the essentials of algebra: notation, addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, extraction of roots, reduction of fractions, reduction of geometrical questions to equations, and resolution of equations. In addition, Newton extended Descartes' rule of signs to imaginary roots. He also formulated a rule to determine the number of imaginary roots of any equation.

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as Arithmetica Universalis Newtoni. 8vo. and given by Thomas Jefferson to his grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph. The precise edition owned by Wythe is unknown. George Wythe's Library[3] on LibraryThing indicates this, adding "Octavo editions in Latin were published at Cambridge/London in 1707 and London in 1722." The Brown Bibliography[4] lists the 2nd London edition. The Wolf Law Library followed Brown's suggestion and purchased the 1722 edition.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in contemporary paneled calf, expertly rebacked with red morocco label. Purchased from Ted Steinbock.

View this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

References

- ↑ Richard S. Westfall, "Newton, Sir Isaac (1642–1727)" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed October 3, 2013.

- ↑ Niccolo Guicciardini. "Issac Newton and the Publication of His Mathematical Manuscripts," Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, Part A 35, no. 3 (2004): 455-470.

- ↑ LibraryThing, s. v. "Member: George Wythe", accessed on November 13, 2013,

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433