Difference between revisions of "Pleasants v. Pleasants"

m (→External links) |

m |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE:''Pleasants v. Pleasants''}} | {{DISPLAYTITLE:''Pleasants v. Pleasants''}} | ||

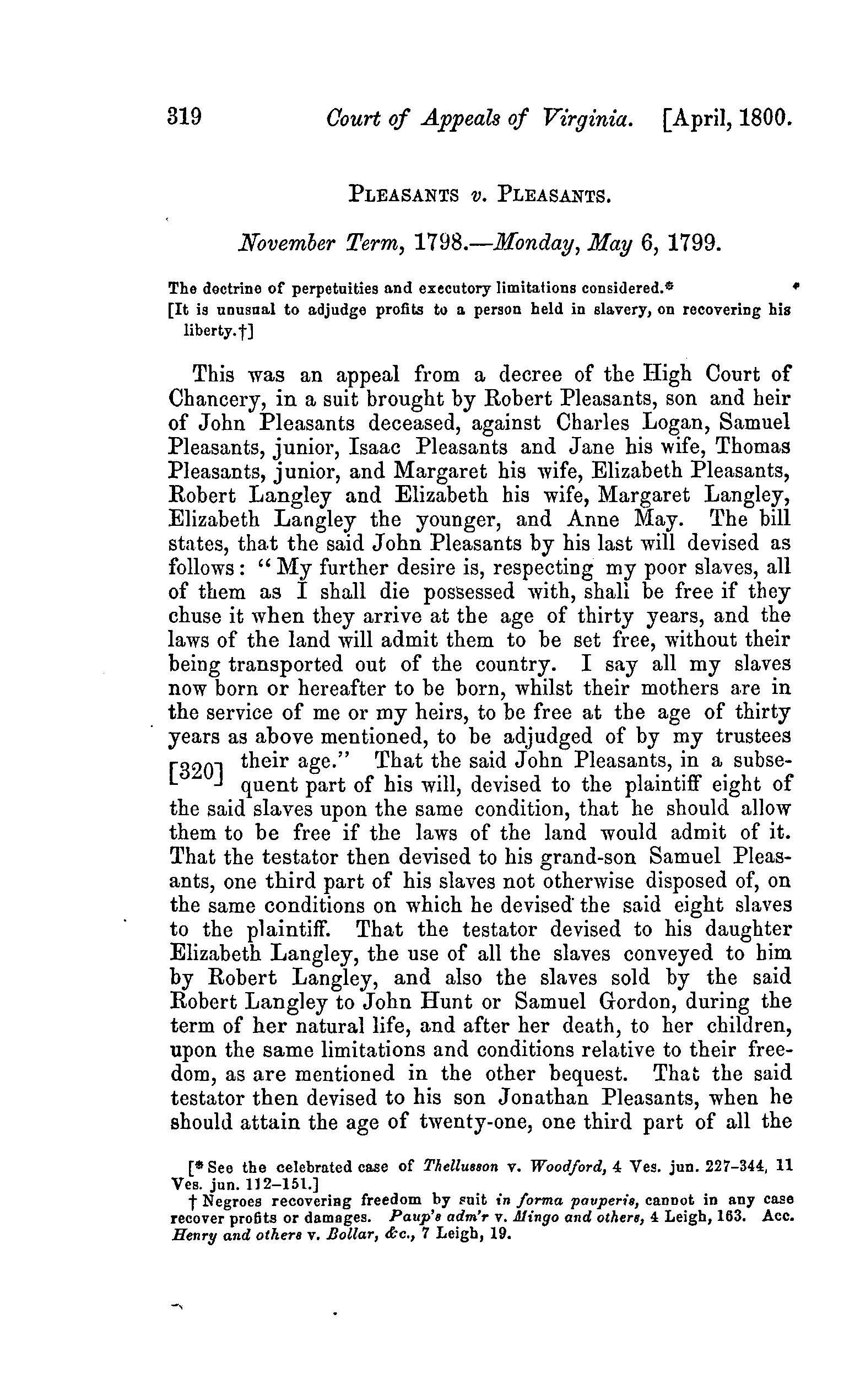

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:CallPleasantsvPleasants1854v2p319.jpg|link={{filepath:CallsReports1854V2PleasantsvPleasants.pdf}}|thumb|right|300px|First page of the opinion [[Media:CallsReports1854V2PleasantsvPleasants.pdf|''Pleasants v. Pleasants'']], in [https://wm.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/g9pr7p/alma991006014269703196 ''Reports of Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Court of Appeals of Virginia''], by Daniel Call. 3rd ed., ed. Lucian Minor. Richmond: A. Morris, 1854.]] |

