Difference between revisions of "Hill v. Gregory"

m (→Works Cited or Referenced by Wythe) |

|||

| (20 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE:''Hill v. Gregory''}} | {{DISPLAYTITLE:''Hill v. Gregory''}} | ||

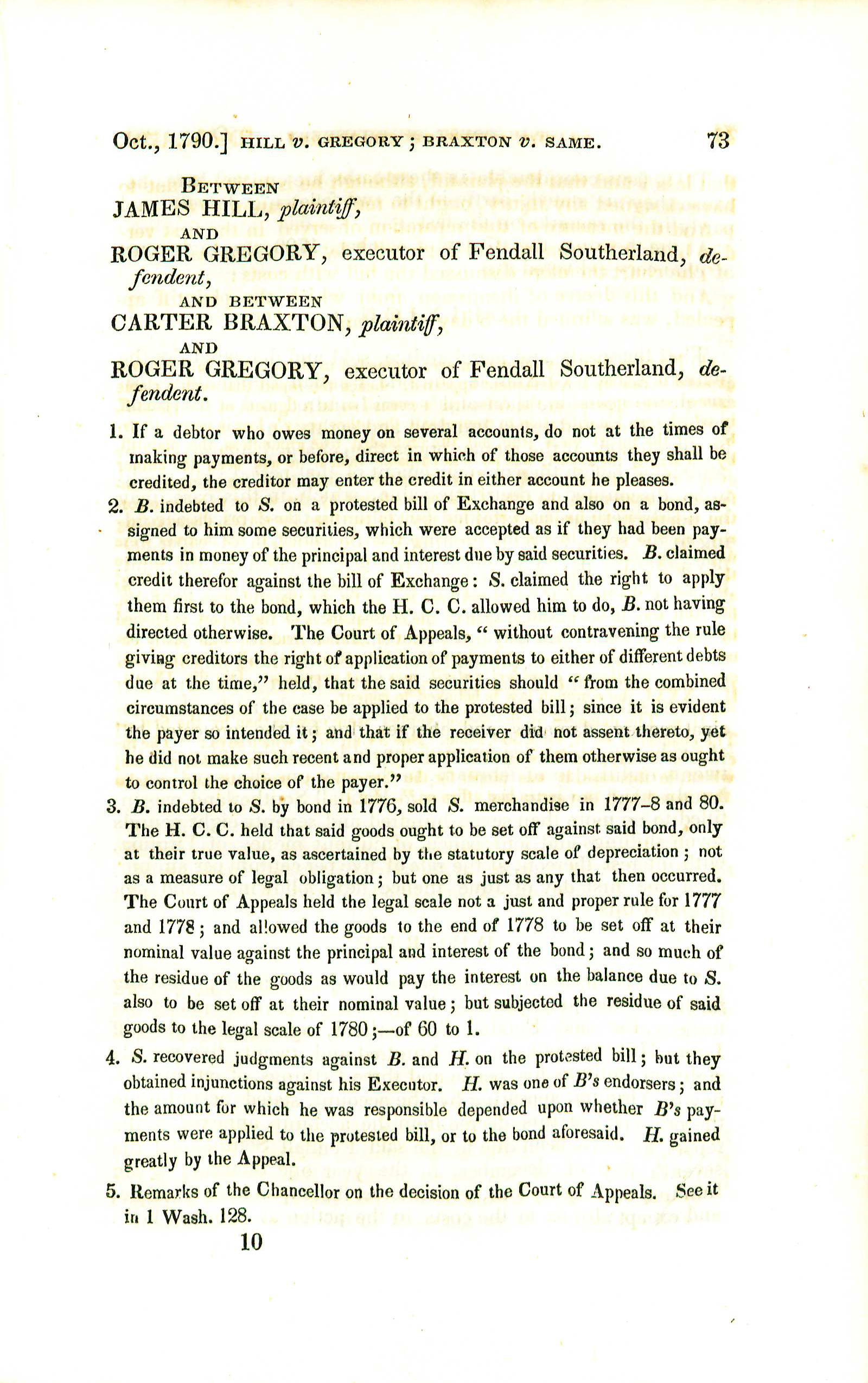

| − | ''Hill v. Gregory'', Wythe 73 (1790), was a case that discussed whether a creditor could choose how to apply a payment among a debtor's different accounts in the absence of specific directions from the debtor.<ref>George Wythe, ''Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery,'' (Richmond: | + | [[File:WytheHillVGregory1852.jpg|link={{filepath:WytheDecisions1852HillVGregory.pdf}}|thumb|right|300px|First page of the opinion [[Media:WytheDecisions1852HillVGregory.pdf|''Hill v. Gregory'']], in [https://wm.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/g9pr7p/alma991006014269703196 ''Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery, with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions''], by George Wythe. 2nd ed. (Richmond: J. W. Randolph, 1852).]] |

| + | [[Media:WytheDecisions1852HillVGregory.pdf|''Hill v. Gregory'']], Wythe 73 (1790), was a case that discussed whether a creditor could choose how to apply a payment among a debtor's different accounts in the absence of specific directions from the debtor.<ref>George Wythe, ''[[Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery (1852)|Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions]],'' 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852), 73. The subsequent Court of Appeals decision is ''Hill & Braxton v. Southerland's Executors'', 1 Va. (1 Wash.) 128 (1792).</ref> | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

| − | |||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| − | Fendall Southerland held a bill of exchange and a bond issued by Carter Braxton (the listed defendant, Roger Gregory, was executor of Southerland's estate). James Hill endorsed the bill of exchange, and so was also liable to Southerland for any amount of that bill that Braxton could not cover. Braxton assigned some securities to Southerland and claimed that their value would be credited to the bill of exchange, but Southerland credited them to the bond instead. Braxton had issued the bond in 1776, and had sold Southerland merchandise between 1777 and 1780. Southerland held Braxton's bill until 1784, and then Southerland filed suit and won a judgment for £361. Braxton was able to get this judgment reversed, and then in 1787, Southerland sued Hill and won a judgment for £1400. Hill sued and got an injunction