Difference between revisions of "Harrison v. Allen"

(→Background) |

m |

||

| (13 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE:''Harrison v. Allen''}} | {{DISPLAYTITLE:''Harrison v. Allen''}} | ||

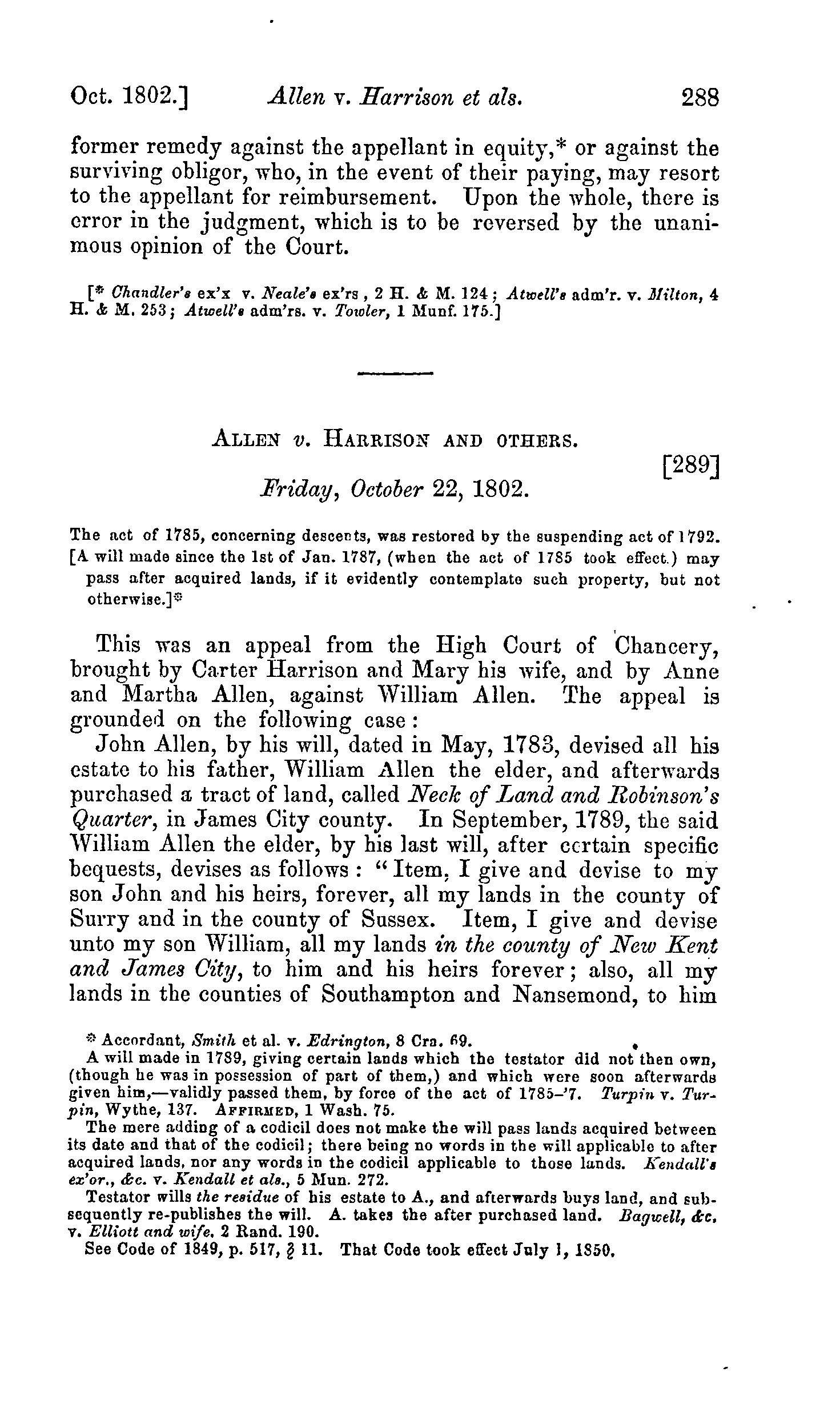

| − | ''Harrison v. Allen'', Wythe 291 (1794),<ref>George Wythe, ''[[Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery]],'' (Richmond: | + | [[File:WytheHarrisonVAllen1852.jpg|link={{filepath:WytheDecisions1852HarrisonVAllen.pdf}}|thumb|right|300px|First page of the opinion [[Media:WytheDecisions1852HarrisonVAllen.pdf|''Harrison v. Allen'']], in [https://wm.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/g9pr7p/alma991006014269703196 ''Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery, with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions''], by George Wythe. 2nd ed. (Richmond: J. W. Randolph, 1852).]] |

| + | [[Media:WytheDecisions1852HarrisonVAllen.pdf|''Harrison v. Allen'']], Wythe 291 (1794),<ref>George Wythe, ''[[Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery (1852)|Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions]],'' 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852), 291.</ref> ''aff'd'', [[Media:CallsReports1854V3AllenvHarrison.pdf|''Allen v. Harrison'']], 7 Va. 288, 3 Call 289 (1802),<ref>Daniel Call, ''Reports of Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Court of Appeals of Virginia, '' 3rd ed., ed. Lucian Minor (Richmond: A. Morris, | ||

