Difference between revisions of "Burnsides v. Reid"

(→Background) |

m (→Wythe's Discussion) |

||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE:''Burnsides v. Reid''}} | {{DISPLAYTITLE:''Burnsides v. Reid''}} | ||

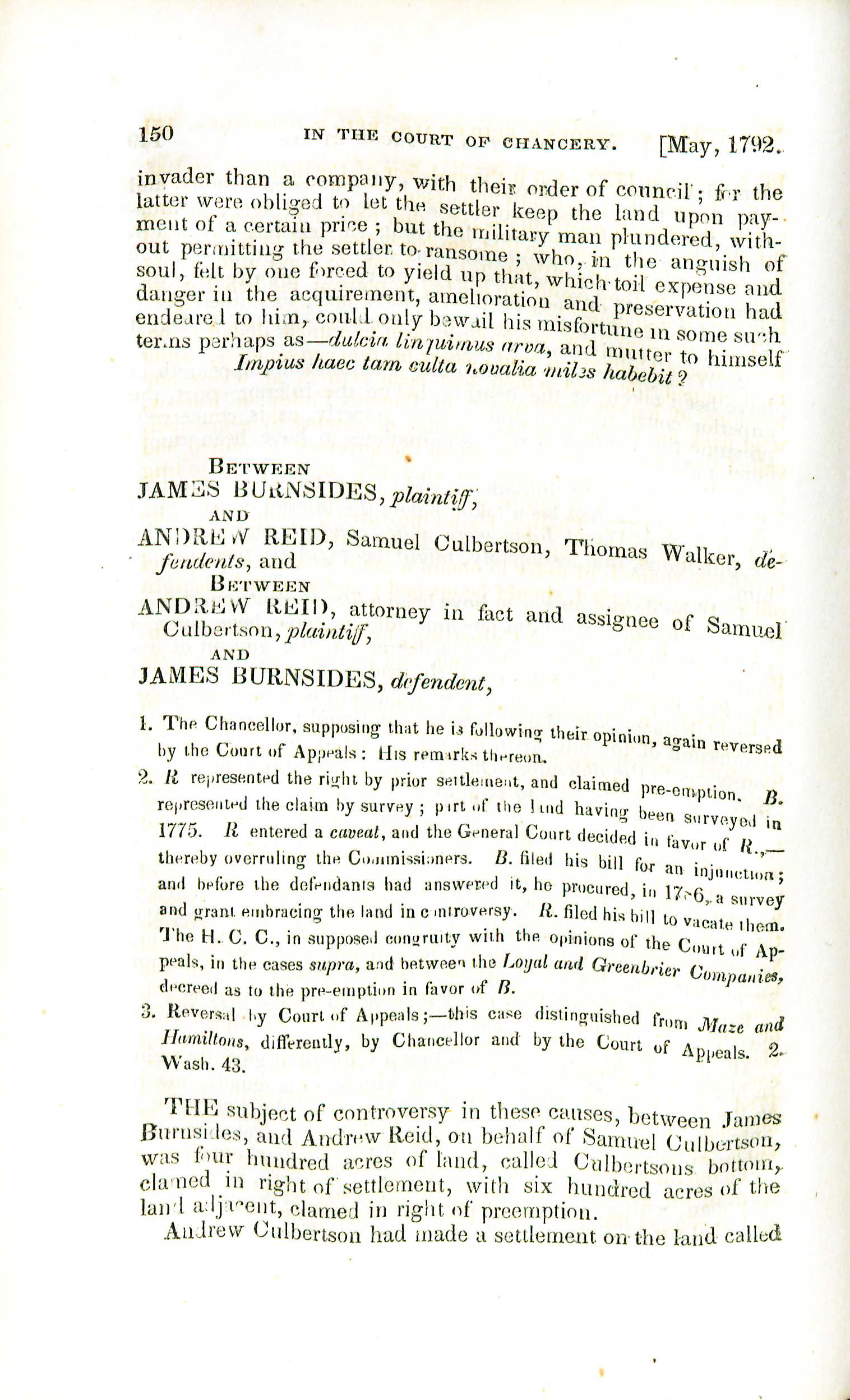

| − | [[File:WytheBurnsidesVReid1852.jpg|thumb|right|300px|First page of the opinion ''Burnsides v. Reid'', in [https:// | + | [[File:WytheBurnsidesVReid1852.jpg|link={{filepath:WytheDecisions1852BurnsidesVReid.pdf}}|thumb|right|300px|First page of the opinion [[Media:WytheDecisions1852BurnsidesVReid.pdf|''Burnsides v. Reid'']], in [https://wm.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/g9pr7p/alma991006014269703196 ''Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery, with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions''], by George Wythe. 2nd ed. (Richmond: J. W. Randolph, 1852).]] |

| − | ''Burnsides v. Reid'', Wythe 150 (1792),<ref>George Wythe, ''[[Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery]],'' | + | ''Burnsides v. Reid'', [[Media:WytheDecisions1852BurnsidesVReid.pdf|Wythe 150 (1792)]],<ref>George Wythe, ''[[Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery (1852)|Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions]],'' 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852): 150.</ref> rev'd, [[Media:WashBurnsidesvReid1799v2p43.pdf|2 Va. (2 Wash.) 43 (1794)]],<ref>Bushrod Washington, ''[[Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Court of Appeals of Virginia]],'' (Richmond: T. Nicolson, 1798), 2:43.</ref> involved a dispute over who owned a parcel of land. It is also a prime example of Wythe venting his frustration with the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia through his case reporting. |

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| − | In 1748, the Virginia Council granted 800,000 acres of land in western Virginia to the land company [[ | + | In 1748, the Virginia Council granted 800,000 acres of land in western Virginia to the land company [[wikipedia:Loyal Company of Virginia|Loyal Company of Virginia]]. |

