Difference between revisions of "Memoirs of the Late George Wythe, Esquire"

(→Article text) |

(→Article text) |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

This true grandeur of mind, so closely resembling that of the ancient Fabricius, Curius, and Cincinatus, he uniformly preserved to the end of his life. His manner of living was plain and abstemious; for he found the means of becoming superior to the love of wealth by limiting the number of his wants. An ardent desire to promote the happiness of his fellow-men, by supporting the cause of justice, and maintaining and establishing their rights, appears to have been his only ruling passion. How unfortunate is it for the human race that this angelic disposition is so uncommon among men, that the multitude are bent on nothing but projects of obtaining riches or honors, without any regard to the common good! How particularly deplorable, that in the United States of America, (now the last hope of republicanism) a grovelling spirit of avarice, or, at least, too great a fondness for lucre, appears generally to prevail, instead of that disinterested love of country, which warmed the bosoms of the sages and heroes of Greece and Rome, and existed in none of ''them'' with more energy than in the venerable Wythe!—The prevalence of that spirit among us, it is to be feared, is ominous of the downfall of our republican institutions, and, unless it be repressed by some change in the public mind, that cannot now be forseen, will sooner or later have that effect;—the best method of preventing which must be the establishment of a wise and general system of education. | This true grandeur of mind, so closely resembling that of the ancient Fabricius, Curius, and Cincinatus, he uniformly preserved to the end of his life. His manner of living was plain and abstemious; for he found the means of becoming superior to the love of wealth by limiting the number of his wants. An ardent desire to promote the happiness of his fellow-men, by supporting the cause of justice, and maintaining and establishing their rights, appears to have been his only ruling passion. How unfortunate is it for the human race that this angelic disposition is so uncommon among men, that the multitude are bent on nothing but projects of obtaining riches or honors, without any regard to the common good! How particularly deplorable, that in the United States of America, (now the last hope of republicanism) a grovelling spirit of avarice, or, at least, too great a fondness for lucre, appears generally to prevail, instead of that disinterested love of country, which warmed the bosoms of the sages and heroes of Greece and Rome, and existed in none of ''them'' with more energy than in the venerable Wythe!—The prevalence of that spirit among us, it is to be feared, is ominous of the downfall of our republican institutions, and, unless it be repressed by some change in the public mind, that cannot now be forseen, will sooner or later have that effect;—the best method of preventing which must be the establishment of a wise and general system of education. | ||

| − | With respect to the practice of receiving more than legal fees, which now prevails among the lawyers in Virginia, it may be indeed | + | With respect to the practice of receiving more than legal fees, which now prevails among the lawyers in Virginia, it may be indeed be said that the change in the value of money has made those fees totally inadequate to their ''support:'' but it ought to be observed that the noble profession of dealing out law and justice to the people should not be followed for the sake of ''gain.'' The fees ought ''now'' to be increased, so as to furnish a moderate and reasonable compensation for the necessary services of men of talents; but every gentleman of the bar should also be a farmer or planter, or should have some other resource, from which, and, not from those unfortunately involved in debts and disputes, a part of his support should be derived; to enable him to accomplish which, he should in his youth, be instructed in agriculture as well as law; should be taught to devote a portion of his time to literary pursuits should attend a very small number of courts as an attorney; and, above all, should, like the frugal and noble-minded Wythe, be content with a little. |

<center>''To be Continued.''</center></blockquote> | <center>''To be Continued.''</center></blockquote> | ||

Revision as of 15:12, 7 March 2013

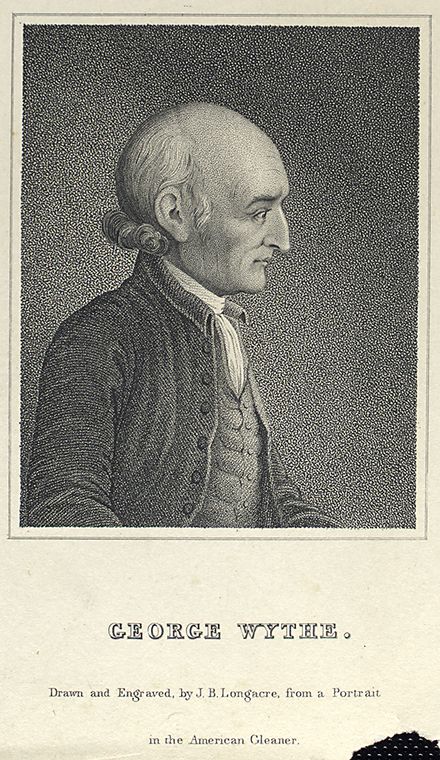

"Memoirs of the Late George Wythe, Esquire" is a tribute which appeared in the first issue of the The American Gleaner and Virginia Magazine, published in Richmond, Virginia. The magazine debuted on Saturday, January 24, 1807, seven months after Wythe's death. The article was published without a byline and the author remains anonymous.

Article text

For the AMERICAN GLEANER.

MEMOIRS

OF THE LATE

GEORGE WYTHE, ESQUIRE.

[with a correct likeness.]The fame of the disturbers and destroyers of mankind is generally sounded very loudly by poets and historians, while the names of the peaceful benefactors of their species, of those who were noted only for virtue and wisdom, are often suffered silently to sink into oblivion. But to this observation, which, unfortunately, for the honor of human nature is to true, there have been some exceptions. The glory of Socrates although not preserved by any writings of his own, has been as lasting as that of Cæsar or Alexander; and may we not hope that the modest but truly rare and extraordinary merit of GEORGE WYTHE, the Virginian Socrates, may obtain for him a niche in the temple of immortality? At any rate it is the duty of the American biographer, who reveres republican virtue, to endeavor to commemorate it as a useful example for the imitation of his countrymen. It is his duty to give the small tribute of his applause to a perfect model of integrity, and republican purity, to the man, who dedicated almost fifty years of his life, with indefatigable diligence to the service of his country.