| + | 1854), 251.</ref> was a dispute over an estate that has an early example of statutory interpretation by a Virginia court. | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| − | The Virginia Assembly passed a statute that took force in January 1787, | + | The Virginia Assembly passed a statute that took force in January 1787, allowing people to pass down property using testaments, and stated that without a testament, a person's property would go to all their children, and then to all the children's descendants. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | On December 8, 1792, the Virginia Assembly passed a statute that consolidated various earlier statutes on inheriting property into one. The new statute included the exact language from the 1787 statute. The 1792 statute also said that any previous acts falling under its purview were repealed. On December 28, 1792, the Assembly passed an act that suspended the December 8 statute from taking effect until October 1, 1793. | ||

| + | [[File:CallAllenVHarrison1854v3p288.jpg|link=Media:CallsReports1854V3AllenvHarrison.pdf|thumb|left|300px|First page of the opinion [[Media:CallsReports1854V3AllenvHarrison.pdf|''Allen v. Harrison'']], in ''Reports of Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Court of Appeals of Virginia'', by Daniel Call. 3rd ed. Richmond: A. Morris, 1854.]] | ||

In November 1789, the Assembly had passed a law stating that if a law repeals an older law, and that law is itself repealed, the older law does not take effect again unless the Assembly expressly says it does. | In November 1789, the Assembly had passed a law stating that if a law repeals an older law, and that law is itself repealed, the older law does not take effect again unless the Assembly expressly says it does. | ||

| − | William Allen (Sr.) wrote a testament in September 1789 that divided his property among his children, including William Allen (Jr.) and Mary Howell (married to the plaintiff, Carter Bassett Harrison). William Sr. did not change or repeal this testament before dying in July 1793, roughly three months before the December 8, 1792 | + | William Allen (Sr.) wrote a testament in September 1789 that divided his property among his children, including William Allen (Jr.) and Mary Howell (married to the plaintiff, Carter Bassett Harrison). William Sr. did not change or repeal this testament before dying in July 1793, roughly three months before the December 8, 1792 law was to take effect. |

William Jr. argued that because the December 28 act did not expressly return the 1787 law to effect when it suspended the the December 8 law, the common law would be in effect. Because the common law did not allow daughters to inherit, William Jr. said, all of William Sr.'s estate should go to him. | William Jr. argued that because the December 28 act did not expressly return the 1787 law to effect when it suspended the the December 8 law, the common law would be in effect. Because the common law did not allow daughters to inherit, William Jr. said, all of William Sr.'s estate should go to him. | ||

==The Court's Decision== | ==The Court's Decision== | ||

| − | The High Court of Chancery stated that the important thing to consider was the assembly's will in passing the statutes. | + | The High Court of Chancery stated that the important thing to consider was the assembly's will in passing the statutes. Because the December 8 law contained the same language as the 1787 statute, the assembly's will was not to repeal the 1787 act. In addition, the December 28 law only suspended, instead of repealed, the December 8 law. Therefore, the High Court of Chancery concluded that the provision allowing people to give property by testament and allowing all children to inherit was still in effect, and issued a decree in favor of Harrison. |

| + | |||

| + | The Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia affirmed the High Court of Chancery's decree.<ref>''Allen v. Harrison'', 7 Va. 288, 3 Call 289 (1802).</ref> | ||

| − | + | ==References== | |

| − | |||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

[[Category:Cases]] | [[Category:Cases]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Inheritance]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Procedure]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:20, 29 March 2022

Harrison v. Allen, Wythe 291 (1794),[1] aff'd, Allen v. Harrison, 7 Va. 288, 3 Call 289 (1802),[2] was a dispute over an estate that has an early example of statutory interpretation by a Virginia court.

Background

The Virginia Assembly passed a statute that took force in January 1787, allowing people to pass down property using testaments, and stated that without a testament, a person's property would go to all their children, and then to all the children's descendants.

On December 8, 1792, the Virginia Assembly passed a statute that consolidated various earlier statutes on inheriting property into one. The new statute included the exact language from the 1787 statute. The 1792 statute also said that any previous acts falling under its purview were repealed. On December 28, 1792, the Assembly passed an act that suspended the December 8 statute from taking effect until October 1, 1793.

In November 1789, the Assembly had passed a law stating that if a law repeals an older law, and that law is itself repealed, the older law does not take effect again unless the Assembly expressly says it does.

William Allen (Sr.) wrote a testament in September 1789 that divided his property among his children, including William Allen (Jr.) and Mary Howell (married to the plaintiff, Carter Bassett Harrison). William Sr. did not change or repeal this testament before dying in July 1793, roughly three months before the December 8, 1792 law was to take effect.

William Jr. argued that because the December 28 act did not expressly return the 1787 law to effect when it suspended the the December 8 law, the common law would be in effect. Because the common law did not allow daughters to inherit, William Jr. said, all of William Sr.'s estate should go to him.

The Court's Decision

The High Court of Chancery stated that the important thing to consider was the assembly's will in passing the statutes. Because the December 8 law contained the same language as the 1787 statute, the assembly's will was not to repeal the 1787 act. In addition, the December 28 law only suspended, instead of repealed, the December 8 law. Therefore, the High Court of Chancery concluded that the provision allowing people to give property by testament and allowing all children to inherit was still in effect, and issued a decree in favor of Harrison.

The Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia affirmed the High Court of Chancery's decree.[3]

References

- ↑ George Wythe, Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852), 291.

- ↑ Daniel Call, Reports of Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Court of Appeals of Virginia, 3rd ed., ed. Lucian Minor (Richmond: A. Morris, 1854), 251.

- ↑ Allen v. Harrison, 7 Va. 288, 3 Call 289 (1802).