| − | In 1753, Andrew Culbertson claimed a 400-acre parcel by right of settlement called Culbertson's Bottom, now known as Crump's Bottom in Summers County, West Virginia. Andrew also claimed 600 acres adjacent to Culbertson's Bottom by right of pre-emption.<ref>Right of pre-emption allows someone to claim land under some circumstances (such as claiming land adjacent to the main claim) as long as no one else has claimed it first.</ref> The [[ | + | In 1753, Andrew Culbertson claimed a 400-acre parcel by right of settlement called Culbertson's Bottom, now known as Crump's Bottom in Summers County, West Virginia. Andrew also claimed 600 acres adjacent to Culbertson's Bottom by right of pre-emption.<ref>Right of pre-emption allows someone to claim land under some circumstances (such as claiming land adjacent to the main claim) as long as no one else has claimed it first.</ref> The [[wikipedia:French and Indian War|French and Indian War]] broke out soon after Andrew settled the area, and American Indian forces repeatedly raided Culbertson's Bottom and other areas nearby. As a result, Andrew sold Culbertson's Bottom to Samuel Culbertson in 1753 or 1754. In 1755 Samuel also abandoned the settlement for several years. Wythe stated that the Culbertsons seemed to have taken every step reasonably possible to show that they had not intended to completely abandon their claim to the settlement, but Culbertson's Bottom still appeared to be deserted to an everyday observer. |

In 1775, Thomas Farley bought 355 acres of land in Culbertson's Bottom from Loyal Company, and surveyed it so that he would have the necessary paperwork to receive a grant for the land when the land office re-opened.<ref>Wythe's report only notes that the land office was closed at the time, but presumably the buildup to the American Revolution caused the land office to suspend operations for several years.</ref> Farley assigned his rights to James Burnsides. | In 1775, Thomas Farley bought 355 acres of land in Culbertson's Bottom from Loyal Company, and surveyed it so that he would have the necessary paperwork to receive a grant for the land when the land office re-opened.<ref>Wythe's report only notes that the land office was closed at the time, but presumably the buildup to the American Revolution caused the land office to suspend operations for several years.</ref> Farley assigned his rights to James Burnsides. | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

