Difference between revisions of "Rights of Man"

m |

m |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{DISPLAYTITLE:''Rights of Man''}} | + | {{DISPLAYTITLE:''Rights of Man: Being an Answer to Mr. Burke's Attack on the French Revolution''}} |

===by Thomas Paine=== | ===by Thomas Paine=== | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

|desc=[[:Category:Octavos|8vo (22 cm.)]] | |desc=[[:Category:Octavos|8vo (22 cm.)]] | ||

|shelf=E-1 | |shelf=E-1 | ||

| − | }}Revolutionary, author, pamphleteer, [ | + | }}Revolutionary, author, pamphleteer, [[wikipedia:Thomas Paine|Thomas Paine]] (1737–1809) had the ability to communicate the ideas of the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Age_of_revolution Age of Revolution] in plain English. He is considered one of the most radical thinkers of the age.<ref>Erick Foner, "[http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-01251.html Paine, Thomas]" in ''American National Biography Online'', accessed October 3, 2013.</ref> Paine was born in Thetford, Norfolk, England.<ref>Ibid.</ref> He spent his youth in England and met with limited success in his various enterprises. At thirty-seven, on the recommendation of [[wikipedia:Benjamin Franklin|Benjamin Franklin]], Paine moved to America.<ref>Foner, "Paine, Thomas."</ref> He began working as a journalist, and used his skill in writing and debate to support and promote the [[wikipedia:American Revolution|American Revolution]]. His pamphlet ''[[wikipedia:Common Sense|Common Sense]]'' "became one of the most successful and influential pamphlets in the history of political writing."<ref>Ibid.</ref> It helped the colonists see independence as "both desirable and attainable."<ref>Mark Philip, "[http://www.oxforddnb.com.proxy.wm.edu/view/article/21133 Paine, Thomas (1737–1809)]" in ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', accessed October 3, 2013.</ref> |

| − | + | ||

| − | After the American Revolution, Paine returned to England, where he became acquainted with [ | + | After the American Revolution, Paine returned to England, where he became acquainted with [[wikipedia:Edmund Burke|Edmund Burke]].<ref>Ibid.</ref> When Burke attacked the [[wikipedia:French Revolution|French Revolution]] in ''[[wikipedia:Reflections on the Revolution in France|Reflections on the Revolution in France]]'', Paine responded with ''The Rights of Man''.<ref>Ibid.</ref> He defended the French Revolution, repudiating monarchies and the concept of "hereditary" governments.<ref>Philip, "Paine Thomas."</ref>Because of his arguments against monarchy, Paine was charged with seditious libel, causing him to flee England for France never to return. During his time in France, Paine was imprisoned for speaking out against executing [[wikipedia:King Louis XVI|King Louis XVI]].<ref>Ibid.</ref> While in prison, Paine wrote ''The Age of Reason''. He was released from prison with the help of [[wikipedia:James Monroe|James Monroe]] and returned to America.<ref>Ibid.</ref> He found that because of his criticisms of the Church in ''The Age of Reason'', he was no longer popular in the United States. When Paine died on June 8, 1809 only a handful of people attended his funeral.<ref>Philip, "Paine Thomas."</ref> |

[[File:PaineRightsOfMan1791Inscription.jpg|left|thumb|300px|<center>Inscription, front pastedown.</center>]] | [[File:PaineRightsOfMan1791Inscription.jpg|left|thumb|300px|<center>Inscription, front pastedown.</center>]] | ||