| − | [[Media:CallsReports1854V2PleasantsvPleasants.pdf|''Pleasants v. Pleasants'']], 6 Va. (2 Call) 270 (1799),<ref>Daniel Call, ''Reports of Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Court of Appeals of Virginia,'' 3rd ed., ed. Lucian Minor (Richmond: A. Morris, 1854), 2:270. [[George Wythe]] owned the [[Reports of Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Court of Appeals of Virginia|first edition]] of this set.</ref> was a case | + | [[Media:CallsReports1854V2PleasantsvPleasants.pdf|''Pleasants v. Pleasants'']], 6 Va. (2 Call) 270 (1799),<ref>Daniel Call, ''Reports of Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Court of Appeals of Virginia,'' 3rd ed., ed. Lucian Minor (Richmond: A. Morris, 1854), 2:270. [[George Wythe]] owned the [[Reports of Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Court of Appeals of Virginia|first edition]] of this set.</ref> was a case in which the court considered whether the doctrine of perpetuities limited a testator's power to free, or manumit, slaves. |

| − | + | ||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| − | In his last will and testament, John | + | In his last will and testament, John Pleasants devised that |

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | all of [the slaves] as I shall die possessed with shall be free if they choose it when they arrive to the age of thirty years, and the laws of the land will admit them to be set free without their being transported out of the country. I say all my slaves now born or hereafter to be born, whilst their mothers are in the service of me or my heirs, to be free at the age of thirty years ...<ref>''The Edward Pleasants Valentine Papers, Abstracts of Records in the Local and General Archives of Virginia Relating to the Families of Allen, Bacon, Ballard, Batchelder...'', Edward Pleasants Valentine and Clayton Torrence, eds. (Richmond: Valentine Museum, 1927)2:1117.</ref> | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | Unfortunately, when Pleasants died in 1771 private manumission was illegal in Virginia.<ref>William Fernandez Hardin,"'This Unpleasant Business': Slavery, Law, and the Pleasants Family in Post-Revolutionary Virginia," ''Virginia Magazine of History and Biography'', 125:no.3 (), 212.</ref> Robert Pleasants, heir and executor of John Pleasant's estate, waited eleven years for the enactment of [https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/An_act_to_authorize_the_manumission_of_slaves_1782 "An Act to Authorize the Manumission of Slaves"] (1782). When his father's heirs did not readily comply with the terms of John Pleasant's will after the passage of the act, Robert applied to the Virginia General Assembly for the manumission of the slaves. However, the General Assembly believed this to be a matter that belonged in the courts. Robert brought the cause before the High Court of Chancery, though he was embarrassed to do so. At the time, slaves could not sue at common law. | ||

| + | |||

===The Court's Decision=== | ===The Court's Decision=== | ||

| − | Chancellor Wythe was of the opinion that the slaves who had already reached thirty or older when the act allowing for slaves to be free came into effect, were already entitled to their freedom. He further believed that those who were born before the | + | Chancellor Wythe was of the opinion that the slaves who had already reached thirty or older when the act allowing for slaves to be free came into effect, were already entitled to their freedom. He further believed that those who were born before the testator's death but had yet to reach the age of thirty, should attain their freedom once they reached that age. Finally, he thought the slaves who were born since the statute was enacted, were entitled to their freedom at birth. Wythe then decreed that the commissioner ascertain the ages of the slaves and take account of any profits they accrued since they gained their right to freedom. |

| + | |||

| + | The defendants appealed. The Appellate Court decreed that all slaves not subjected to creditor claims and where not above the age of 45 and their children born after the mother had already reached 30 years old were free. In addition, the court decreed that all slaves above 30 and under 45 years old were also free. Finally Court stated that all slaves under 30 and those born before their mother turned 30 were to continue as slaves until they reached the age of thirty and then they too would be free. When it came to calculating the work of the slaves since their freedom, the Court of Appeals overturned that portion of the decree. In his opinion, Judge Roane stated “There is yet one part of the Chancellor’s decree which I could have wished had not been made. I mean the reference to a commissioner to ascertain the profits of the slaves. We have no precedents, either of the Courts of England or this country, to guide use. In the former country, indeed, no such case could occur, because slavery is not there tolerated; and, in this country, I believe no instance can be produced of profits being adjudged to a person held in slavery, on recovering his liberty… I rejoice to be an [sic] humble organ of the law in decreeing liberty to the numerous appellees now before the court. And thus, upon grounds, as I suppose, of strict legal right, and not upon such grounds as, if sanctioned by the decision of this Court, might agitate and convulse the Commonwealth to its centre.” [p. 342-44] | ||

| + | |||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

*[[Wythe's Judicial Career]] | *[[Wythe's Judicial Career]] | ||

| Line 15: | Line 23: | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| + | *William Fernandez Hardin, [http://hdl.handle.net/1803/11711 "Litigating the Lash: Quaker Emancipator Robert Pleasants, the Law of Slavery and the Meaning of Manumission in Revolutionary and Early National Virginia,"] PhD diss., Vanderbilt University, 2013. | ||