Burnsides then applied to (presumably, although Wythe does not say it) the High Court of Chancery for an injunction against enforcing the General Court's order. Burnsides also asked the Chancery Court to force Loyal Company agent Thomas Walker to consent to granting Burnsides's land claim. Burnsides argued that: | Burnsides then applied to (presumably, although Wythe does not say it) the High Court of Chancery for an injunction against enforcing the General Court's order. Burnsides also asked the Chancery Court to force Loyal Company agent Thomas Walker to consent to granting Burnsides's land claim. Burnsides argued that: | ||

| + | |||

*Because Virginia did not recognize the right to land by settlement until 1779 and did not make that right retroactive, Culbertson's rights to the land by settlement were invalid; | *Because Virginia did not recognize the right to land by settlement until 1779 and did not make that right retroactive, Culbertson's rights to the land by settlement were invalid; | ||

*An order the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals issued on May 2, 1783, confirmed all surveys that were done by a county surveyor or the surveyor's deputies and commissioned by the Loyal Company and another land company, the Greenbrier Company<ref>[[Maze v. Hamilton]], Wythe 51, 52-53 (1791).</ref>. This order legitimized Burnsides's claim to the land. | *An order the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals issued on May 2, 1783, confirmed all surveys that were done by a county surveyor or the surveyor's deputies and commissioned by the Loyal Company and another land company, the Greenbrier Company<ref>[[Maze v. Hamilton]], Wythe 51, 52-53 (1791).</ref>. This order legitimized Burnsides's claim to the land. | ||

*Andrew transferred his rights to the land to someone else, and Burnsides bought the rights from that person.<ref>Wythe did not lend any credence to Burnsides's evidence supporting this argument, and discussed it no further.</ref> | *Andrew transferred his rights to the land to someone else, and Burnsides bought the rights from that person.<ref>Wythe did not lend any credence to Burnsides's evidence supporting this argument, and discussed it no further.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

The Chancery Court issued an injunction against enforcing the General Court's decision in May 1785 until further order. | The Chancery Court issued an injunction against enforcing the General Court's decision in May 1785 until further order. | ||

| Line 28: | Line 30: | ||

Wythe says he would like to issue a ruling similar to the one he did in [[Maze v. Hamilton]], but notes that the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals reversed that. Wythe begins a run-on sentence/paragraph for the ages by stating that someone who read the Virginia statute passed in 1779 that created the settler's right of pre-emption would think that a settler would have rights to both the settled land and the land he had right of pre-emption to against a land company that surveyed the area, including the land after the settler had established his homestead. In a bout of frustration, Wythe said that judging from [[Maze v. Hamilton]], the Virginia Supreme Court obviously felt otherwise, and that it has decided to give land companies the right to the pre-emptive land, even if the land company didn't survey its claim until years after the settler made his claim. | Wythe says he would like to issue a ruling similar to the one he did in [[Maze v. Hamilton]], but notes that the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals reversed that. Wythe begins a run-on sentence/paragraph for the ages by stating that someone who read the Virginia statute passed in 1779 that created the settler's right of pre-emption would think that a settler would have rights to both the settled land and the land he had right of pre-emption to against a land company that surveyed the area, including the land after the settler had established his homestead. In a bout of frustration, Wythe said that judging from [[Maze v. Hamilton]], the Virginia Supreme Court obviously felt otherwise, and that it has decided to give land companies the right to the pre-emptive land, even if the land company didn't survey its claim until years after the settler made his claim. | ||

| − | + | [[File:WashingtonBurnsidesvReid1799v2p43.jpg|link=Media:WashBurnsidesvReid1799v2p43.pdf|thumb|left|300px|First page of the opinion [[Media:WashBurnsidesvReid1799v2p43.pdf|''Burnsides v. Reid'']], in [http://wm-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/01COWM_WM:EVERYTHING:01COWM_WM_ALMA21560662660003196 ''Reports of Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Court of Appeals of Virginia''], by Bushrod Washington. Richmond: T. Nicolson, 1798.]] | |

