Difference between revisions of "Shermer v. Richardson"

m |

m (→The Court's Decision) |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE:''Shermer v. Richardson''}} | {{DISPLAYTITLE:''Shermer v. Richardson''}} | ||

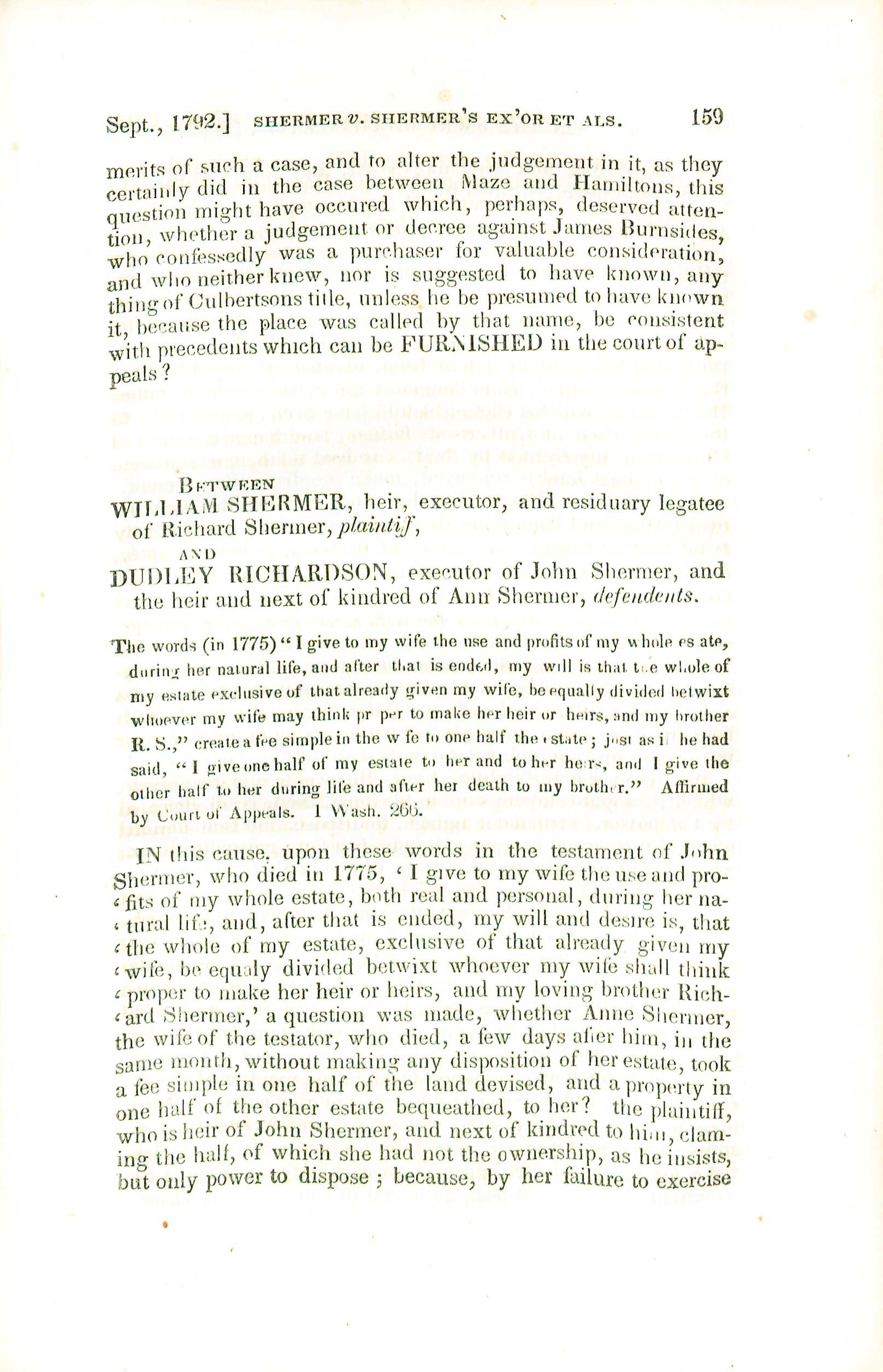

| − | [[File:WytheShermerVRichardson1852.jpg|link= | + | [[File:WytheShermerVRichardson1852.jpg|link={{filepath:WytheDecisions1852ShermerVRichardson.pdf}}|thumb|right|300px|First page of the opinion [[Media:WytheDecisions1852ShermerVRichardson.pdf|''Shermer v. Richardson'']], in [https://wm.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/g9pr7p/alma991006014269703196 ''Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery''], by George Wythe. 2nd ed. Richmond: J. W. Randolph, 1852.]] |

[[Media:WytheDecisions1852ShermerVRichardson.pdf|''Shermer v. Richardson'']], Wythe 159 (1792),<ref>George Wythe, ''[[Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery (1852)|Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions]],'' 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852), 159.</ref> discussed whether a will's language had given the deceased person's wife the right to property in full or just the right to designate who the property went to. | [[Media:WytheDecisions1852ShermerVRichardson.pdf|''Shermer v. Richardson'']], Wythe 159 (1792),<ref>George Wythe, ''[[Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery (1852)|Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions]],'' 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852), 159.</ref> discussed whether a will's language had given the deceased person's wife the right to property in full or just the right to designate who the property went to. | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

The Chancery Court dismissed William Shermer's request. | The Chancery Court dismissed William Shermer's request. | ||

| − | Wythe noted that according to the very first section of Lyttleton's Tenures, a transfer of property rights must include the words "and to his heirs" to award rights in fee simple, the property right which can be inherited.<ref>Sir Thomas Littleton, Littletons Tenures in English sec. 1 (London : Printed for the Companie of Stationers, 1612).