from the High Court of Chancery, stating that Braxton had already paid off most of the bill, at which point the | + | Fendall Southerland held a bill of exchange and a bond issued by Carter Braxton (the listed defendant, Roger Gregory, was executor of Southerland's estate). James Hill endorsed the bill of exchange, and so was also liable to Southerland for any amount of that bill that Braxton could not cover. Braxton assigned some securities to Southerland and claimed that their value would be credited to the bill of exchange, but Southerland credited them to the bond instead. Braxton had issued the bond in 1776, and had sold Southerland merchandise between 1777 and 1780. Southerland held Braxton's bill until 1784, and then Southerland filed suit and won a judgment for £361. Braxton was able to get this judgment reversed, and then in 1787, Southerland sued Hill and won a judgment for £1400. Hill sued and got an injunction from the High Court of Chancery (HCC), stating that Braxton had already paid off most of the bill, at which point the HCC added Braxton as a co-plaintiff. |

==The Court's Decision== | ==The Court's Decision== | ||

| − | The High Court of Chancery allowed Southerland to credit Braxton's securities to the bond, stating that Braxton had not specified otherwise, and determined that the goods Braxton sold Southerland should be credited against the bond at their actual value as determined by the legal scale of depreciation. The Court of Appeals reversed, stating that it was evident that Braxton intended the payment to go towards the bill of exchange, and that | + | The High Court of Chancery allowed Southerland to credit Braxton's securities to the bond, stating that Braxton had not specified otherwise, and determined that the goods Braxton sold Southerland should be credited against the bond at their actual value as determined by the legal scale of depreciation. The Court of Appeals reversed, stating that it was evident that Braxton intended the payment to go towards the bill of exchange, and therefore, that Gregory should credit the accounts that way. Furthermore, the Court of Appeals said that the merchandise Braxton sold Southerland during 1777 and 1778 had extra value at the time, due to the dangers of smuggling imports during the American Revolution, and that the goods sold during those years should be credited against the bond at the theoretical value they would have had back then. The rest of the goods, the Court of Appeals said, should be credited at their actual value, determined by the legal scale of 60 to 1 for goods from 1780. |