The reader can practically hear Wythe's exasperated sigh as he says that to stay in line with the Supreme Court's jurisprudence, the Chancery Court ordered a survey to be made of the 400 acres comprising Culbertson's Bottom, then to survey Burnsides's land patent to see how much overlap between the two claims there were. The Chancery Court ordered Burnsides to then turn over to Reid whatever land in Burnsides's claim overlapped with Samuel's claim. In exchange, Reid was to pay Burnsides £3 for every 100 acres Burnsides had to give up. The Chancery Court dismissed Reid's claim for the 600 adjacent acres, but said that Reid was welcome to survey 600 adjacent acres in right of pre-emption if he could find land that was not in Burnsides's patent or claimed by anyone else. | The reader can practically hear Wythe's exasperated sigh as he says that to stay in line with the Supreme Court's jurisprudence, the Chancery Court ordered a survey to be made of the 400 acres comprising Culbertson's Bottom, then to survey Burnsides's land patent to see how much overlap between the two claims there were. The Chancery Court ordered Burnsides to then turn over to Reid whatever land in Burnsides's claim overlapped with Samuel's claim. In exchange, Reid was to pay Burnsides £3 for every 100 acres Burnsides had to give up. The Chancery Court dismissed Reid's claim for the 600 adjacent acres, but said that Reid was welcome to survey 600 adjacent acres in right of pre-emption if he could find land that was not in Burnsides's patent or claimed by anyone else. | ||

| Line 34: | Line 36: | ||

The Supreme Court noted that in the current case Burnsides did not survey his claim until 1786, after Culbertson had established his claim to the land, and after the General Court had found in favor of Reid. Therefore, the Supreme Court said that Burnsides's patent for the land "was founded upon a rotten foundation",<ref>2 Va. 43, 48.</ref> and Burnsides's claim of priority over the Culbertsons' and Reid's rights failed. The Supreme Court ordered a survey taken of Samuel's settlement claim of 400 acres and 600 adjoining acres, then a survey taken of Burnsides's claim. The Court also ordered Burnsides to turn over to Reid any part of Burnsides's claimed land that overlapped with Andrew's claim, with Reid reimbursing Burnsides £3 per hundred acres. The Supreme Court ordered Burnsides to pay Chancery Court costs for both sides. | The Supreme Court noted that in the current case Burnsides did not survey his claim until 1786, after Culbertson had established his claim to the land, and after the General Court had found in favor of Reid. Therefore, the Supreme Court said that Burnsides's patent for the land "was founded upon a rotten foundation",<ref>2 Va. 43, 48.</ref> and Burnsides's claim of priority over the Culbertsons' and Reid's rights failed. The Supreme Court ordered a survey taken of Samuel's settlement claim of 400 acres and 600 adjoining acres, then a survey taken of Burnsides's claim. The Court also ordered Burnsides to turn over to Reid any part of Burnsides's claimed land that overlapped with Andrew's claim, with Reid reimbursing Burnsides £3 per hundred acres. The Supreme Court ordered Burnsides to pay Chancery Court costs for both sides. | ||

| + | |||

==Wythe's Discussion== | ==Wythe's Discussion== | ||

| − | Wythe | + | B.B. Minor, editor of the [[Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery (1852)|1852 Reports]], makes clear Wythe's frustration with the Virginia Court of Appeals from the very first headnote to the case: "1. The Chancellor, supposing that he is following their opinion, again reversed by the Court of Appeals".<ref>Wythe 150.</ref> Wythe noted that the Supreme Court's decision claims to reverse the Chancery Court, but repeated the Chancery Court's directive in awarding Reid the 400 acres of Culbertson's Bottom — an act, Wythe said, that the Supreme Court repeated almost verbatim in [[Ross v. Pleasants]]. |