</ref> Those words, however, do not force a person to leave that property to their legal heirs. A person can prevent their legal heirs from inheriting property by selling it during the person's lifetime or by designating someone else in their will to inherit the property. All that the words "and to his heirs" do is explain who gets the property if the person dies without designating the next owner. | + | Wythe noted that according to the very first section of [[Tenures de Monsieur Littleton|Lyttleton's Tenures]], a transfer of property rights must include the words "and to his heirs" to award rights in fee simple, the property right which can be inherited.<ref>Sir Thomas Littleton, Littletons Tenures in English sec. 1 (London : Printed for the Companie of Stationers, 1612).</ref> Those words, however, do not force a person to leave that property to their legal heirs. A person can prevent their legal heirs from inheriting property by selling it during the person's lifetime or by designating someone else in their will to inherit the property. All that the words "and to his heirs" do is explain who gets the property if the person dies without designating the next owner. |

When it comes to a will, Wythe added, the words "and to his heirs" are not even necessary to give someone title in fee simple. Simply "giving" property to someone in a will without further clarifying language implies that the deceased person also wanted the property to go "to his heirs". [[Third Part of the Institutes of the Laws of England|Sir Edward Coke]]<ref>Sir Edward Coke, The First Part of the Institutes of the Laws of England (London: M. Flesher, for W. Lee, and D. Pakeman, 1644): fol. 9b.</ref> and other authorities agree on this. | When it comes to a will, Wythe added, the words "and to his heirs" are not even necessary to give someone title in fee simple. Simply "giving" property to someone in a will without further clarifying language implies that the deceased person also wanted the property to go "to his heirs". [[Third Part of the Institutes of the Laws of England|Sir Edward Coke]]<ref>Sir Edward Coke, The First Part of the Institutes of the Laws of England (London: M. Flesher, for W. Lee, and D. Pakeman, 1644): fol. 9b.</ref> and other authorities agree on this. | ||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

[[Category:Cases]] | [[Category:Cases]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Inheritance]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:08, 16 June 2023

Shermer v. Richardson, Wythe 159 (1792),[1] discussed whether a will's language had given the deceased person's wife the right to property in full or just the right to designate who the property went to.