GEORGE WYTHE, the subject of these memoirs was born in Elizabeth City in the year 1726. His father was a respectable farmer in middling circumstances, and not remarkable for the extent of his abilities or information; but his mother was a woman of uncommon knowledge and strength of mind. She was immediately acquainted with the Latin language, which she spoke fluently, and taught her son. His education in other respects was very much neglected: for he has often informed the author of these memoirs, that he was taught at school nothing more than reading and writing English, and the five first rules of Arithmetic. Such were the only instructions he received, who, nevertheless, by the dint of his own unwearied application, became afterwards one of the most learned men in America! His first appearance on the stage of life, however, promised a character by no means similar to that which he afterwards exhibited. His parents having died before he attained the of twenty one years, he launched, on commencing the world, as unthinking youths are apt to do, into a career of dissipation and intemperance, from which he did not disengage himself until he attained his thirtieth year. I have often heard him pathetically lament the loss of those nine years of his life, and of the knowledge which might have been acquired by employing them, as well as those which succeeded them in study. But never did any man more effectually redeem his time, from the moment when he resolved on reformation. His life was devoted to the most intense application; and, without the assistance of any instructor, he taught himself Greek of which he acquired a most accurate knowledge; and read all the best authors in that as well as in the Latin language: He made himself also a profound lawyer, perfectly versed in the civil and common law, and in the statutes of Great Britain and Virginia; a skilful mathematician, and well acquainted with moral and natural philosophy. A most remarkable example of the effect of patient industry and attention, and of a complete contrast in the character of the same individual at different periods of his life! The wild and thought less youth was now converted into a sedate and prudent man, delighting entirely in literary pursuits, and walking only in the paths of wisdom. At this period he acquired that attachment to the Christian religion and reverence for its truths, which, although his faith was afterwards shaken by the difficulties suggested by sceptical writers, never altogether forsook him, and towards the close of his life was renovated and firmly established. For many years he constantly attended church, and the bible was his favourite book, as he has often informed the author. But he never connected himself with any sect of Christians, being of the opinion that every sect had more or less corrupted the purity of the system of religion taught in the scriptures, and being an utter enemy to all intolerance and pretences to exclusive holiness. He thought that all good men would be entitled to a seat in the kingdom of Heaven, and endeavored by his own upright and benevolent conduct to deserve one himself. Having obtained a licence to practice law, he took his station at the bar of the old general court with many other great men, whose merit is well known to have been the boast of Virginia. Among them he was conspicuous, not for his eloquence, or ingenuity in maintaining a bad cause, but for his sound sense and learning and rigid attachment to justice. Certain it is, however, strange as it may seem to the lawyers of the present day, that he never undertook the support of a cause which he knew to be bad, and, if he discovered his client had deceived him, returned him the fee and forsook it. This happened however, very seldom, as he was extremely particular in questioning every person who applied to employ him, and would not engage in his business unless it appeared to be just and honorable. He has even been known, where he entertained doubts, to insist on his client's making an affidavit to the truth of his statement of the circumstances of his case, and, in every instance, where it was in his power, he examined the witnesses, as to the facts intended to be proved, before he brought the suit, or agreed to defend it. If the gentlemen of the bar would always follow this rule, how much injustice and oppression would be prevented, how much troublesome and useless litigation would be avoided!

His strict obedience to the laws of his country, and his disinterested contempt of money were no less remarkable than his sacred regard to equity. On all occasions he refused to receive more than his legal fee, even where he had gained a cause, and his client made him a voluntary offer of an extraordinary but well merited compensation.—When offers of this kind were made him, he would say that the labourer was indeed worthy of his hire, but the lawful fee was all he had a right to demand, and, as to presents, he did not want and would not accept them from any man.

This true grandeur of mind, so closely resembling that of the ancient Fabricius, Curius, and Cincinatus, he uniformly preserved to the end of his life. His manner of living was plain and abstemious; for he found the means of becoming superior to the love of wealth by limiting the number of his wants. An ardent desire to promote the happiness of his fellow-men, by supporting the cause of justice, and maintaining and establishing their rights, appears to have been his only ruling passion. How unfortunate is it for the human race that this angelic disposition is so uncommon among men, that the multitude are bent on nothing but projects of obtaining riches or honors, without any regard to the common good! How particularly deplorable, that in the United States of America, (now the last hope of republicanism) a grovelling spirit of avarice, or, at least, too great a fondness for lucre, appears generally to prevail, instead of that disinterested love of country, which warmed the bosoms of the sages and heroes of Greece and Rome, and existed in none of them with more energy than in the venerable Wythe!—The prevalence of that spirit among us, it is to be feared, is ominous of the downfall of our republican institutions, and, unless it be repressed by some change in the public mind, that cannot now be forseen, will sooner or later have that effect;—the best method of preventing which must be the establishment of a wise and general system of education.

With respect to the practice of receiving more than legal fees, which now prevails among the lawyers in Virginia, it may be indeed be said that the change in the value of money has made those fees totally inadequate to their support: but it ought to be observed that the noble profession of dealing out law and justice to the people should not be followed for the sake of gain. The fees ought now to be increased, so as to furnish a moderate and reasonable compensation for the necessary services of men of talents; but every gentleman of the bar should also be a farmer or planter, or should have some other resource, from which, and, not from those unfortunately involved in debts and disputes, a part of his support should be derived; to enable him to accomplish which, he should in his youth, be instructed in agriculture as well as law; should be taught to devote a portion of his time to literary pursuits should attend a very small number of courts as an attorney; and, above all, should, like the frugal and noble-minded Wythe, be content with a little.

To be Continued.