Wythe said that when he originally handed down his decision it was an error and against his better judgment, but he thought the result was what the Supreme Court wanted. As it turned out, "he was mistaken". Wythe added that it is hard to avoid such mistakes, and a look at the Supreme Court's decision would illustrate why.<ref>Wythe adds that the case of [[Hill v. Gregory]] was another case where the Supreme Court's arguments did not logically lead to its conclusion. Wythe 150, 156, fn. f.</ref> | Wythe said that when he originally handed down his decision it was an error and against his better judgment, but he thought the result was what the Supreme Court wanted. As it turned out, "he was mistaken". Wythe added that it is hard to avoid such mistakes, and a look at the Supreme Court's decision would illustrate why.<ref>Wythe adds that the case of [[Hill v. Gregory]] was another case where the Supreme Court's arguments did not logically lead to its conclusion. Wythe 150, 156, fn. f.</ref> | ||

| Line 41: | Line 44: | ||

Wythe said that in [[Maze v. Hamilton]], Hamilton's right to the adjacent land came solely from a survey authorized by the Greenbrier Company. Despite what the Virginia Supreme Court said, Wythe stated that Burnsides's rights to the land in the current case also came from a survey. The Loyal Company sold the land rights to Farley in 1775 - the same year that Farley surveyed the land and sold his rights to Burnsides. Burnsides's 1786 survey may have been too late to give Burnsides any rights, but under the Supreme Court's logic in [[Maze v. Hamilton]], Wythe says, Farley's interest should pre-empt Samuel Culbertson's interest in the land adjacent to Culbertson's Bottom. | Wythe said that in [[Maze v. Hamilton]], Hamilton's right to the adjacent land came solely from a survey authorized by the Greenbrier Company. Despite what the Virginia Supreme Court said, Wythe stated that Burnsides's rights to the land in the current case also came from a survey. The Loyal Company sold the land rights to Farley in 1775 - the same year that Farley surveyed the land and sold his rights to Burnsides. Burnsides's 1786 survey may have been too late to give Burnsides any rights, but under the Supreme Court's logic in [[Maze v. Hamilton]], Wythe says, Farley's interest should pre-empt Samuel Culbertson's interest in the land adjacent to Culbertson's Bottom. | ||

| − | Wythe continued by stating that one of the differences between [[Maze v. Hamilton]] and the current case was that Hamilton did not have the rights to his land through the Greenbrier Company's survey until after the General Court had certified Maze's claim in the land.<ref>Wythe does not say this explicitly, but presumably his thinking is that it was the subsequent Supreme Court decree in [[Maze v. Hamilton]] that validated the Greenbrier Company's survey.</ref> In the current case, on the other hand, Burnsides's claim by way of Farley's purchase from the Loyal Company already had the land rights by survey that the Supreme Court's decree in [[Maze v. Hamilton]] created. | + | Wythe continued by stating that one of the differences between [[Maze v. Hamilton]] and the current case was that Hamilton did not have the rights to his land through the Greenbrier Company's survey until after the General Court had certified Maze's claim in the land.<ref> Wythe does not say this explicitly, but presumably his thinking is that it was the subsequent Supreme Court decree in [[Maze v. Hamilton]] that validated the Greenbrier Company's survey.</ref> In the current case, on the other hand, Burnsides's claim by way of Farley's purchase from the Loyal Company already had the land rights by survey that the Supreme Court's decree in [[Maze v. Hamilton]] created. |

Furthermore, Wythe argued, the Virginia Supreme Court in [[Williams v. Jacob]] said that any sort of survey, even one issued under the authority of a military warrant<ref>A grant of land awarded for military service</ref>, gives superior land rights to the person who commissioned the survey, even over settlers currently in possession of the land. It makes no sense, Wythe says, that under this precedent the Culbertsons' right in settlement should be superior to Burnsides's; unlike Burnsides, the Culbertsons never got any land rights from the Loyal Company. | Furthermore, Wythe argued, the Virginia Supreme Court in [[Williams v. Jacob]] said that any sort of survey, even one issued under the authority of a military warrant<ref>A grant of land awarded for military service</ref>, gives superior land rights to the person who commissioned the survey, even over settlers currently in possession of the land. It makes no sense, Wythe says, that under this precedent the Culbertsons' right in settlement should be superior to Burnsides's; unlike Burnsides, the Culbertsons never got any land rights from the Loyal Company. | ||