| + | |||

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

In a [[Wythe to Thomas Jefferson, 15 June 1792|letter]] to [[Thomas Jefferson]] from June 1792, George Wythe wrote, "I thank you for the 'rights of man' which you sent to me."<ref>[http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mtj.mtjbib006303 George Wythe to Thomas Jefferson, June 15, 1792], in ''The Thomas Jefferson Papers, Series 1 General Correspondence 1651-1827'' (Washington DC: Library of Congress, 1974), images 715-18.</ref> Both the Brown Bibliography<ref>Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433.</ref> and [http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe George Wythe's Library]<ref>''LibraryThing'', s.v. "[http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe Member: George Wythe]," accessed on March 19, 2014.</ref> on LibraryThing include the first edition (1791) of Thomas Paine's ''Rights of Man: Being an Answer to Mr. Burke's Attack on the French Revolution''. Brown also lists the second edition (1792) of the sequel ''Rights of Man: Part the Second, Combining Principle and Practice''. Both parts of ''Rights of Man'' went through multiple editions within months of their initial publications and we do not have enough information to verify which edition(s) Wythe owned. The Wolf Law Library purchased a copy of the eighth editions of part one (1791) and part two (1792) bound together. | In a [[Wythe to Thomas Jefferson, 15 June 1792|letter]] to [[Thomas Jefferson]] from June 1792, George Wythe wrote, "I thank you for the 'rights of man' which you sent to me."<ref>[http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mtj.mtjbib006303 George Wythe to Thomas Jefferson, June 15, 1792], in ''The Thomas Jefferson Papers, Series 1 General Correspondence 1651-1827'' (Washington DC: Library of Congress, 1974), images 715-18.</ref> Both the Brown Bibliography<ref>Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433.</ref> and [http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe George Wythe's Library]<ref>''LibraryThing'', s.v. "[http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe Member: George Wythe]," accessed on March 19, 2014.</ref> on LibraryThing include the first edition (1791) of Thomas Paine's ''Rights of Man: Being an Answer to Mr. Burke's Attack on the French Revolution''. Brown also lists the second edition (1792) of the sequel ''Rights of Man: Part the Second, Combining Principle and Practice''. Both parts of ''Rights of Man'' went through multiple editions within months of their initial publications and we do not have enough information to verify which edition(s) Wythe owned. The Wolf Law Library purchased a copy of the eighth editions of part one (1791) and part two (1792) bound together. | ||

