Difference between revisions of "Xenophontos Hierōn, ē Tyrannikos"

(→by Xenophon) |

(→by Xenophon) |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

|desc= | |desc= | ||

}}[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xenophon Xenophon] (c.428-c.354 BCE) was an Athenian historian and disciple of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Socrates Socrates] who had a somewhat turbulent relationship with his home city. He was born into a wealthy family and supported the short-lived oligarchic government of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Classical_Athens Athens] established in 411 BCE, which likely made it difficult for him when the democratic government was reinstated.<ref>M.C. Howatson, ed., "[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-3115 Xe'nophon] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> In 401, Xenophon joined a mercenary army and went on an expedition with the newly deceased Persian king’s son and commander [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyrus_the_Younger Cyrus the Younger] who attempted to take the throne from his older brother.<ref>M.C. Howatson, ed., "[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-0913 Cȳrus]" in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> After the failure of that attempted coup and Cyrus’s death, Xenophon returned to Greece with the rest of Cyrus’s army, for whose "lawless behavior" Xenophon was made responsible<ref>G.L. Cawkwell, "Agesilaus and Sparta," ''The Classical Quarterly'', n.s., 26, no. 1 (1976): 64.</ref> until he impressed and joined the service of Spartan king [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agesilaus_II Agesilaus] in 396 BCE and fought on the Spartan side against Athens and [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boeotia Boeotia] in 394. Either for this treachery or earlier incidents, Xenophon was exiled from Athens and his property confiscated. The Spartans gave him an estate near [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olympia,_Greece Olympia] and the position of entertaining visiting Spartans. For the next twenty years he did just that, while also writing his many books. Xenophon was forced from Olympia and moved to [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Corinth Corinth] in 371 BCE, then back to Athens in 366 BCE after all Athenians were banished from Corinth. (His exile from Athens was likely revoked around 368 BCE).<ref>Howatson, "Xe'nophon.”</ref><br/> | }}[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xenophon Xenophon] (c.428-c.354 BCE) was an Athenian historian and disciple of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Socrates Socrates] who had a somewhat turbulent relationship with his home city. He was born into a wealthy family and supported the short-lived oligarchic government of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Classical_Athens Athens] established in 411 BCE, which likely made it difficult for him when the democratic government was reinstated.<ref>M.C. Howatson, ed., "[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-3115 Xe'nophon] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> In 401, Xenophon joined a mercenary army and went on an expedition with the newly deceased Persian king’s son and commander [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyrus_the_Younger Cyrus the Younger] who attempted to take the throne from his older brother.<ref>M.C. Howatson, ed., "[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-0913 Cȳrus]" in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> After the failure of that attempted coup and Cyrus’s death, Xenophon returned to Greece with the rest of Cyrus’s army, for whose "lawless behavior" Xenophon was made responsible<ref>G.L. Cawkwell, "Agesilaus and Sparta," ''The Classical Quarterly'', n.s., 26, no. 1 (1976): 64.</ref> until he impressed and joined the service of Spartan king [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agesilaus_II Agesilaus] in 396 BCE and fought on the Spartan side against Athens and [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boeotia Boeotia] in 394. Either for this treachery or earlier incidents, Xenophon was exiled from Athens and his property confiscated. The Spartans gave him an estate near [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olympia,_Greece Olympia] and the position of entertaining visiting Spartans. For the next twenty years he did just that, while also writing his many books. Xenophon was forced from Olympia and moved to [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Corinth Corinth] in 371 BCE, then back to Athens in 366 BCE after all Athenians were banished from Corinth. (His exile from Athens was likely revoked around 368 BCE).<ref>Howatson, "Xe'nophon.”</ref><br/> | ||