Wythe finished by saying he would have approved the General Court's decree because the General Court's ruling was unappealable under Virginia statutes.<ref>Wythe did not specify which part of the Virginia statutes does this; he might be referring to Chapter 17 of the October 1777 session, "An Act for Establishing a General Court", 9 Hening 401 (1777).</ref> If the Virginia Supreme Court should nevertheless decide that they should hear an appeal, Wythe continued, they may want to ask themselves whether a verdict against Burnsides, an innocent purchaser who knew nothing of Samuel's title to Culbertson's Bottom, would be consistent with its precedent. | Wythe finished by saying he would have approved the General Court's decree because the General Court's ruling was unappealable under Virginia statutes.<ref>Wythe did not specify which part of the Virginia statutes does this; he might be referring to Chapter 17 of the October 1777 session, "An Act for Establishing a General Court", 9 Hening 401 (1777).</ref> If the Virginia Supreme Court should nevertheless decide that they should hear an appeal, Wythe continued, they may want to ask themselves whether a verdict against Burnsides, an innocent purchaser who knew nothing of Samuel's title to Culbertson's Bottom, would be consistent with its precedent. | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | ==References== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

[[Category:Cases]] | [[Category:Cases]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Real Property]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:55, 15 May 2024

Burnsides v. Reid, Wythe 150 (1792),[1] rev'd, 2 Va. (2 Wash.) 43 (1794),[2] involved a dispute over who owned a parcel of land. It is also a prime example of Wythe venting his frustration with the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia through his case reporting.

Background

In 1748, the Virginia Council granted 800,000 acres of land in western Virginia to the land company Loyal Company of Virginia.

In 1753, Andrew Culbertson claimed a 400-acre parcel by right of settlement called Culbertson's Bottom, now known as Crump's Bottom in Summers County, West Virginia. Andrew also claimed 600 acres adjacent to Culbertson's Bottom by right of pre-emption.[3] The French and Indian War broke out soon after Andrew settled the area, and American Indian forces repeatedly raided Culbertson's Bottom and other areas nearby. As a result, Andrew sold Culbertson's Bottom to Samuel Culbertson in 1753 or 1754. In 1755 Samuel also abandoned the settlement for several years. Wythe stated that the Culbertsons seemed to have taken every step reasonably possible to show that they had not intended to completely abandon their claim to the settlement, but Culbertson's Bottom still appeared to be deserted to an everyday observer.

In 1775, Thomas Farley bought 355 acres of land in Culbertson's Bottom from Loyal Company, and surveyed it so that he would have the necessary paperwork to receive a grant for the land when the land office re-opened.[4] Farley assigned his rights to James Burnsides.

Samuel had moved a great distance away from Culbertson's Bottom, so he was unable to assert his title to the land before Farley purchased it. In May 1779, Samuel empowered Andrew Reid to recover possession of the land.

In 1782, Burnsides asked the Virginia Court of Commissioners[5] to award him a grant for the land. Reid filed a caveat with the court asking them not to award the land to Burnsides. The court of commissioners granted Burnsides the rights to 400 acres, including the 355 Farley had surveyed, along with the rights to 600 adjacent acres by pre-emption.

Reid filed a petition with the General Court of Virginia asking it to reverse the Court of Commissioners' award. Reid's petition said that "unavoidable accidents" had prevented Reid from presenting evidence to the commissioners that would have proven his claim, and asked the General Court to hear the evidence. The General Court allowed Reid's evidence, and it reversed the Court of Commissioners' decision on October 12, 1784. The General Court awarded a grant to Samuel for the 400 acres of Culbertson's Bottom by settlement, and the 600 adjacent acres by right of pre-emption.

Burnsides then applied to (presumably, although Wythe does not say it) the High Court of Chancery for an injunction against enforcing the General Court's order. Burnsides also asked the Chancery Court to force Loyal Company agent Thomas Walker to consent to granting Burnsides's land claim. Burnsides argued that:

- Because Virginia did not recognize the right to land by settlement until 1779 and did not make that right retroactive, Culbertson's rights to the land by settlement were invalid;

- An order the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals issued on May 2, 1783, confirmed all surveys that were done by a county surveyor or the surveyor's deputies and commissioned by the Loyal Company and another land company, the Greenbrier Company[6]. This order legitimized Burnsides's claim to the land.

