Difference between revisions of "Q. Horatii Flacci Opera"

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

|pages=[20], 344, [16], 353-584, 573-619, [125] | |pages=[20], 344, [16], 353-584, 573-619, [125] | ||

|desc=8vo (20 cm.) | |desc=8vo (20 cm.) | ||

| + | |shelf=J-4 | ||

}}[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horace Quintus Horatius “Horace” Flaccus] (65 BCE–8 CE) was a Roman poet about whom modern scholars actually have a good deal of information due to his own testimony and a biography by Suetonius.<ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-1556 "Horace”] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'', ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> He is unique in that all of his published works survive to this day.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Horace’s father was a freeman (a former slave) who became a successful public auctioneer, enabling Horace to go to Rome and Athens for an upper-class education.<ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192801463.001.0001/acref-9780192801463-e-1078 "Horace"] in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World'', ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).</ref> Horace was in Athens when the Roman civil war broke out after Julius Caesar’s assassination in 44 BCE, and from there he joined Brutus’ army as a military tribune from 44 to 41 BCE when (he says) he ran away from the Battle of Philippi. He “counted himself lucky to be able to return to Italy, unlike many of his comrades-in-arms,” and was accepted into a circle of writers including Maecenas, who later gave him a farm thereby securing his financial position. This security gave Horace leisure time to work on poetry (which was vastly impacted by the Sabine region in which his farm was located) and maintain his personal freedom. He declined close relationships that might commit him to others, including an influential post offer by the Emperor Augustus.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Though Horace treasured his privacy, he maintained a close friendship with Maecenas for thirty years and died several months after him without having ever married. <ref>"Horace” in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature''.</ref><br/> | }}[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horace Quintus Horatius “Horace” Flaccus] (65 BCE–8 CE) was a Roman poet about whom modern scholars actually have a good deal of information due to his own testimony and a biography by Suetonius.<ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-1556 "Horace”] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'', ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> He is unique in that all of his published works survive to this day.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Horace’s father was a freeman (a former slave) who became a successful public auctioneer, enabling Horace to go to Rome and Athens for an upper-class education.<ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192801463.001.0001/acref-9780192801463-e-1078 "Horace"] in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World'', ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).</ref> Horace was in Athens when the Roman civil war broke out after Julius Caesar’s assassination in 44 BCE, and from there he joined Brutus’ army as a military tribune from 44 to 41 BCE when (he says) he ran away from the Battle of Philippi. He “counted himself lucky to be able to return to Italy, unlike many of his comrades-in-arms,” and was accepted into a circle of writers including Maecenas, who later gave him a farm thereby securing his financial position. This security gave Horace leisure time to work on poetry (which was vastly impacted by the Sabine region in which his farm was located) and maintain his personal freedom. He declined close relationships that might commit him to others, including an influential post offer by the Emperor Augustus.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Though Horace treasured his privacy, he maintained a close friendship with Maecenas for thirty years and died several months after him without having ever married. <ref>"Horace” in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature''.</ref><br/> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| Line 28: | Line 29: | ||

View the record for this book in [https://catalog.swem.wm.edu/Record/3623429 William & Mary's online catalog]. | View the record for this book in [https://catalog.swem.wm.edu/Record/3623429 William & Mary's online catalog]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==See also== | ||

| + | *[[George Wythe Room]] | ||

| + | *''[[Oeuvres d’Horace|Oeuvres d’Horace en Latin et en Francois, avec des Remarques Critiques et Historique]]'' | ||

| + | *''[[Poetical Translation of the Works of Horace|A Poetical Translation of the Works of Horace]]'' | ||

| + | *''[[Q. Horatii Flacci Epistolae ad Pisones, et Augustum]]'' | ||

| + | *''[[Quintus Horatius Flaccus]]'' | ||

| + | *[[Wythe's Library]] | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 10:09, 4 September 2015

