Difference between revisions of "Appendix to the Notes on Virginia"

m |

|||

| (16 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE:''An Appendix to the Notes on Virginia Relative to the Murder of Logan's Family''}} | {{DISPLAYTITLE:''An Appendix to the Notes on Virginia Relative to the Murder of Logan's Family''}} | ||

===by Thomas Jefferson=== | ===by Thomas Jefferson=== | ||

| − | |||

{{NoBookInfoBox | {{NoBookInfoBox | ||

|shorttitle=Appendix to the Notes on Virginia | |shorttitle=Appendix to the Notes on Virginia | ||

|commontitle= | |commontitle= | ||

|vol= | |vol= | ||

| − | |author=Thomas Jefferson | + | |author=[[:Category:Thomas Jefferson|Thomas Jefferson]] |

|editor= | |editor= | ||

|trans= | |trans= | ||

| − | |publoc= | + | |publoc=[[:Category:Philadelphia|Philadelphia]] |

| − | |publisher= | + | |publisher=S.H. Smith |

|year=1800 | |year=1800 | ||

|edition= | |edition= | ||

| − | |lang= | + | |lang=[[:Category:English|English]] |

|set= | |set= | ||

|pages= | |pages= | ||

|desc= | |desc= | ||

| − | }} | + | }}In his ''[[Notes on the State of Virginia]]'', author [[Thomas Jefferson]] included a 1774 story about a band of white Virginians led by [[wikipedia:Michael Cresap|Michael Cresap]] that sought revenge for an Indian attack upon a neighbor and instead massacred an innocent Indian family. [[wikipedia:Logan (American Indian leader)|Logan]], a Mingo chief, claimed that family to be his own and wrote a speech regarding the massacre for the treaty meeting at the close of [[wikipedia:Lord Dunmore's War|Dunmore's War]].<ref>Thomas Jefferson, ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=UO0OAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover Notes on the State of Virginia]'' (London: John Stockdale, Opposite Burlington-House, Piccadilly, 1787), 104-05.</ref> Jefferson detailed Logan's speech, addressed to [[wikipedia:John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore|Lord Dunmore]], as: |