| − | <br/>All known parts of the vast number of works that Xenophon produced have survived to the modern day. Most are in the three categories of "long (quasi-) historical narratives, Socratic texts, and technical treatises."<ref>John Roberts, ed., "[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192801463.001.0001/acref-9780192801463-e-2373 Xenophon]" in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).</ref> ''The Hiero'' is a Socratic dialog between a wise poet, Simonides, and Hiero, the tyrant of Syracuse. Although written in the fourth century b.c., Hiero and Simonides lived and reportedly met in the fifth century b.c.. In Xenophon’s account of the meeting, Simonides visits Hiero at his court in Syracuse. Simonides begins the discussion by questioning Hiero, who himself had previously lived as a private individual, on the relative happiness of private life compared to life as a tyrant. <ref>V. J. Gray, “Xenophon's Hiero and the Meeting of the Wise Man and Tyrant in Greek Literature,” ''The Classical Quarterly'' 36 (1986): 115-123. Accessed May 19, 2015. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0009838800010594.</ref> | + | <br/>All known parts of the vast number of works that Xenophon produced have survived to the modern day. Most are in the three categories of "long (quasi-) historical narratives, Socratic texts, and technical treatises."<ref>John Roberts, ed., "[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192801463.001.0001/acref-9780192801463-e-2373 Xenophon]" in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).</ref> ''The Hiero'' is a Socratic dialog between a wise poet, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simonides_of_Ceos Simonides of Ceos], and [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hiero_I_of_Syracuse Hiero], the tyrant of Syracuse. Although written in the fourth century b.c., Hiero and Simonides lived and reportedly met in the fifth century b.c.. In Xenophon’s account of the meeting, Simonides visits Hiero at his court in Syracuse. Simonides begins the discussion by questioning Hiero, who himself had previously lived as a private individual, on the relative happiness of private life compared to life as a tyrant. <ref>V. J. Gray, “Xenophon's Hiero and the Meeting of the Wise Man and Tyrant in Greek Literature,” ''The Classical Quarterly'' 36 (1986): 115-123. Accessed May 19, 2015. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0009838800010594.</ref> |

<br/>''The Hiero'' is comprised of two major parts. In the first section, Hiero claims that a tyrant’s life is remarkably unhappy due the burden of ruling. He attempts to convince Simonides of this viewpoint by making a series of comparisons between a tyrant’s worries and the lives of the ruled who are unconcerned by affairs of state. He even goes as far as to state that 'the tyrant can hardly do better than to hang himself.'<ref>Leo Strauss, On Tyranny, rev. edn. (London: The Free Press of Glencoe, 1963), 29.</ref> In the second, shorter section of the dialog, Simonides counters Hiero’s argument by asserting that the tyrant does in fact have a happier life than a private person because of the unique benefits and pleasures that only a ruler can experience. Simonides then gives Hiero advice on how to be a happy ruler, which entails being a ‘good king’ to the ruled. <ref>Brian Jeffrey Maxson, “Kings and tyrants: Leonardo Bruni’s translation of Xenophon’s Hiero,” ''Renaissance Studies'' 24 (2010): 188-206. Accessed May 19, 2015. DOI: 10.1111/j.1477-4658.2009.00619.x.</ref> Plato’s [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Republic_(Plato) ''Republic''], published in 380 b.c., also addresses the topic of the relative happiness between a tyrant and a private person. Although both works employ the Socratic style, ''The Hiero'', unlike Plato's [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Republic_(Plato) ''Republic''], is not a regular Socratic dialog because it does not feature Socrates as a character in the text. <ref>Gray, “Xenophon's Hiero and the Meeting of the Wise Man and Tyrant in Greek Literature.”</ref> | <br/>''The Hiero'' is comprised of two major parts. In the first section, Hiero claims that a tyrant’s life is remarkably unhappy due the burden of ruling. He attempts to convince Simonides of this viewpoint by making a series of comparisons between a tyrant’s worries and the lives of the ruled who are unconcerned by affairs of state. He even goes as far as to state that 'the tyrant can hardly do better than to hang himself.'<ref>Leo Strauss, On Tyranny, rev. edn. (London: The Free Press of Glencoe, 1963), 29.</ref> In the second, shorter section of the dialog, Simonides counters Hiero’s argument by asserting that the tyrant does in fact have a happier life than a private person because of the unique benefits and pleasures that only a ruler can experience. Simonides then gives Hiero advice on how to be a happy ruler, which entails being a ‘good king’ to the ruled. <ref>Brian Jeffrey Maxson, “Kings and tyrants: Leonardo Bruni’s translation of Xenophon’s Hiero,” ''Renaissance Studies'' 24 (2010): 188-206. Accessed May 19, 2015. DOI: 10.1111/j.1477-4658.2009.00619.x.</ref> Plato’s [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Republic_(Plato) ''Republic''], published in 380 b.c., also addresses the topic of the relative happiness between a tyrant and a private person. Although both works employ the Socratic style, ''The Hiero'', unlike Plato's [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Republic_(Plato) ''Republic''], is not a regular Socratic dialog because it does not feature Socrates as a character in the text. <ref>Gray, “Xenophon's Hiero and the Meeting of the Wise Man and Tyrant in Greek Literature.”</ref> | ||

