Difference between revisions of "Office and Duty of Executors"

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

|publoc= | |publoc= | ||

|publisher= | |publisher= | ||

| − | |year=Precise edition unknown. | + | |year= |

| − | + | |edition=Precise edition unknown. | |

|lang= | |lang= | ||

|set= | |set= | ||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

}}[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Wentworth_%28Recorder_of_Oxford%29 Thomas Wentworth] (1567/8-1628), was a lawyer and politician, and the son of Peter Wentworth, the Elizabethan parliamentarian.<ref>Maija Jansson, "[http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/29055 Wentworth, Thomas (1567/8-1628)]," ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford University Press, 2004-), accessed on February 20, 2015.</ref> Wentworth attended University College, Oxford in 1584; and in 1585, he entered [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lincoln%27s_Inn Lincoln’s Inn], where he was appointed Lent reader in 1612 and treasurer in 1621.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Wentworth married into a puritan family, and puritanism remained a central theme throughout his life and parliamentary career.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Wentworth was outspoken against crown policy, including being opposed to the proposed act of union with Scotland. Wentworth also believed the law was superior to the king, saying, "If the King have a power over the laws, we cannot have security, therefore we must see if the law can bind the King."<ref>Ibid.</ref> King James wished to punish Wentworth for his speeches, but was dissuaded at the time by the Privy Council.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Wentworth was finally imprisoned in the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tower Tower] in 1614, justified by the King by claiming Wentworth had offended the French ambassador, after a speech arguing against impositions.<ref>Ibid.</ref> He asserted "that in all ages the King’s prerogative…hathe bene examined and debated in Parliament."<ref>Harold Hulme, "The Winning of Freedom of Speech by the House of Commons," ''The American Historical Review'' 61, no. 4 (Jul. 1956): 832.</ref> He further opposed Spanish marriage for the King, arguing that a catholic queen would be problematic, and wanted a protestant wife to ensure protestant succession. Wentworth died in March or April 1628 in Henley.<ref>Jansson, "Wenthworth, Thomas (1567/8-1628)."</ref><br /> | }}[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Wentworth_%28Recorder_of_Oxford%29 Thomas Wentworth] (1567/8-1628), was a lawyer and politician, and the son of Peter Wentworth, the Elizabethan parliamentarian.<ref>Maija Jansson, "[http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/29055 Wentworth, Thomas (1567/8-1628)]," ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford University Press, 2004-), accessed on February 20, 2015.</ref> Wentworth attended University College, Oxford in 1584; and in 1585, he entered [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lincoln%27s_Inn Lincoln’s Inn], where he was appointed Lent reader in 1612 and treasurer in 1621.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Wentworth married into a puritan family, and puritanism remained a central theme throughout his life and parliamentary career.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Wentworth was outspoken against crown policy, including being opposed to the proposed act of union with Scotland. Wentworth also believed the law was superior to the king, saying, "If the King have a power over the laws, we cannot have security, therefore we must see if the law can bind the King."<ref>Ibid.</ref> King James wished to punish Wentworth for his speeches, but was dissuaded at the time by the Privy Council.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Wentworth was finally imprisoned in the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tower Tower] in 1614, justified by the King by claiming Wentworth had offended the French ambassador, after a speech arguing against impositions.<ref>Ibid.</ref> He asserted "that in all ages the King’s prerogative…hathe bene examined and debated in Parliament."<ref>Harold Hulme, "The Winning of Freedom of Speech by the House of Commons," ''The American Historical Review'' 61, no. 4 (Jul. 1956): 832.</ref> He further opposed Spanish marriage for the King, arguing that a catholic queen would be problematic, and wanted a protestant wife to ensure protestant succession. Wentworth died in March or April 1628 in Henley.<ref>Jansson, "Wenthworth, Thomas (1567/8-1628)."</ref><br /> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| − | ''The Office and Duty of Executors'', ascribed to Wentworth, is a book directed at both testators and executors in the course of their duties. Wentworth, in the preface, explained that there was little that was more important and useful than to understand the laws and duties of the office of executors.<ref>Thomas Wentworth, ''[https://archive.org/details/officedutyofexec00went The Office and Duty of Executors]'' (London: Printed by John Streater, James Flesher, and Henry Twyford, assigns of Richard Atkyns and Edward Atkyns, Esquires, 1668), Preface, paragraph 11.</ref> According to the author, three parts are necessary to understand this law: (1) their being | + | ''The Office and Duty of Executors'', ascribed to Wentworth, is a book directed at both testators and executors in the course of their duties. Wentworth, in the preface, explained that there was little that was more important and useful than to understand the laws and duties of the office of executors.<ref>Thomas Wentworth, ''[https://archive.org/details/officedutyofexec00went The Office and Duty of Executors]'' (London: Printed by John Streater, James Flesher, and Henry Twyford, assigns of Richard Atkyns and Edward Atkyns, Esquires, 1668), Preface, paragraph 11.</ref> According to the author, three parts are necessary to understand this law: (1) their being—the creation or constitution of the executor, (2) their having—the executor's "interest, fruition, or possession," and (3) their doing—the managing and execution of the executor’s office. The latter is the focus of the work. Wentworth emphasizes the need to go through all three parts to understand the law, using an analogy to a trip, where you must pass through all other towns and villages.<ref>Ibid., 1.</ref> |