- Andrew transferred his rights to the land to someone else, and Burnsides bought the rights from that person.[7]

The Chancery Court issued an injunction against enforcing the General Court's decision in May 1785 until further order.

In January 1786, before the Chancery Court could issue a final ruling on the case, Burnsides made a survey of 1200 acres that included Culbertson's Bottom and got a patent (an official validation of a claim) for the land. Reid then filed suit in the Chancery Court against Burnsides to repeal this patent; Reid's suit (Reid v. Burnsides) was combined with Burnsides's (Burnsides v. Reid) in the Chancery Court's decision.

The Court's Decision

On May 15, 1792, the High Court of Chancery issued its opinion. Wythe begins by stating that Burnsides was guilty of fraud when he applied for and obtained the land patent while the Chancery Court was still hearing the case. Had the land office known of the General Court decision, Wythe says, they would not have granted the land to Burnsides. Wythe adds that the decree mentioned in Maze v. Hamilton that validated the Greenbrier and Loyal Companies' surveys did not validate Burnsides's survey because Burnsides's claim was not based on a survey by either of those companies, but on a survey Burnsides commissioned personally.

Wythe says he would like to issue a ruling similar to the one he did in Maze v. Hamilton, but notes that the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals reversed that. Wythe begins a run-on sentence/paragraph for the ages by stating that someone who read the Virginia statute passed in 1779 that created the settler's right of pre-emption would think that a settler would have rights to both the settled land and the land he had right of pre-emption to against a land company that surveyed the area, including the land after the settler had established his homestead. In a bout of frustration, Wythe said that judging from Maze v. Hamilton, the Virginia Supreme Court obviously felt otherwise, and that it has decided to give land companies the right to the pre-emptive land, even if the land company didn't survey its claim until years after the settler made his claim.

The reader can practically hear Wythe's exasperated sigh as he says that to stay in line with the Supreme Court's jurisprudence, the Chancery Court ordered a survey to be made of the 400 acres comprising Culbertson's Bottom, then to survey Burnsides's land patent to see how much overlap between the two claims there were. The Chancery Court ordered Burnsides to then turn over to Reid whatever land in Burnsides's claim overlapped with Samuel's claim. In exchange, Reid was to pay Burnsides £3 for every 100 acres Burnsides had to give up. The Chancery Court dismissed Reid's claim for the 600 adjacent acres, but said that Reid was welcome to survey 600 adjacent acres in right of pre-emption if he could find land that was not in Burnsides's patent or claimed by anyone else.

On October 1, 1794, the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals reversed the High Court of Chancery's decision.[8] The Supreme Court said that the current case was different from Maze v. Hamilton. In Maze v. Hamilton, Hamilton surveyed his claim in 1775 under the Greenbrier Company's authority, before the case had entered the courts, and before the 1779 Virginia statute retroactively awarding land rights by settlement. Maze founded his 400-acre settlement in 1764, giving Maze the priority of right to those 400 acres. Maze's claimed right of pre-emption to the adjacent 1100 acres, however, was only valid against unclaimed land. Since Hamilton had properly claimed that adjacent land under the 1779 statute, Maze did not have the right to it.

The Supreme Court noted that in the current case Burnsides did not survey his claim until 1786, after Culbertson had established his claim to the land, and after the General Court had found in favor of Reid. Therefore, the Supreme Court said that Burnsides's patent for the land "was founded upon a rotten foundation",[9] and Burnsides's claim of priority over the Culbertsons' and Reid's rights failed. The Supreme Court ordered a survey taken of Samuel's settlement claim of 400 acres and 600 adjoining acres, then a survey taken of Burnsides's claim. The Court also ordered Burnsides to turn over to Reid any part of Burnsides's claimed land that overlapped with Andrew's claim, with Reid reimbursing Burnsides £3 per hundred acres. The Supreme Court ordered Burnsides to pay Chancery Court costs for both sides.