Revision as of 14:56, 19 May 2015

by Xenophon

| Xenophontos Hieron, e Tyrannikos | ||

|

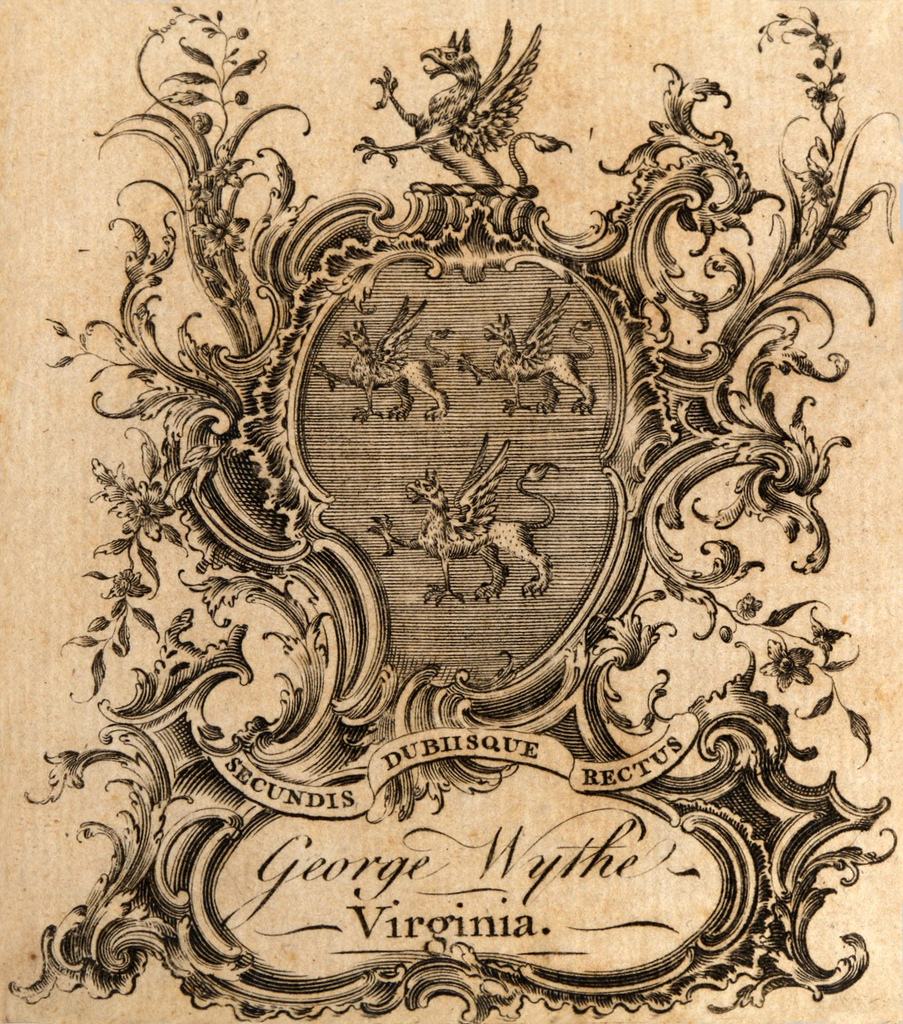

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | Xenophon | |

| Published | Glasguæ: in Aedibus Academicis Excudebat R. Foulis, Academiae Typographus | |