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | I appeal to any white man to say, if ever he entered Logan's cabin hungry, and he gave him not meat; if ever he came cold and naked, and he clothed him not. During the course of the last long and bloody war, Logan remained idle in his cabin, an advocate for peace. Such was my love for the whites, that my countrymen pointed as they passed, and said, 'Logan is the friend of white men.' I had even thought to have lived with you, but for the injuries of one man. Col. Cresap, the last spring, in cold blood, and unprovoked, murdered all the relations of Logan, not sparing even my women and children. There runs not a drop of my blood in the veins of any living creature. This called on me for revenge. I have sought it: I have killed many: I have fully glutted my vengeance. For my country, I rejoice at the beams of peace. But do not harbour a thought that mine is the joy of fear. Logan never felt fear. He will not turn on his heel to save his life. Who is there to mourn for Logan?—Not one.<ref>Jefferson, ''Notes'', 105-06.</ref> | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | When Lord Dunmore's officers returned from the war, word of Logan's speech spread quickly, with Jefferson describing the speech as "the theme of every conversation" and noting that local newspapers published transcripts of the speech.<ref>Thomas Jefferson, ''[https://archive.org/details/appendixtonoteso00jeff An Appendix to the Notes on Virginia Relative to the Murder of Logan's Family]'' (Philadelphia: S.H. Smith, 1800), 4.</ref> However, in 1782, Jefferson's own publication of Logan's speech in ''Notes on Virginia'' immediately garnered attention, especially for his retelling of the circumstances surrounding the alleged murder of Chief Logan's family. Jefferson acknowledged that his passage on Logan's speech had "excited some newspaper publications" with doubts of the truth in Jefferson's story of Chief Logan and Colonel Cresap.<ref>Ibid., 3.</ref> Jefferson defended his publication of Logan's speech, stating that the speech he published was "only repeated in the ''Notes on Virginia'' precisely as it had been current more than a dozen years before they were published," thus concurring with "thousands and thousands of others in believing a transaction on authority which merited respect."<ref>Ibid., 4.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1800, Jefferson later published ''An Appendix to the Notes on Virginia Relative to the Murder of Logan's Family'' as an "answer to the charge that [he] had invented the narrative in the Notes to cover up the alleged literary imposture of Logan's speech."<ref>Thomas Warren Field, ''An Essay Towards an Indian Bibliography: Being a Catalogue of Books, Relating to the History, Antiquities, Languages, Customs, Religion, Wars, Literature, and Origin of the American Indians, in the Library of Thomas W. Field; with Bibliographical and Historical Notes, and Synopses of the Contents of Some of the Works Least Known'' (New York: Scribner, Armstrong, and Co., 1873), 190.</ref> The appendix contained letters, certificates, and depositions that supported Jefferson's telling of the Logan-Cresap saga, aiming to prove that Logan did give the speech as transcribed and that Cresap did lead the massacre as accused.<ref>"American Review," ''The Monthly Magazine and American Review'' 3, no. 1 (July 1800): 51.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | More modern analyses of the story behind Chief Logan's speech have continued to doubt the accuracy of Jefferson's retelling. Critics accused Jefferson of promoting Logan's eloquence as a speaker, when in fact Logan never publicly delivered the speech. Instead, Logan sent a message that contained his speech to Lord Dunmore, and Logan never attended the treaty meeting himself.<ref>Edward D. Seeber, "Critical Views on Logan's Speech," ''The Journal of American Folklore'' 60, no. 236 (1947): 137.</ref> Cresap's involvement in the massacre had been denied as well, and Jefferson was accused of perpetuating an assumption of guilt against Cresap. Further, other critics had pointed to evidence the none of Logan’s children had died in the massacres of 1774, and that the Indians murdered were not, in fact, Logan’s immediate family.<ref>Ibid., 134.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Regardless of its origin, Logan's speech had a lasting effect on American culture. Still relevant well into the nineteenth century, the speech was praised for having "mingled pride, courage, and sorrow" and subsequently "elevated the character of the native American throughout the intelligent world."<ref>Charles Whittlesey, ''Fugitive Essays, Upon Interesting and Useful Subjects, Relating to the Early History of Ohio: Its Geology and Agriculture, with a Biography of the First Successful Constructor of Steamboats; A Dissertation upon the Antiquity of the Material Universe, and Other Articles, Being a Reprint from Various Periodicals of the Day'' (Hudson, OH: Sawyer, Ingersoll and Co., 1852), 145.</ref> Theodore Roosevelt even wrote that the speech was "perhaps the finest outburst of savage eloquence of which we have any authentic record."<ref>Theodore Roosevelt, ''The Winning of the West'', vol. 1, ''From the Alleghanies to the Mississippi'' (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1889), 237.</ref> | ||