==Wythe's Discussion== | ==Wythe's Discussion== | ||

| − | Wythe | + | Wythe began by noting that it wasn't really necessary for the Court of Appeals to take a paragraph to affirm that the case had been properly brought before the High Court of Chancery, opining that this was well-settled law for nearly two centuries. Wythe then proceeded to describe Braxton's and Southerland's situation as a logical syllogism: the major proposition is the general legal principle that if a debtor does not specify which of several accounts a payment should be applied to, the creditor is free to apply that payment to whichever account the creditor chooses. The minor proposition is that when Braxton provided payment to Southerland, Braxton did not specify that the payment should go towards the bill of exchange. Therefore, Southerland was entitled to apply Braxton's payment to the bond. This syllogism, Wythe said, was the basis for the HCC's decree. If the HCC's decision is in error, Wythe stated, there must be a problem with either the major or minor proposition. The Court of Appeals seems to agree with the major proposition, Wythe continued, so unless the minor proposition was erroneous, the HCC's decision was proper. |

| + | |||

| + | The minor proposition — whether Braxton specified which account should get credited with the payment — was an issue of fact, and for this discussion, Wythe took the facts as the Court of Appeals interpreted them. Wythe noted that the Court of Appeals said that Braxton "intended" for the payment to go towards the bill of exchange, but Wythe commented that intention is not notification or direction. The Court of Appeals also faulted Southerland for not having made a "recent and proper" application of the payment; Wythe countered that once the money was in Southerland's hands, absent any instructions on how to apply it from Braxton, there was no principle of law that required Southerland to apply the payment in a "recent and proper" manner — the money was Southerland's to do with as he pleased. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Wythe found the Court of Appeals' decision on the value of the goods Braxton sold Southerland contradictory. Either the legal scale for depreciating goods is legitimate or it is not, Wythe said. The Court of Appeals, however, said that the scale is good for some years, such as 1780, but not for other years, such as 1777 and 1778. And if the Court of Appeals adjusts the value of Braxton's goods to help offset depreciation, Wythe continued, why doesn't it extend the same courtesy to the debt owed Southerland? According to Wythe, the Court of Appeals says there is precedent for their decision, but he had doubts on that point. Wythe concluded by stating that in the future the High Court of Chancery will probably leave questions of valuation up to juries. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Works Cited or Referenced by Wythe== | ||

| + | ===Francis Bacon's, ''[[Of the Advancement and Proficiencie of Learning|Of the Advancement and Proficiencie of Learning: or, the Partitions of Sciences, Nine Books. ...]]''=== | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | <tt> | ||

| + | <span style="color: #006600;">In syllogismo fit reductio propositionum ad principia per propositiones medias. Haec autem sive inveniendi sive probandi forma in scientiis popularibus (veluti ethicis, politicis, legibus, et hujusmodi) locum habet.</span> | ||

| + | </tt> | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 18: | Line 30: | ||

[[Category:Cases]] | [[Category:Cases]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Debtor-Creditor]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:25, 3 April 2023

Hill v. Gregory, Wythe 73 (1790), was a case that discussed whether a creditor could choose how to apply a payment among a debtor's different accounts in the absence of specific directions from the debtor.[1]

Background

Fendall Southerland held a bill of exchange and a bond issued by Carter Braxton (the listed defendant, Roger Gregory, was executor of Southerland's estate). James Hill endorsed the bill of exchange, and so was also liable to Southerland for any amount of that bill that Braxton could not cover. Braxton assigned some securities to Southerland and claimed that their value would be credited to the bill of exchange, but Southerland credited them to the bond instead. Braxton had issued the bond in 1776, and had sold Southerland merchandise between 1777 and 1780. Southerland held Braxton's bill until 1784, and then Southerland filed suit and won a judgment for £361. Braxton was able to get this judgment reversed, and then in 1787, Southerland sued Hill and won a judgment for £1400. Hill sued and got an injunction from the High Court of Chancery (HCC), stating that Braxton had already paid off most of the bill, at which point the HCC added Braxton as a co-plaintiff.