| Date | 1745 | |

| Language | Greek and Latin | |

Xenophon (c.428-c.354 BCE) was an Athenian historian and disciple of Socrates who had a somewhat turbulent relationship with his home city. He was born into a wealthy family and supported the short-lived oligarchic government of Athens established in 411 BCE, which likely made it difficult for him when the democratic government was reinstated.[1] In 401, Xenophon joined a mercenary army and went on an expedition with the newly deceased Persian king’s son and commander Cyrus the Younger who attempted to take the throne from his older brother.[2] After the failure of that attempted coup and Cyrus’s death, Xenophon returned to Greece with the rest of Cyrus’s army, for whose "lawless behavior" Xenophon was made responsible[3] until he impressed and joined the service of Spartan king Agesilaus in 396 BCE and fought on the Spartan side against Athens and Boeotia in 394. Either for this treachery or earlier incidents, Xenophon was exiled from Athens and his property confiscated. The Spartans gave him an estate near Olympia and the position of entertaining visiting Spartans. For the next twenty years he did just that, while also writing his many books. Xenophon was forced from Olympia and moved to Corinth in 371 BCE, then back to Athens in 366 BCE after all Athenians were banished from Corinth. (His exile from Athens was likely revoked around 368 BCE).[4]

All known parts of the vast number of works that Xenophon produced have survived to the modern day. Most are in the three categories of "long (quasi-) historical narratives, Socratic texts, and technical treatises."[5] The Hiero is a Socratic dialog between a wise poet, Simonides of Ceos, and Hiero, the tyrant of Syracuse. Although written in the fourth century b.c., Hiero and Simonides lived and reportedly met in the fifth century b.c.. In Xenophon’s account of the meeting, Simonides visits Hiero at his court in Syracuse. Simonides begins the discussion by questioning Hiero, who himself had previously lived as a private individual, on the relative happiness of private life compared to life as a tyrant. [6]

The Hiero is comprised of two major parts. In the first section, Hiero claims that a tyrant’s life is remarkably unhappy due the burden of ruling. He attempts to convince Simonides of this viewpoint by making a series of comparisons between a tyrant’s worries and the lives of the ruled who are unconcerned by affairs of state. He even goes as far as to state that 'the tyrant can hardly do better than to hang himself.'[7] In the second, shorter section of the dialog, Simonides counters Hiero’s argument by asserting that the tyrant does in fact have a happier life than a private person because of the unique benefits and pleasures that only a ruler can experience. Simonides then gives Hiero advice on how to be a happy ruler, which entails being a ‘good king’ to the ruled. [8] Plato’s Republic, published in 380 b.c., also addresses the topic of the relative happiness between a tyrant and a private person. Although both works employ the Socratic style, The Hiero, unlike Plato's Republic, is not a regular Socratic dialog because it does not feature Socrates as a character in the text. [9]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

References

- ↑ M.C. Howatson, ed., "Xe'nophon in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- ↑ M.C. Howatson, ed., "Cȳrus" in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- ↑ G.L. Cawkwell, "Agesilaus and Sparta," The Classical Quarterly, n.s., 26, no. 1 (1976): 64.

- ↑ Howatson, "Xe'nophon.”

- ↑ John Roberts, ed., "Xenophon" in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- ↑ V. J. Gray, “Xenophon's Hiero and the Meeting of the Wise Man and Tyrant in Greek Literature,” The Classical Quarterly 36 (1986): 115-123. Accessed May 19, 2015. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0009838800010594.

- ↑ Leo Strauss, On Tyranny, rev. edn. (London: The Free Press of Glencoe, 1963), 29.

- ↑ Brian Jeffrey Maxson, “Kings and tyrants: Leonardo Bruni’s translation of Xenophon’s Hiero,” Renaissance Studies 24 (2010): 188-206. Accessed May 19, 2015. DOI: 10.1111/j.1477-4658.2009.00619.x.

- ↑ Gray, “Xenophon's Hiero and the Meeting of the Wise Man and Tyrant in Greek Literature.”