Difference between revisions of "Demosthenis et Aeschinis Opera"

m (→by Demosthenes and Aeschines) |

m (→by Demosthenes and Aeschines) |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

Also a statesman and orator, [[wikipedia:Aeschines|Aeschines]] (389 – 314 BCE) was a bitter political opponent of Demosthenes. He was raised in humble circumstances and worked as an actor before becoming a member of the embassies to Philip II. He eventually provoked Philip II to establish Macedonian control over central Greece. Unlike Demosthenes, Aeschines was more conciliatory to the Macedonians as they expanded. The two orators collided when Aeschines brought suit against a certain [[wikipedia:Ctesiphon (orator)|Ctesiphon]], for proposing the award of a crown to Demosthenes in recognition of his services to Athens. Aeschines suffered a resounding defeat in the trial and subsequently left Athens for [[wikipedia:Rhodes|Rhodes]] where he taught rhetoric.<ref>Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, s.v. "[http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/7407/Aeschines Aeschines]," accessed November 14, 2013.</ref> | Also a statesman and orator, [[wikipedia:Aeschines|Aeschines]] (389 – 314 BCE) was a bitter political opponent of Demosthenes. He was raised in humble circumstances and worked as an actor before becoming a member of the embassies to Philip II. He eventually provoked Philip II to establish Macedonian control over central Greece. Unlike Demosthenes, Aeschines was more conciliatory to the Macedonians as they expanded. The two orators collided when Aeschines brought suit against a certain [[wikipedia:Ctesiphon (orator)|Ctesiphon]], for proposing the award of a crown to Demosthenes in recognition of his services to Athens. Aeschines suffered a resounding defeat in the trial and subsequently left Athens for [[wikipedia:Rhodes|Rhodes]] where he taught rhetoric.<ref>Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, s.v. "[http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/7407/Aeschines Aeschines]," accessed November 14, 2013.</ref> | ||

| − | In 1572, the German historian and classical scholar, [[wikipedia:Hieronymus Wolf|Hieronymus Wolf]] (1516 – 1580), published a volume of Demosthenes' and Aeschines' speeches, in parallel Greek and Latin text, with commentary and ancient and modern notes.<ref>Hieronymus Wolf, ed., ''Demosthenis Et Aeschinis Principum Græciæ Oratorum Opera'' (Basel: Ex officina Heruagiana, per Evsebivm Episcopium, 1572).</ref> Along with his own notes, Wolf included classical commentary by [[wikipedia:Ulpian|Ulpian]] (c. 170 – 223 or 228), as well as notes on the uses of Greek by the French scholar [[wikipedia:Guillaume Budé|Guillaume Budé]] (1467 – 1540), first published in 1529.<ref>Guillaume Budé, ''Commentarii Linguae Graecae'' (Paris: Venundantur Iodoco Badio Ascensio, 1529). A "complete" edition of Budé's ''Commentarii'' was published posthumously, in 1548.</ref> Wolf's edition was reprinted in 1604, 1607, and 1642, and remained the most important text of Demosthenes until the 19th century.<ref>Charles Darwin Adams, [https://books.google.com/books?id=_sgyAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA134 ''Demosthenes and His Influence,''] vol. 5 (New York: Longmans, Green, 1927) 134-135, 145-146.</ref> | + | In 1572, the German historian and classical scholar, [[wikipedia:Hieronymus Wolf|Hieronymus Wolf]] (1516 – 1580), published a volume of Demosthenes' and Aeschines' speeches, in parallel Greek and Latin text, with commentary and ancient and modern notes.<ref>Hieronymus Wolf, ed., ''Demosthenis Et Aeschinis Principum Græciæ Oratorum Opera'' (Basel: Ex officina Heruagiana, per Evsebivm Episcopium, 1572).</ref> Along with his own notes, Wolf included classical commentary by [[wikipedia:Ulpian|Ulpian]] (c. 170 – 223 or 228), as well as notes on the uses of Greek by the French scholar [[wikipedia:Guillaume Budé|Guillaume Budé]] (1467 – 1540), first published in 1529.<ref>Guillaume Budé, ''Commentarii Linguae Graecae'' (Paris: Venundantur Iodoco Badio Ascensio, 1529). A "complete" edition of Budé's ''Commentarii'' was published posthumously, in 1548.</ref> Wolf's edition was reprinted in 1604, 1607, and 1642, and remained the most important text of Demosthenes until the 19th century.<ref>Charles Darwin Adams, [https://books.google.com/books?id=_sgyAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA134 ''Demosthenes and His Influence,''] vol. 5 (New York: Longmans, Green, 1927), 134-135, 145-146.</ref> |