by Horace

| Q. Horatii Flacci Opera | |

|

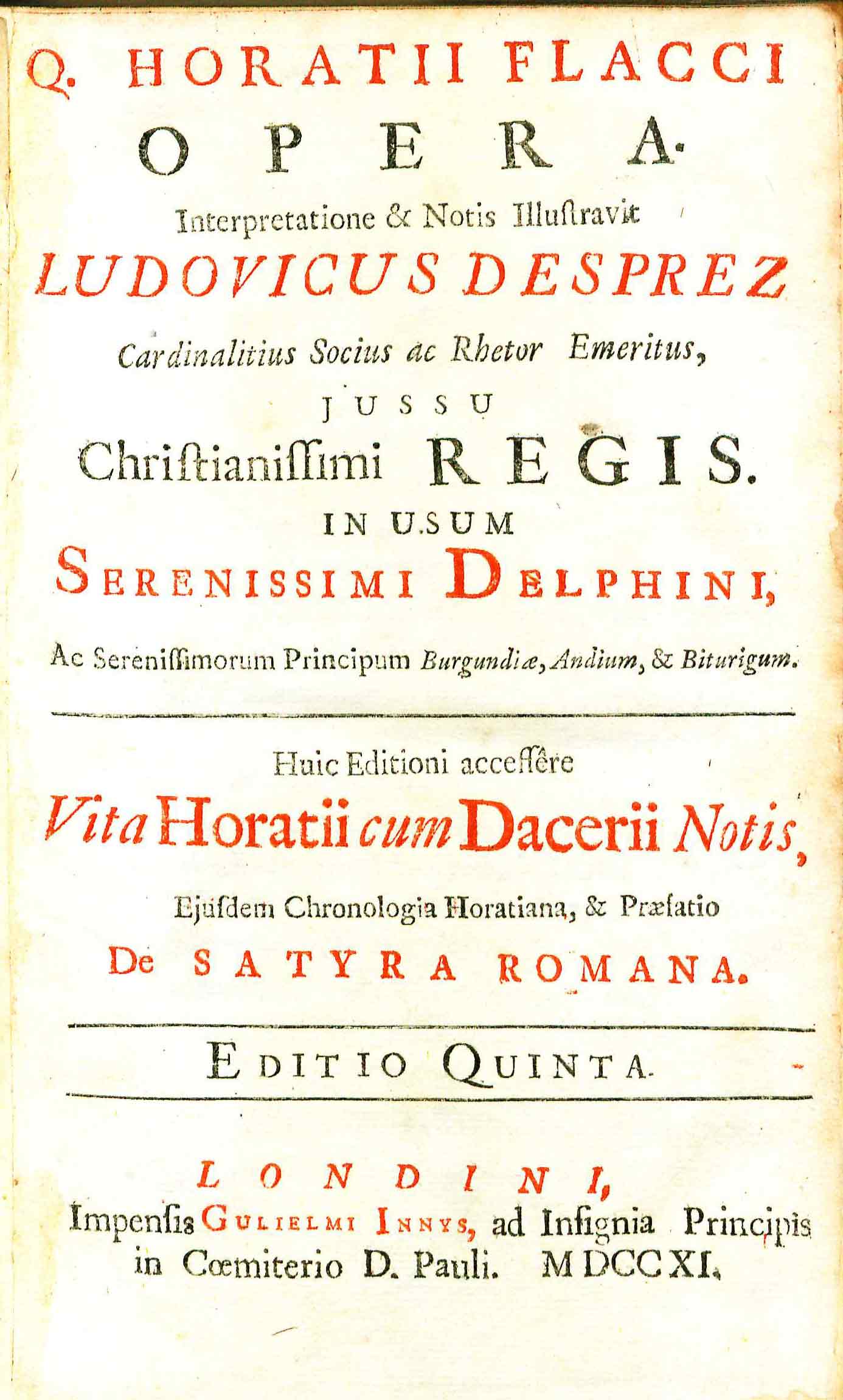

Title page from Q. Horatii Flacci Opera, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Horace |

| Editor | Louis Desprez |

| Published | Londini: Impensis Gulielmi Innys |

| Date | 1711 |

| Edition | Fifth |

| Language | Latin |

| Pages | [20], 344, [16], 353-584, 573-619, [125] |

| Desc. | 8vo (20 cm.) |

| Location | Shelf J-4 |

Quintus Horatius “Horace” Flaccus (65 BCE–8 CE) was a Roman poet about whom modern scholars actually have a good deal of information due to his own testimony and a biography by Suetonius.[1] He is unique in that all of his published works survive to this day.[2] Horace’s father was a freeman (a former slave) who became a successful public auctioneer, enabling Horace to go to Rome and Athens for an upper-class education.[3] Horace was in Athens when the Roman civil war broke out after Julius Caesar’s assassination in 44 BCE, and from there he joined Brutus’ army as a military tribune from 44 to 41 BCE when (he says) he ran away from the Battle of Philippi. He “counted himself lucky to be able to return to Italy, unlike many of his comrades-in-arms,” and was accepted into a circle of writers including Maecenas, who later gave him a farm thereby securing his financial position. This security gave Horace leisure time to work on poetry (which was vastly impacted by the Sabine region in which his farm was located) and maintain his personal freedom. He declined close relationships that might commit him to others, including an influential post offer by the Emperor Augustus.[4] Though Horace treasured his privacy, he maintained a close friendship with Maecenas for thirty years and died several months after him without having ever married. [5]

In the 30s BCE, Horace wrote and published iambic poetry collectively known as the Epodes and the Satires, and then turned to lyric poetry referred to as his Odes. It is for the “perfection of form” and “depth and detail of his self-portraiture throughout” these poems that Horace secured his “position as one of the greatest of Roman poets.”[6] His poems often addressed the key ancient topic of friendship, as well as his country and countryside, all of which he greatly loved. Horace was so well respected and his works appreciated that his Odes were used in schools before his death. He is still “the most quoted of Latin poets.”[7]

This specific work is a fifth edition of Horace’s works published in 1711 in London. It contains songs, biographies, notes, chronologies, and an index in addition to his Ars Poetica, Epodes, Satires, and Odes.

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Listed in the Jefferson Inventory of Wythe's Library as "Horatius Delphini. 8vo." and given by Thomas Jefferson to his grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph. The precise edition owned by Wythe is unknown. George Wythe's Library[8] on LibraryThing indicates this, adding "Numerous editions were published." The Brown Bibliography[9] lists the fifth edition (1711) published in London based on the copy Jefferson sold to the Library of Congress.[10] The Wolf Law Library followed Brown's suggestion and purchased the 1711 edition.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in contemporary full calf with five raised bands and gilt morocco label to spine. Covers feature blind tooling.

View the record for this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

See also

- George Wythe Room

- Oeuvres d’Horace en Latin et en Francois, avec des Remarques Critiques et Historique

- A Poetical Translation of the Works of Horace

- Q. Horatii Flacci Epistolae ad Pisones, et Augustum

- Quintus Horatius Flaccus

- Wythe's Library

References

- ↑ "Horace” in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ "Horace" in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World, ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ "Horace” in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ LibraryThing, s. v. "Member: George Wythe" accessed on February 28, 2014.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

- ↑ E. Millicent Sowerby, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, 2nd ed. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983), 4:508-509 [no.4480].