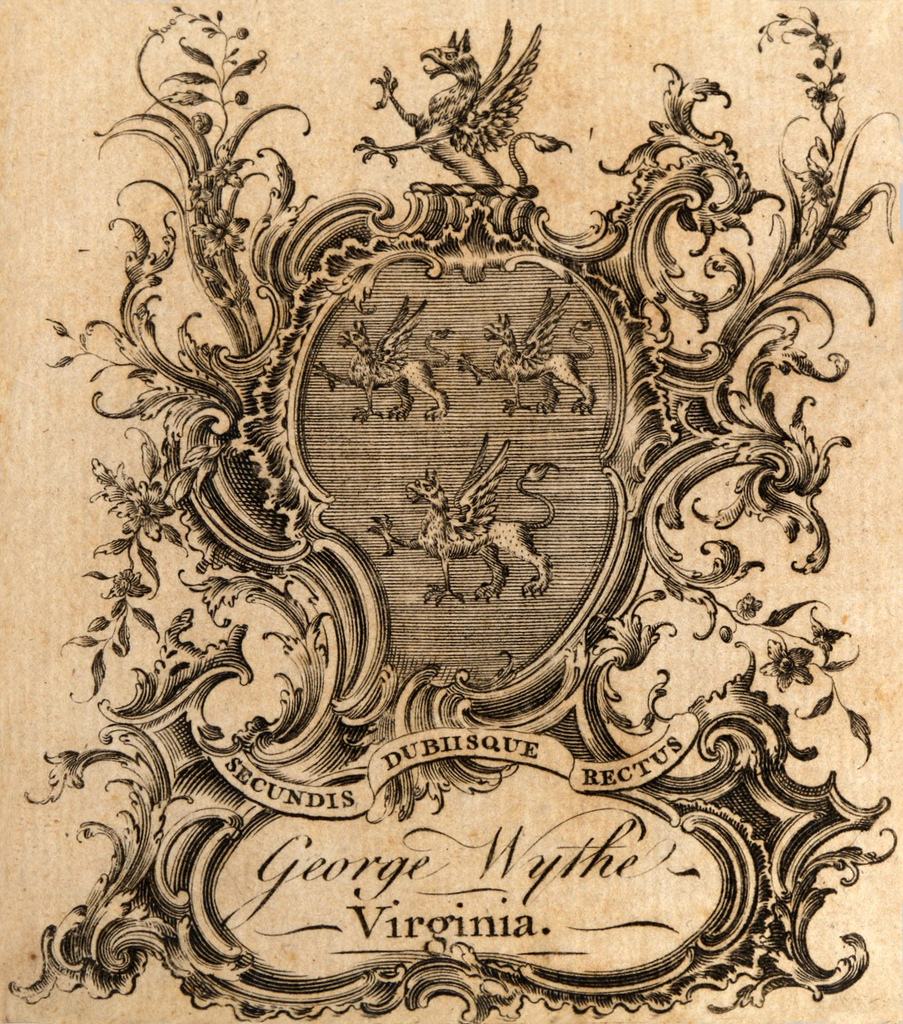

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==See also== | ||

| + | *''[[Manual of Parliamentary Practice|A Manual of Parliamentary Practice for the Use of the Senate of the United States]]'' | ||

| + | *''[[Notes on the State of Virginia]]'' | ||

| + | *[[Thomas Jefferson]] | ||

| + | *[[Wythe's Library]] | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 25: | Line 42: | ||

[[Category:American History]] | [[Category:American History]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Thomas Jefferson]] | ||

[[Category:Titles in Wythe's Library]] | [[Category:Titles in Wythe's Library]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:English]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Philadelphia]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | __NOTOC__ | ||

Latest revision as of 14:13, 14 September 2020

by Thomas Jefferson

| Appendix to the Notes on Virginia | ||

|

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | Thomas Jefferson | |

| Published | Philadelphia: S.H. Smith | |

| Date | 1800 | |

| Language | English | |

In his Notes on the State of Virginia, author Thomas Jefferson included a 1774 story about a band of white Virginians led by Michael Cresap that sought revenge for an Indian attack upon a neighbor and instead massacred an innocent Indian family. Logan, a Mingo chief, claimed that family to be his own and wrote a speech regarding the massacre for the treaty meeting at the close of Dunmore's War.[1] Jefferson detailed Logan's speech, addressed to Lord Dunmore, as:

I appeal to any white man to say, if ever he entered Logan's cabin hungry, and he gave him not meat; if ever he came cold and naked, and he clothed him not. During the course of the last long and bloody war, Logan remained idle in his cabin, an advocate for peace. Such was my love for the whites, that my countrymen pointed as they passed, and said, 'Logan is the friend of white men.' I had even thought to have lived with you, but for the injuries of one man. Col. Cresap, the last spring, in cold blood, and unprovoked, murdered all the relations of Logan, not sparing even my women and children. There runs not a drop of my blood in the veins of any living creature. This called on me for revenge. I have sought it: I have killed many: I have fully glutted my vengeance. For my country, I rejoice at the beams of peace. But do not harbour a thought that mine is the joy of fear. Logan never felt fear. He will not turn on his heel to save his life. Who is there to mourn for Logan?—Not one.[2]