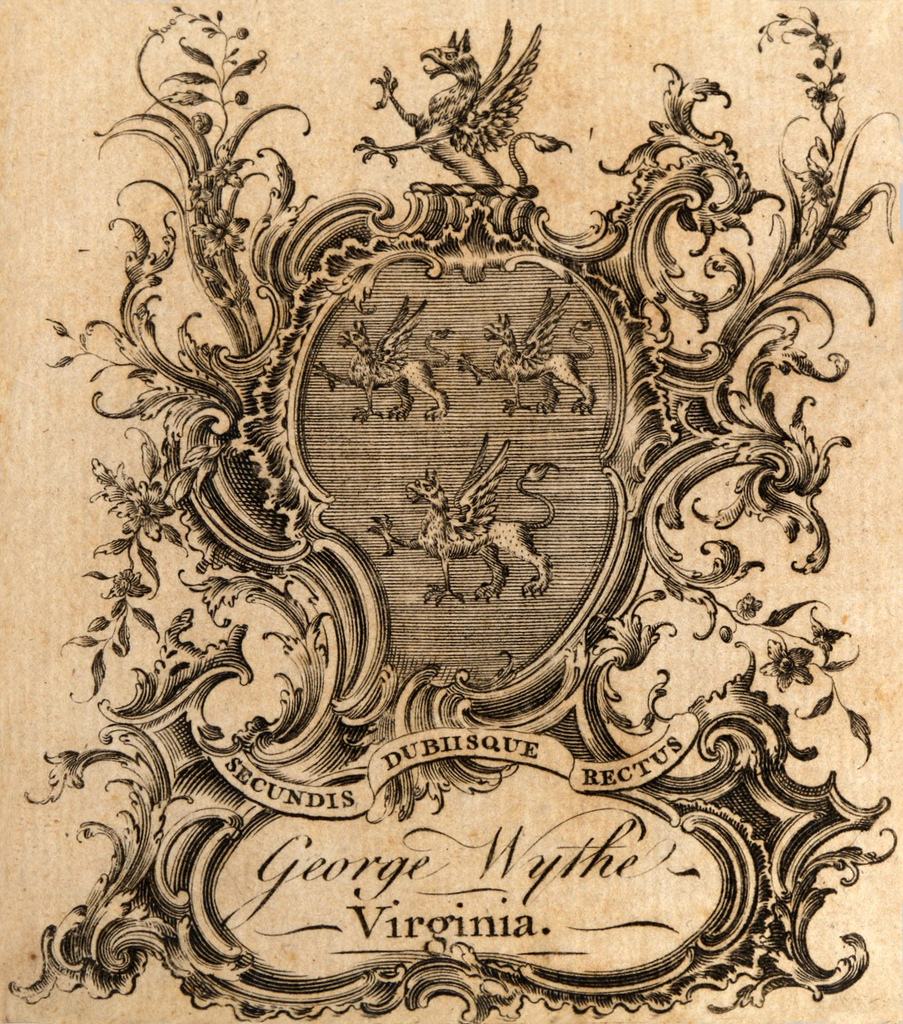

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

| − | The [https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433 Brown Bibliography]<ref> Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012, rev. 2014) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433</ref> suggests Wythe owned the 1763 edition of ''The Office and Duty of Executors'' based on entries in the manuscript copy of John Marshall's commonplace book. Brown also notes that Wythe referenced Wentworth's treatise in his arguments for ''[[Bolling v. Bolling]]'' in the section of the first argument for the plaintiff in which he anticipates Jefferson's use of various legal sources. Wythe writes: | + | The [https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433 Brown Bibliography]<ref> Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012, rev. 2014) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433</ref> suggests Wythe owned the 1763 edition of ''The Office and Duty of Executors'' based on entries in the manuscript copy of John Marshall's commonplace book. Brown also notes that Wythe referenced Wentworth's treatise in his arguments for ''[[Bolling v. Bolling]]''. Wythe's reference occurs in the section of the first argument for the plaintiff in which he anticipates Jefferson's use of various legal sources. Wythe writes: |