| + | |||

*J. Max Weintraub, [http://www.vsb.org/docs/valawyermagazine/vl0417-letters.pdf "Robert Pleasants — Virginia's Forgotten Emancipator,"] ''Virginia Lawyer'' 65 (April 2017), 6-7. | *J. Max Weintraub, [http://www.vsb.org/docs/valawyermagazine/vl0417-letters.pdf "Robert Pleasants — Virginia's Forgotten Emancipator,"] ''Virginia Lawyer'' 65 (April 2017), 6-7. | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

| − | [[Category: Cases]] [[Category: Slavery]] | + | [[Category: Cases]] |

| + | [[Category: Inheritance]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Slavery]] | ||

Latest revision as of 13:20, 7 September 2023

Pleasants v. Pleasants, 6 Va. (2 Call) 270 (1799),[1] was a case in which the court considered whether the doctrine of perpetuities limited a testator's power to free, or manumit, slaves.

Background

In his last will and testament, John Pleasants devised that

all of [the slaves] as I shall die possessed with shall be free if they choose it when they arrive to the age of thirty years, and the laws of the land will admit them to be set free without their being transported out of the country. I say all my slaves now born or hereafter to be born, whilst their mothers are in the service of me or my heirs, to be free at the age of thirty years ...[2]

Unfortunately, when Pleasants died in 1771 private manumission was illegal in Virginia.[3] Robert Pleasants, heir and executor of John Pleasant's estate, waited eleven years for the enactment of "An Act to Authorize the Manumission of Slaves" (1782). When his father's heirs did not readily comply with the terms of John Pleasant's will after the passage of the act, Robert applied to the Virginia General Assembly for the manumission of the slaves. However, the General Assembly believed this to be a matter that belonged in the courts. Robert brought the cause before the High Court of Chancery, though he was embarrassed to do so. At the time, slaves could not sue at common law.

The Court's Decision

Chancellor Wythe was of the opinion that the slaves who had already reached thirty or older when the act allowing for slaves to be free came into effect, were already entitled to their freedom. He further believed that those who were born before the testator's death but had yet to reach the age of thirty, should attain their freedom once they reached that age. Finally, he thought the slaves who were born since the statute was enacted, were entitled to their freedom at birth. Wythe then decreed that the commissioner ascertain the ages of the slaves and take account of any profits they accrued since they gained their right to freedom.

The defendants appealed. The Appellate Court decreed that all slaves not subjected to creditor claims and where not above the age of 45 and their children born after the mother had already reached 30 years old were free. In addition, the court decreed that all slaves above 30 and under 45 years old were also free. Finally Court stated that all slaves under 30 and those born before their mother turned 30 were to continue as slaves until they reached the age of thirty and then they too would be free. When it came to calculating the work of the slaves since their freedom, the Court of Appeals overturned that portion of the decree. In his opinion, Judge Roane stated “There is yet one part of the Chancellor’s decree which I could have wished had not been made. I mean the reference to a commissioner to ascertain the profits of the slaves. We have no precedents, either of the Courts of England or this country, to guide use. In the former country, indeed, no such case could occur, because slavery is not there tolerated; and, in this country, I believe no instance can be produced of profits being adjudged to a person held in slavery, on recovering his liberty… I rejoice to be an [sic] humble organ of the law in decreeing liberty to the numerous appellees now before the court. And thus, upon grounds, as I suppose, of strict legal right, and not upon such grounds as, if sanctioned by the decision of this Court, might agitate and convulse the Commonwealth to its centre.” [p. 342-44]

See also

References

- ↑ Daniel Call, Reports of Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Court of Appeals of Virginia, 3rd ed., ed. Lucian Minor (Richmond: A. Morris, 1854), 2:270. George Wythe owned the first edition of this set.

- ↑ The Edward Pleasants Valentine Papers, Abstracts of Records in the Local and General Archives of Virginia Relating to the Families of Allen, Bacon, Ballard, Batchelder..., Edward Pleasants Valentine and Clayton Torrence, eds. (Richmond: Valentine Museum, 1927)2:1117.

- ↑ William Fernandez Hardin,"'This Unpleasant Business': Slavery, Law, and the Pleasants Family in Post-Revolutionary Virginia," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 125:no.3 (), 212.

External links

- William Fernandez Hardin, "Litigating the Lash: Quaker Emancipator Robert Pleasants, the Law of Slavery and the Meaning of Manumission in Revolutionary and Early National Virginia," PhD diss., Vanderbilt University, 2013.

- J. Max Weintraub, "Robert Pleasants — Virginia's Forgotten Emancipator," Virginia Lawyer 65 (April 2017), 6-7.