When Lord Dunmore's officers returned from the war, word of Logan's speech spread quickly, with Jefferson describing the speech as "the theme of every conversation" and noting that local newspapers published transcripts of the speech.[3] However, in 1782, Jefferson's own publication of Logan's speech in Notes on Virginia immediately garnered attention, especially for his retelling of the circumstances surrounding the alleged murder of Chief Logan's family. Jefferson acknowledged that his passage on Logan's speech had "excited some newspaper publications" with doubts of the truth in Jefferson's story of Chief Logan and Colonel Cresap.[4] Jefferson defended his publication of Logan's speech, stating that the speech he published was "only repeated in the Notes on Virginia precisely as it had been current more than a dozen years before they were published," thus concurring with "thousands and thousands of others in believing a transaction on authority which merited respect."[5]

In 1800, Jefferson later published An Appendix to the Notes on Virginia Relative to the Murder of Logan's Family as an "answer to the charge that [he] had invented the narrative in the Notes to cover up the alleged literary imposture of Logan's speech."[6] The appendix contained letters, certificates, and depositions that supported Jefferson's telling of the Logan-Cresap saga, aiming to prove that Logan did give the speech as transcribed and that Cresap did lead the massacre as accused.[7]

More modern analyses of the story behind Chief Logan's speech have continued to doubt the accuracy of Jefferson's retelling. Critics accused Jefferson of promoting Logan's eloquence as a speaker, when in fact Logan never publicly delivered the speech. Instead, Logan sent a message that contained his speech to Lord Dunmore, and Logan never attended the treaty meeting himself.[8] Cresap's involvement in the massacre had been denied as well, and Jefferson was accused of perpetuating an assumption of guilt against Cresap. Further, other critics had pointed to evidence the none of Logan’s children had died in the massacres of 1774, and that the Indians murdered were not, in fact, Logan’s immediate family.[9]

Regardless of its origin, Logan's speech had a lasting effect on American culture. Still relevant well into the nineteenth century, the speech was praised for having "mingled pride, courage, and sorrow" and subsequently "elevated the character of the native American throughout the intelligent world."[10] Theodore Roosevelt even wrote that the speech was "perhaps the finest outburst of savage eloquence of which we have any authentic record."[11]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

See also

- A Manual of Parliamentary Practice for the Use of the Senate of the United States

- Notes on the State of Virginia

- Thomas Jefferson

- Wythe's Library

References

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (London: John Stockdale, Opposite Burlington-House, Piccadilly, 1787), 104-05.

- ↑ Jefferson, Notes, 105-06.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, An Appendix to the Notes on Virginia Relative to the Murder of Logan's Family (Philadelphia: S.H. Smith, 1800), 4.

- ↑ Ibid., 3.

- ↑ Ibid., 4.

- ↑ Thomas Warren Field, An Essay Towards an Indian Bibliography: Being a Catalogue of Books, Relating to the History, Antiquities, Languages, Customs, Religion, Wars, Literature, and Origin of the American Indians, in the Library of Thomas W. Field; with Bibliographical and Historical Notes, and Synopses of the Contents of Some of the Works Least Known (New York: Scribner, Armstrong, and Co., 1873), 190.

- ↑ "American Review," The Monthly Magazine and American Review 3, no. 1 (July 1800): 51.

- ↑ Edward D. Seeber, "Critical Views on Logan's Speech," The Journal of American Folklore 60, no. 236 (1947): 137.

- ↑ Ibid., 134.

- ↑ Charles Whittlesey, Fugitive Essays, Upon Interesting and Useful Subjects, Relating to the Early History of Ohio: Its Geology and Agriculture, with a Biography of the First Successful Constructor of Steamboats; A Dissertation upon the Antiquity of the Material Universe, and Other Articles, Being a Reprint from Various Periodicals of the Day (Hudson, OH: Sawyer, Ingersoll and Co., 1852), 145.

- ↑ Theodore Roosevelt, The Winning of the West, vol. 1, From the Alleghanies to the Mississippi (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1889), 237.