Difference between revisions of "Platonos Hapanta ta Sozomena"

m (→Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library) |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

|commontitle= | |commontitle= | ||

|vol= | |vol= | ||

| − | |author=Plato | + | |author=[[:Category:Plato|Plato]] |

|editor= | |editor= | ||

|trans= | |trans= | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

|pages= | |pages= | ||

|desc= | |desc= | ||

| − | }} | + | }}Little is known of Greek philosopher [[wikipedia:Plato|Plato's]] (429 – 347 B.C.E.) early years, but he was interested in politics in his youth, and studied rhetoric under Dionysius.<ref>George Boas, "Fact and Legend in the Biography of Plato," ''The Philosophical Review'' 57, no. 5 (Duke University Press, 1948): 443-44.</ref> He became a disciple of [[wikipedia:Socrates|Socrates]], and most of Plato's works are in the form of a dialogue, many of which feature Socrates questioning various philosophical doctrines.<ref>Richard Kraut, ed., ''The Cambridge Companion to Plato'', (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992): 3.</ref> Plato introduced the Western conception of philosophy as a method of thought that probes the boundaries of human senses and understanding of the world.<ref>Ibid, 1.</ref> |

| + | Plato's philosophy centered on the doctrine that there are eternal forms that exist, such as "beauty" or "good," which human senses cannot fully understand but strive to attain.<ref>Richard Kraut, Edward N. Zalta, ed., "Plato," ''The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' (Fall 2013).</ref> His works do not present a comprehensive system of thought, but instead stimulate discussion and present starting points on how one may question the world.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Plato believed that a philosopher should probe why he perceives the world the way he does, and should apply overarching contemplative ideas (his eternal "forms") in the moral actions of man.<ref>Alcinous, "The Doctrines of Plato", translated by George Burges in ''The Works of Plato: a new and literal version'' (London: 1865), VI: 241-43.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Plato developed this moral theory throughout his works. For example, in the ''Republic'' he explored how to attain happiness by living virtuously.<ref> Mary Margaret Mackenzie, "Plato's Moral Theory," ''Journal of Medical Ethics'' 11, no. 2 (BMJ, 1985):88, 90.</ref> He continuously criticizes social values and political institutions in works including ''Protagoras'', ''Gorgias'', ''Euthydemus'', proving his work is grounded in the practical sphere of human life as well as concerned with the soul.<ref>Richard Kraut, "Plato."</ref> | ||

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

| − | + | Listed in the [[Jefferson Inventory]] of [[Wythe's Library]] as "Platonis opera. Gr. Lat. fol." and given by [[Thomas Jefferson]] to his son-in-law, [[Thomas Mann Randolph]]. Later appears on Randolph's 1832 estate inventory as "Plato's Works (Greek) 1 [vol.], $10.00." We do not have enough information to conclusively identify which edition Wythe owned. [http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe George Wythe's Library]<ref>''LibraryThing'', s.v. "[http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe Member: George Wythe]," accessed on July 17, 2023.</ref> on LibraryThing indicates this. The [https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433 Brown Bibliography]<ref>Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433.</ref> suggests the 1578, 3 volume set (translated by Jean de Serres and edited by Henri Estienne) published in Geneva based on the copy Thomas Jefferson sold to the Library of Congress in 1815.<ref>E. Millicent Sowerby, ''Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson'', (Washington, D.C.: The Library of Congress, 1952-1959), 2:32-33 [https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015033648109&view=1up&seq=44 [no.1309]].</ref> | |

| + | |||

| + | As yet, the Wolf Law Library has not found an appropriate copy of Plato's works in Greek and Latin. | ||

| + | |||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

*[[Jefferson Inventory]] | *[[Jefferson Inventory]] | ||

| Line 30: | Line 36: | ||

[[Category:Philosophy]] | [[Category:Philosophy]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Plato]] | ||

[[Category:Thomas Mann Randolph's Books]] | [[Category:Thomas Mann Randolph's Books]] | ||

[[Category:Titles in Wythe's Library]] | [[Category:Titles in Wythe's Library]] | ||

Latest revision as of 10:06, 18 July 2023

by Plato

| Platonis Opera Quae Extant Omnia | ||

|

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | Plato | |

| Date | Precise edition unknown | |

Little is known of Greek philosopher Plato's (429 – 347 B.C.E.) early years, but he was interested in politics in his youth, and studied rhetoric under Dionysius.[1] He became a disciple of Socrates, and most of Plato's works are in the form of a dialogue, many of which feature Socrates questioning various philosophical doctrines.[2] Plato introduced the Western conception of philosophy as a method of thought that probes the boundaries of human senses and understanding of the world.[3]

Plato's philosophy centered on the doctrine that there are eternal forms that exist, such as "beauty" or "good," which human senses cannot fully understand but strive to attain.[4] His works do not present a comprehensive system of thought, but instead stimulate discussion and present starting points on how one may question the world.[5] Plato believed that a philosopher should probe why he perceives the world the way he does, and should apply overarching contemplative ideas (his eternal "forms") in the moral actions of man.[6]