The Court's Decision

The High Court of Chancery allowed Southerland to credit Braxton's securities to the bond, stating that Braxton had not specified otherwise, and determined that the goods Braxton sold Southerland should be credited against the bond at their actual value as determined by the legal scale of depreciation. The Court of Appeals reversed, stating that it was evident that Braxton intended the payment to go towards the bill of exchange, and therefore, that Gregory should credit the accounts that way. Furthermore, the Court of Appeals said that the merchandise Braxton sold Southerland during 1777 and 1778 had extra value at the time, due to the dangers of smuggling imports during the American Revolution, and that the goods sold during those years should be credited against the bond at the theoretical value they would have had back then. The rest of the goods, the Court of Appeals said, should be credited at their actual value, determined by the legal scale of 60 to 1 for goods from 1780.

Wythe's Discussion

Wythe began by noting that it wasn't really necessary for the Court of Appeals to take a paragraph to affirm that the case had been properly brought before the High Court of Chancery, opining that this was well-settled law for nearly two centuries. Wythe then proceeded to describe Braxton's and Southerland's situation as a logical syllogism: the major proposition is the general legal principle that if a debtor does not specify which of several accounts a payment should be applied to, the creditor is free to apply that payment to whichever account the creditor chooses. The minor proposition is that when Braxton provided payment to Southerland, Braxton did not specify that the payment should go towards the bill of exchange. Therefore, Southerland was entitled to apply Braxton's payment to the bond. This syllogism, Wythe said, was the basis for the HCC's decree. If the HCC's decision is in error, Wythe stated, there must be a problem with either the major or minor proposition. The Court of Appeals seems to agree with the major proposition, Wythe continued, so unless the minor proposition was erroneous, the HCC's decision was proper.

The minor proposition — whether Braxton specified which account should get credited with the payment — was an issue of fact, and for this discussion, Wythe took the facts as the Court of Appeals interpreted them. Wythe noted that the Court of Appeals said that Braxton "intended" for the payment to go towards the bill of exchange, but Wythe commented that intention is not notification or direction. The Court of Appeals also faulted Southerland for not having made a "recent and proper" application of the payment; Wythe countered that once the money was in Southerland's hands, absent any instructions on how to apply it from Braxton, there was no principle of law that required Southerland to apply the payment in a "recent and proper" manner — the money was Southerland's to do with as he pleased.

Wythe found the Court of Appeals' decision on the value of the goods Braxton sold Southerland contradictory. Either the legal scale for depreciating goods is legitimate or it is not, Wythe said. The Court of Appeals, however, said that the scale is good for some years, such as 1780, but not for other years, such as 1777 and 1778. And if the Court of Appeals adjusts the value of Braxton's goods to help offset depreciation, Wythe continued, why doesn't it extend the same courtesy to the debt owed Southerland? According to Wythe, the Court of Appeals says there is precedent for their decision, but he had doubts on that point. Wythe concluded by stating that in the future the High Court of Chancery will probably leave questions of valuation up to juries.

Works Cited or Referenced by Wythe

Francis Bacon's, Of the Advancement and Proficiencie of Learning: or, the Partitions of Sciences, Nine Books. ...

In syllogismo fit reductio propositionum ad principia per propositiones medias. Haec autem sive inveniendi sive probandi forma in scientiis popularibus (veluti ethicis, politicis, legibus, et hujusmodi) locum habet.

References

- ↑ George Wythe, Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852), 73. The subsequent Court of Appeals decision is Hill & Braxton v. Southerland's Executors, 1 Va. (1 Wash.) 128 (1792).