Background

John Shermer died in 1775. His will said "I give to my wife (Anne) the use and profits of my whole estate, both real and personal, during her natural life, and, after that is ended, my will and desire is, that the whole of my estate, exclusive of that already given my wife, be equaly divided betwixt whoever my wife shall think proper to make her heir or heirs, and my loving brother Richard Shermer". Anne died a few days after John without designating anyone to inherit her estate.

The plaintiff, William Shermer, was executor of Richard Shermer's estate and John's and Richard's legal heir.[2] William filed a bill with the High Court of Chancery asking it to award him John's entire estate. William argued that John's will only gave Anne the right to designate an heir for half of John's estate instead of transferring ownership of that half to Anne. Because Anne did not designate an heir before she died, William said that her half of John's estate was legally unassigned to anyone, and therefore should go to John's closest living heir, William.

The defendant, Dudley Richardson, was executor of John Shermer's estate and Anne Shermer's next of kin and heir.

The Court's Decision

The Chancery Court dismissed William Shermer's request.

Wythe noted that according to the very first section of Lyttleton's Tenures, a transfer of property rights must include the words "and to his heirs" to award rights in fee simple, the property right which can be inherited.[3] Those words, however, do not force a person to leave that property to their legal heirs. A person can prevent their legal heirs from inheriting property by selling it during the person's lifetime or by designating someone else in their will to inherit the property. All that the words "and to his heirs" do is explain who gets the property if the person dies without designating the next owner.

When it comes to a will, Wythe added, the words "and to his heirs" are not even necessary to give someone title in fee simple. Simply "giving" property to someone in a will without further clarifying language implies that the deceased person also wanted the property to go "to his heirs". Sir Edward Coke[4] and other authorities agree on this.

In this case, then, Wythe said that giving Anne half of the estate to Anne and "whoever (she) shall think proper to make her heir" gave her the property in fee simple. John's intent in this case was clear: he wanted to give half of his estate to Anne to dispose of as she wished. John's words may have been poorly chosen, but the Chancery Court will read in the language needed to carry out his intent. Since Anne received half of the property in fee simple, that property should go to her heir, Dudley Richardson, because Anne did not designate someone specific to inherit it after her death.

While it is true that John also gave Anne a life estate[5] in all his property, Wythe said that John's award to Anne in fee simple trumps the life estate — Wythe cites to Coke again for this idea.[6]

So, in the end, Wythe interpreted John's will to mean that John wanted Anne to have one-half of his whole estate in fee simple. The other half of John's estate would go in a life estate to Anne, then to Richard Shermer in fee simple after Anne died.

William Shermer appealed to the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals, which affirmed Wythe's decree.[7]

Works Cited or Referenced by Wythe

Thomas Lyttleton's, Les Tenures de Monsieur Littleton: ouesque certain cases addes per auters de puisne temps, qu[eu]x cases vo[us] troueres signes ouesq[ue] cest signe...

Citation in Wythe's opinion:

"By the first section of Lyttleton's Tenures we can learn, that, in feoffments and grant, a fee simple, or the greatest property, in land is not conveyed to the taker, unless in habendum after his name be inserted the words. 'and to the heirs.'[8]

References

- ↑ George Wythe, Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852), 159.

- ↑ Someone who would inherit John's and Richard's property that they had not specifically designated in a will to go to someone else.

- ↑ Sir Thomas Littleton, Littletons Tenures in English sec. 1 (London : Printed for the Companie of Stationers, 1612).

- ↑ Sir Edward Coke, The First Part of the Institutes of the Laws of England (London: M. Flesher, for W. Lee, and D. Pakeman, 1644): fol. 9b.

- ↑ Sort of like a trust, a person who has a life estate only gets use of the property during their lifetime. After the person who holds the life estate interest in a property dies, the property's ownership reverts to the person who gave away the life estate.

- ↑ Sir Edward Coke, The First Part of the Institutes of the Laws of England (London: M. Flesher, for W. Lee, and D. Pakeman, 1644): fol. 22b.

- ↑ Shermer v. Shermer's Executors, 1 Va. (1 Wash.) 266 (1794).

- ↑ Wythe, 160