Plato developed this moral theory throughout his works. For example, in the Republic he explored how to attain happiness by living virtuously.[7] He continuously criticizes social values and political institutions in works including Protagoras, Gorgias, Euthydemus, proving his work is grounded in the practical sphere of human life as well as concerned with the soul.[8]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

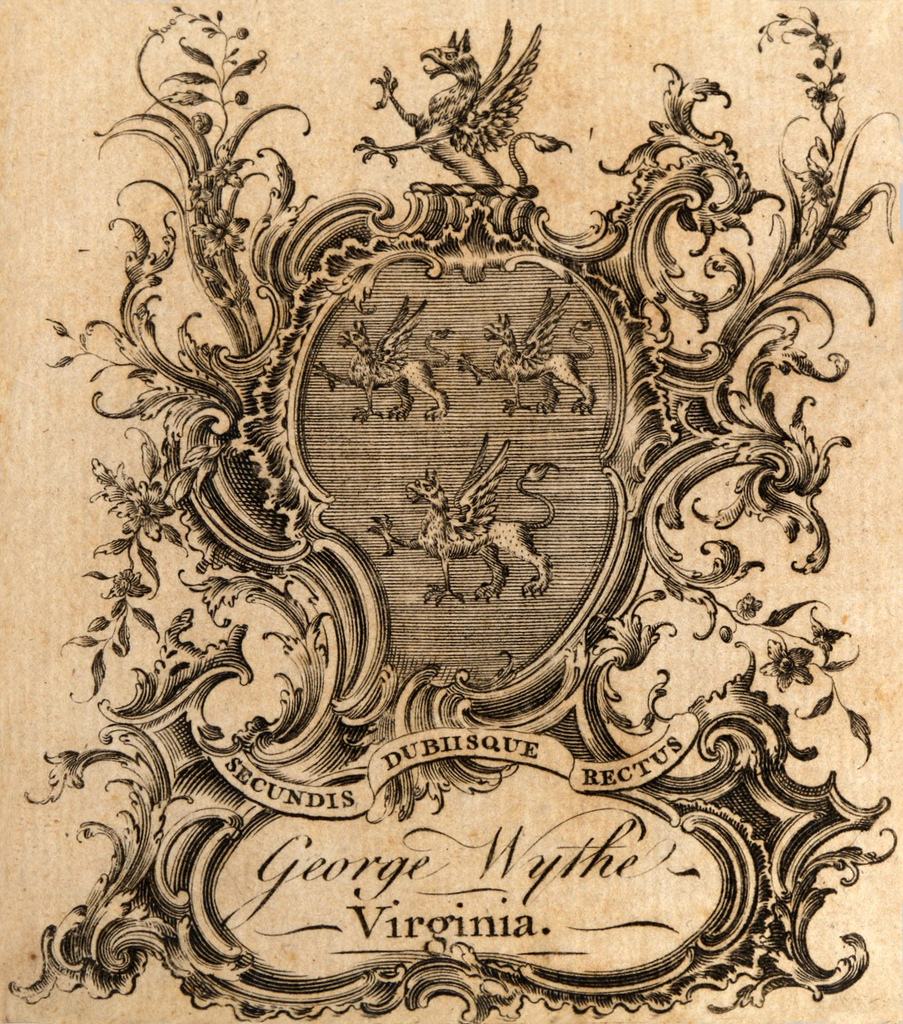

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as "Platonis opera. Gr. Lat. fol." and given by Thomas Jefferson to his son-in-law, Thomas Mann Randolph. Later appears on Randolph's 1832 estate inventory as "Plato's Works (Greek) 1 [vol.], $10.00." We do not have enough information to conclusively identify which edition Wythe owned. George Wythe's Library[9] on LibraryThing indicates this. The Brown Bibliography[10] suggests the 1578, 3 volume set (translated by Jean de Serres and edited by Henri Estienne) published in Geneva based on the copy Thomas Jefferson sold to the Library of Congress in 1815.[11]

As yet, the Wolf Law Library has not found an appropriate copy of Plato's works in Greek and Latin.

See also

References

- ↑ George Boas, "Fact and Legend in the Biography of Plato," The Philosophical Review 57, no. 5 (Duke University Press, 1948): 443-44.

- ↑ Richard Kraut, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Plato, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992): 3.

- ↑ Ibid, 1.

- ↑ Richard Kraut, Edward N. Zalta, ed., "Plato," The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2013).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Alcinous, "The Doctrines of Plato", translated by George Burges in The Works of Plato: a new and literal version (London: 1865), VI: 241-43.

- ↑ Mary Margaret Mackenzie, "Plato's Moral Theory," Journal of Medical Ethics 11, no. 2 (BMJ, 1985):88, 90.

- ↑ Richard Kraut, "Plato."

- ↑ LibraryThing, s.v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on July 17, 2023.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433.

- ↑ E. Millicent Sowerby, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, (Washington, D.C.: The Library of Congress, 1952-1959), 2:32-33 [no.1309].