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| − | Obj. Wentworth's office of executor pa. 59. 'put the case that a man dies in July &c. — all these shall pass to one to whom the land is sold or conveied, if not excepted, though never so near reaping, felling or gathering.' | + | Obj. Wentworth's office of executor pa. 59. 'put the case that a man dies in July &c. — all these shall pass to one to whom the land is sold or conveied, if not excepted, though never so near reaping, felling or gathering.'<br /> |

| + | <br /> | ||

Ans. Wentworth was a compiler only, and what he sais of the sale or conveiance, since he quotes no authority is but his opinion, which was probably founded upon that leading case in Cro. El. 61.<ref>Bernard Schwartz, Barbara Wilcie Kern, R. B. Bernstein, eds., ''Thomas Jefferson and Bolling v. Bolling: Law and the Legal Profession in Pres-Revolutionary America'' (San Marino, CA: The Huntington Library; New York: New York University School of Law, 1997), 155.</ref> | Ans. Wentworth was a compiler only, and what he sais of the sale or conveiance, since he quotes no authority is but his opinion, which was probably founded upon that leading case in Cro. El. 61.<ref>Bernard Schwartz, Barbara Wilcie Kern, R. B. Bernstein, eds., ''Thomas Jefferson and Bolling v. Bolling: Law and the Legal Profession in Pres-Revolutionary America'' (San Marino, CA: The Huntington Library; New York: New York University School of Law, 1997), 155.</ref> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| + | Neither Wythe's reference in ''Bolling v. Bolling'' nor Marshall's commonplace book indicate a particular edition. | ||

| + | |||

The Wolf Law Library has not yet added a copy of Wentworth's ''The Office and Duty of Executors''. | The Wolf Law Library has not yet added a copy of Wentworth's ''The Office and Duty of Executors''. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 09:59, 5 March 2015

The Office and Duty of Executors: or, A Treatise of Wills and Executors, directed to Testators

by Thomas Wentworth

| The Office and Duty of Executors | ||

|

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Author | Thomas Wentworth | |

| Edition | Precise edition unknown. | |

Thomas Wentworth (1567/8-1628), was a lawyer and politician, and the son of Peter Wentworth, the Elizabethan parliamentarian.[1] Wentworth attended University College, Oxford in 1584; and in 1585, he entered Lincoln’s Inn, where he was appointed Lent reader in 1612 and treasurer in 1621.[2] Wentworth married into a puritan family, and puritanism remained a central theme throughout his life and parliamentary career.[3] Wentworth was outspoken against crown policy, including being opposed to the proposed act of union with Scotland. Wentworth also believed the law was superior to the king, saying, "If the King have a power over the laws, we cannot have security, therefore we must see if the law can bind the King."[4] King James wished to punish Wentworth for his speeches, but was dissuaded at the time by the Privy Council.[5] Wentworth was finally imprisoned in the Tower in 1614, justified by the King by claiming Wentworth had offended the French ambassador, after a speech arguing against impositions.[6] He asserted "that in all ages the King’s prerogative…hathe bene examined and debated in Parliament."[7] He further opposed Spanish marriage for the King, arguing that a catholic queen would be problematic, and wanted a protestant wife to ensure protestant succession. Wentworth died in March or April 1628 in Henley.[8]

The Office and Duty of Executors, ascribed to Wentworth, is a book directed at both testators and executors in the course of their duties. Wentworth, in the preface, explained that there was little that was more important and useful than to understand the laws and duties of the office of executors.[9] According to the author, three parts are necessary to understand this law: (1) their being—the creation or constitution of the executor, (2) their having—the executor's "interest, fruition, or possession," and (3) their doing—the managing and execution of the executor’s office. The latter is the focus of the work. Wentworth emphasizes the need to go through all three parts to understand the law, using an analogy to a trip, where you must pass through all other towns and villages.[10]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

The Brown Bibliography[11] suggests Wythe owned the 1763 edition of The Office and Duty of Executors based on entries in the manuscript copy of John Marshall's commonplace book. Brown also notes that Wythe referenced Wentworth's treatise in his arguments for Bolling v. Bolling. Wythe's reference occurs in the section of the first argument for the plaintiff in which he anticipates Jefferson's use of various legal sources. Wythe writes:

Obj. Wentworth's office of executor pa. 59. 'put the case that a man dies in July &c. — all these shall pass to one to whom the land is sold or conveied, if not excepted, though never so near reaping, felling or gathering.'

Ans. Wentworth was a compiler only, and what he sais of the sale or conveiance, since he quotes no authority is but his opinion, which was probably founded upon that leading case in Cro. El. 61.[12]

Neither Wythe's reference in Bolling v. Bolling nor Marshall's commonplace book indicate a particular edition.

The Wolf Law Library has not yet added a copy of Wentworth's The Office and Duty of Executors.

References

- ↑ Maija Jansson, "Wentworth, Thomas (1567/8-1628)," Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004-), accessed on February 20, 2015.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Harold Hulme, "The Winning of Freedom of Speech by the House of Commons," The American Historical Review 61, no. 4 (Jul. 1956): 832.

- ↑ Jansson, "Wenthworth, Thomas (1567/8-1628)."

- ↑ Thomas Wentworth, The Office and Duty of Executors (London: Printed by John Streater, James Flesher, and Henry Twyford, assigns of Richard Atkyns and Edward Atkyns, Esquires, 1668), Preface, paragraph 11.

- ↑ Ibid., 1.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012, rev. 2014) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

- ↑ Bernard Schwartz, Barbara Wilcie Kern, R. B. Bernstein, eds., Thomas Jefferson and Bolling v. Bolling: Law and the Legal Profession in Pres-Revolutionary America (San Marino, CA: The Huntington Library; New York: New York University School of Law, 1997), 155.