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

Revision as of 08:33, 14 September 2024

by Demosthenes and Aeschines

| Demosthenis et Aeschinis Opera | ||

|

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | Demosthenes, Aeschines | |

| Editor | Hieronymus Wolf | |

| Edition | Precise edition unknown | |

| Language | Greek, Latin | |

| Desc. | Folio | |

Demosthenes (384 – 322 BCE) was a prominent statesman and orator in Ancient Greece. He developed his skills as an orator by studying speeches given by earlier great orators.[1] He transferred his talents as an orator and writer into a successful professional speech-writing career. During his time as an orator, Demosthenes developed an interest in politics; he went on to devote most of his career to opposing Macedonia's expansion. He spoke out against both Philip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great. Demosthenes played a leading role in his city's uprising against Alexander. The revolt was met with harsh reprisals and Demosthenes committed suicide to prevent being arrested. Demosthenes' oratory works were highly influential during the Middle Ages and Renaissance,[2] and inspired the authors of the Federalist Papers and the major orators of the French Revolution.[3]

Also a statesman and orator, Aeschines (389 – 314 BCE) was a bitter political opponent of Demosthenes. He was raised in humble circumstances and worked as an actor before becoming a member of the embassies to Philip II. He eventually provoked Philip II to establish Macedonian control over central Greece. Unlike Demosthenes, Aeschines was more conciliatory to the Macedonians as they expanded. The two orators collided when Aeschines brought suit against a certain Ctesiphon, for proposing the award of a crown to Demosthenes in recognition of his services to Athens. Aeschines suffered a resounding defeat in the trial and subsequently left Athens for Rhodes where he taught rhetoric.[4]

In 1572, the German historian and classical scholar, Hieronymus Wolf (1516 – 1580), published a volume of Demosthenes' and Aeschines' speeches, in parallel Greek and Latin text, with commentary and ancient and modern notes.[5] Along with his own notes, Wolf included classical commentary by Ulpian (c. 170 – 223 or 228), as well as notes on the uses of Greek by the French scholar Guillaume Budé (1467 – 1540), first published in 1529.[6] Wolf's edition was reprinted in 1604, 1607, and 1642, and remained the most important text of Demosthenes until the 19th century.[7]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

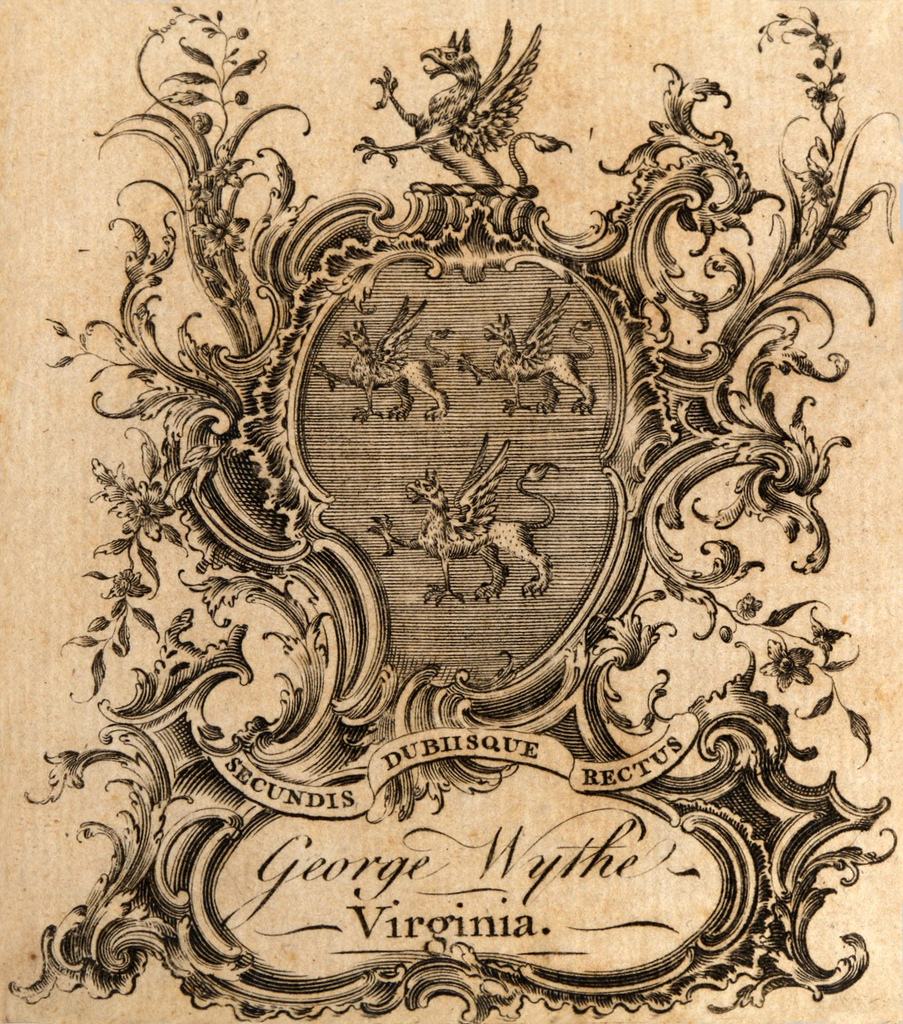

In 1795, an arthritic Wythe directed a young Henry Clay to add some references to Greek classics in the end pages of a special few of his newly published reports, Decisions of Cases in Virginia, by the High Court of Chancery — presentation copies intended for Wythe's former students, friends, and peers at court.[8] In 1851, Clay reflected upon this task before the publication of a new edition of the reports:

Upon [Chancellor Wythe's] dictation, I wrote, I believe, all the reports of cases which it is now proposed to re-publish. I remember that it cost me a great deal of labor, not understanding a single Greek character, to write some citations from Greek authors, which he wished inserted in copies of his reports sent to Mr. Jefferson, Mr. Samuel Adams, of Boston, and to one or two other persons.[9] I copied them by imitating each character as I found them in the original works.[10]

The cited authors in this added "Appendix" included Aeschylus, Demosthenes, Herodotus, Homer, Sophocles, and Thucydides. Hieronymus Wolf's collection of Demosthenes and Aeschines contains everything required for creating Wythe's selections from the speeches of Demosthenes, "Against Meidias," and "Against Aphobus": it contains these specific speeches; the text is in both in both Greek and Latin; and following Wythe's selected section from "Aphobus" is written: 'On this passage is the following note:', accompanied by Guillaume Budé's commentary on the word διαιτητάς ("arbitration"), included at the end of Wolf's edition.[11] While other titles containing selected works by Demosthenes were owned by Wythe, they either did not include the cited speeches, or were not printed in both Greek and Latin. None of the books in his library are known to include notes by Budé, and no other editions available to Wythe meet all three requirements.

While it is probable Wythe used a copy of Wolf's Demosthenis et Aeschines to make his "Appendix," the precise edition is unknown. Wolf's 1604 edition is a likely candidate. George Wythe's compatriot from Massachusetts, John Adams, had a copy of the 1604 edition in his home library.[12]

See also

- Decisions of Cases in Virginia, by the High Court of Chancery

- Dēmosthenous Logoi Eklektoi

- Henry Clay to B. B. Minor, 3 May 1851

- Life and Public Services of Henry Clay

- Œuvres Complettes de Démosthene et d'Eschine

- Wythe's Library

- Wythe to John Adams, 5 December 1783

- Wythe to Samuel Adams, 1 August 1778

References

- ↑ Ian Worthington, Demosthenes: Statesman and Orator (London: Routledge, 2000), 240.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, s.v. "Demosthenes," accessed October 24, 2013.

- ↑ Konstantinos Tsatsos, "XV" in Demosthenes (Athens: Estia, 1975), 352.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, s.v. "Aeschines," accessed November 14, 2013.

- ↑ Hieronymus Wolf, ed., Demosthenis Et Aeschinis Principum Græciæ Oratorum Opera (Basel: Ex officina Heruagiana, per Evsebivm Episcopium, 1572).

- ↑ Guillaume Budé, Commentarii Linguae Graecae (Paris: Venundantur Iodoco Badio Ascensio, 1529). A "complete" edition of Budé's Commentarii was published posthumously, in 1548.

- ↑ Charles Darwin Adams, Demosthenes and His Influence, vol. 5 (New York: Longmans, Green, 1927), 134-135, 145-146.

- ↑ There are four of these added appendices know to be extant: two at the University of Virginia, in Jefferson's copy of Wythe's Reports, and in Wythe's personal copy; one at the New York Historical Society in a copy sent to Chancellor Robert Livingston; and as a loose manuscript at the Newberry Library, separated from an unidentified copy of the Reports, but with provenance leading back to Boston.

- ↑ Although Wythe corresponded at least once with Samuel Adams (enclosing a poem), another candidate could be John Adams, with whom Wythe once shared a quote from Homer's Odyssey in Greek.

- ↑ William Maxwell, ed., "Letter from Hon. Henry Clay to B.B. Minor, Esq.," Virginia Historical Register, and Literary Companion 5, no. 3 (July 1852), 162-167. Reprinted in B.B. Minor, ed., "Memoir of the Author," Decisions of Cases in Virginia, by the High Court Chancery, with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, by George Wythe, (Richmond, VA: J.W. Randolph, 1852), xxxii-xxxvi.

- ↑ Hieronymus Wolf, ed., Demosthenis Et Aeschinis Principum Græciæ Oratorum Opera (Frankfurt: Apud Claudium Marnium, & Hæredes Iohannis Aubbrii, 1604), 1224.

- ↑ "Catalogue of the John Adams library in the Public Library of the City of Boston" (Boston: Boston Public Library, 1917), 72, listed as: 'Demosthenis et Æschinis ... opera, cum vtriusque autoris vita & Vlpiani commentariis, nouisque scholiis, ex quarta ... recognitione, Græcolatina: ... annotationibvs illustrata: per Hieronymvm Wolfivm Œtingensem ... Accedit vita Demosthenis ex parallelis Andresæ Schotti ... Francofvrti. M.DC.IIII.'

External links

- Read this book in Google Books.