Wythe's Discussion

B.B. Minor, editor of the 1852 Reports, makes clear Wythe's frustration with the Virginia Court of Appeals from the very first headnote to the case: "1. The Chancellor, supposing that he is following their opinion, again reversed by the Court of Appeals".[10] Wythe noted that the Supreme Court's decision claims to reverse the Chancery Court, but repeated the Chancery Court's directive in awarding Reid the 400 acres of Culbertson's Bottom — an act, Wythe said, that the Supreme Court repeated almost verbatim in Ross v. Pleasants.

Wythe said that when he originally handed down his decision it was an error and against his better judgment, but he thought the result was what the Supreme Court wanted. As it turned out, "he was mistaken". Wythe added that it is hard to avoid such mistakes, and a look at the Supreme Court's decision would illustrate why.[11]

Wythe said that in Maze v. Hamilton, Hamilton's right to the adjacent land came solely from a survey authorized by the Greenbrier Company. Despite what the Virginia Supreme Court said, Wythe stated that Burnsides's rights to the land in the current case also came from a survey. The Loyal Company sold the land rights to Farley in 1775 - the same year that Farley surveyed the land and sold his rights to Burnsides. Burnsides's 1786 survey may have been too late to give Burnsides any rights, but under the Supreme Court's logic in Maze v. Hamilton, Wythe says, Farley's interest should pre-empt Samuel Culbertson's interest in the land adjacent to Culbertson's Bottom.

Wythe continued by stating that one of the differences between Maze v. Hamilton and the current case was that Hamilton did not have the rights to his land through the Greenbrier Company's survey until after the General Court had certified Maze's claim in the land.[12] In the current case, on the other hand, Burnsides's claim by way of Farley's purchase from the Loyal Company already had the land rights by survey that the Supreme Court's decree in Maze v. Hamilton created.

Furthermore, Wythe argued, the Virginia Supreme Court in Williams v. Jacob said that any sort of survey, even one issued under the authority of a military warrant[13], gives superior land rights to the person who commissioned the survey, even over settlers currently in possession of the land. It makes no sense, Wythe says, that under this precedent the Culbertsons' right in settlement should be superior to Burnsides's; unlike Burnsides, the Culbertsons never got any land rights from the Loyal Company.

Wythe finished by saying he would have approved the General Court's decree because the General Court's ruling was unappealable under Virginia statutes.[14] If the Virginia Supreme Court should nevertheless decide that they should hear an appeal, Wythe continued, they may want to ask themselves whether a verdict against Burnsides, an innocent purchaser who knew nothing of Samuel's title to Culbertson's Bottom, would be consistent with its precedent.

References

- ↑ George Wythe, Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852): 150.

- ↑ Bushrod Washington, Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Court of Appeals of Virginia, (Richmond: T. Nicolson, 1798), 2:43.

- ↑ Right of pre-emption allows someone to claim land under some circumstances (such as claiming land adjacent to the main claim) as long as no one else has claimed it first.

- ↑ Wythe's report only notes that the land office was closed at the time, but presumably the buildup to the American Revolution caused the land office to suspend operations for several years.

- ↑ This was a court created by a 1779 Virginia Act of Assembly to decide disputes between settlers. Wythe 150, 151.

- ↑ Maze v. Hamilton, Wythe 51, 52-53 (1791).

- ↑ Wythe did not lend any credence to Burnsides's evidence supporting this argument, and discussed it no further.

- ↑ Burnsides v. Reid, 2 Va. (2 Wash.) 43 (1794).

- ↑ 2 Va. 43, 48.

- ↑ Wythe 150.

- ↑ Wythe adds that the case of Hill v. Gregory was another case where the Supreme Court's arguments did not logically lead to its conclusion. Wythe 150, 156, fn. f.

- ↑ Wythe does not say this explicitly, but presumably his thinking is that it was the subsequent Supreme Court decree in Maze v. Hamilton that validated the Greenbrier Company's survey.

- ↑ A grant of land awarded for military service

- ↑ Wythe did not specify which part of the Virginia statutes does this; he might be referring to Chapter 17 of the October 1777 session, "An Act for Establishing a General Court", 9 Hening 401 (1777).