Latest revision as of 15:43, 8 January 2025

by Thomas Paine

| Rights of Man | |

|

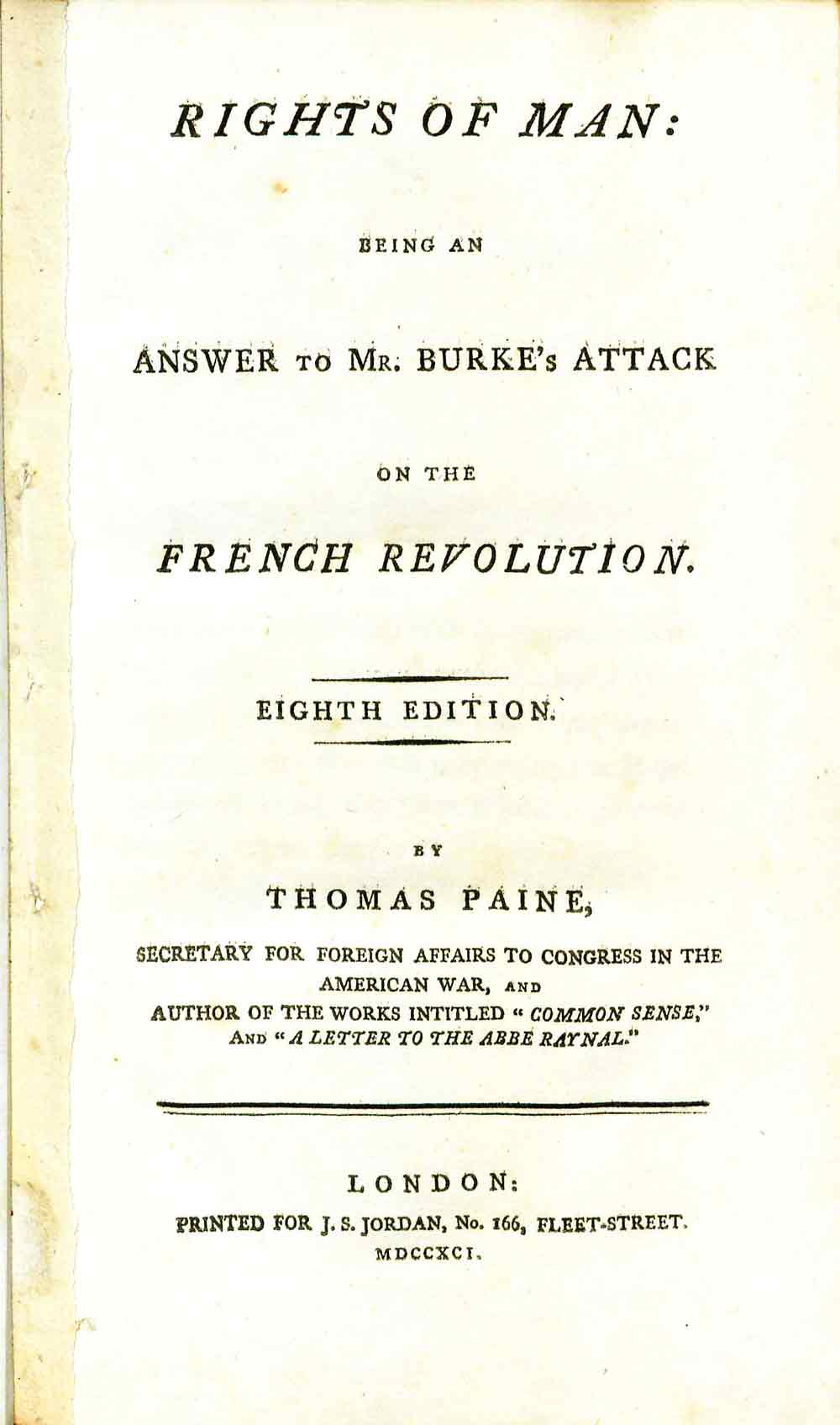

Title page from Rights of Man, part one, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Thomas Paine |

| Published | London: Printed for J.S. Jordan |

| Date | 1791-1792 |

| Edition | Eighth |

| Language | English |

| Volumes | 2 parts in 1 volume set |

| Pages | x, 171 (part one); xv, 178 (part two). |

| Desc. | 8vo (22 cm.) |

| Location | Shelf E-1 |

Revolutionary, author, pamphleteer, Thomas Paine (1737–1809) had the ability to communicate the ideas of the Age of Revolution in plain English. He is considered one of the most radical thinkers of the age.[1] Paine was born in Thetford, Norfolk, England.[2] He spent his youth in England and met with limited success in his various enterprises. At thirty-seven, on the recommendation of Benjamin Franklin, Paine moved to America.[3] He began working as a journalist, and used his skill in writing and debate to support and promote the American Revolution. His pamphlet Common Sense "became one of the most successful and influential pamphlets in the history of political writing."[4] It helped the colonists see independence as "both desirable and attainable."[5]

After the American Revolution, Paine returned to England, where he became acquainted with Edmund Burke.[6] When Burke attacked the French Revolution in Reflections on the Revolution in France, Paine responded with The Rights of Man.[7] He defended the French Revolution, repudiating monarchies and the concept of "hereditary" governments.[8]Because of his arguments against monarchy, Paine was charged with seditious libel, causing him to flee England for France never to return. During his time in France, Paine was imprisoned for speaking out against executing King Louis XVI.[9] While in prison, Paine wrote The Age of Reason. He was released from prison with the help of James Monroe and returned to America.[10] He found that because of his criticisms of the Church in The Age of Reason, he was no longer popular in the United States. When Paine died on June 8, 1809 only a handful of people attended his funeral.[11]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

In a letter to Thomas Jefferson from June 1792, George Wythe wrote, "I thank you for the 'rights of man' which you sent to me."[12] Both the Brown Bibliography[13] and George Wythe's Library[14] on LibraryThing include the first edition (1791) of Thomas Paine's Rights of Man: Being an Answer to Mr. Burke's Attack on the French Revolution. Brown also lists the second edition (1792) of the sequel Rights of Man: Part the Second, Combining Principle and Practice. Both parts of Rights of Man went through multiple editions within months of their initial publications and we do not have enough information to verify which edition(s) Wythe owned. The Wolf Law Library purchased a copy of the eighth editions of part one (1791) and part two (1792) bound together.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in early nineteenth century full tan diced calf. Spine with raised bands, tooled ornaments, brown title label, and gilt lettering. Front pastedown includes the inscription "Charles Austin, Chapel View, Robin Hood" written over a previous inscription. Purchased from Paul Foster.

Images of the library's copy of this book are available on Flickr. View the record for this book in part one and part two of William & Mary's online catalog.

See also

References

- ↑ Erick Foner, "Paine, Thomas" in American National Biography Online, accessed October 3, 2013.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Foner, "Paine, Thomas."

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Mark Philip, "Paine, Thomas (1737–1809)" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, accessed October 3, 2013.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Philip, "Paine Thomas."

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Philip, "Paine Thomas."

- ↑ George Wythe to Thomas Jefferson, June 15, 1792, in The Thomas Jefferson Papers, Series 1 General Correspondence 1651-1827 (Washington DC: Library of Congress, 1974), images 715-18.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433.

- ↑ LibraryThing, s.v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on March 19, 2014.