"George Wythe Courts the Muses: In Which, to the Astonishment of Everyone, That Silent, Selfless Pedant Is Found to Have Had a Sense of Humor"

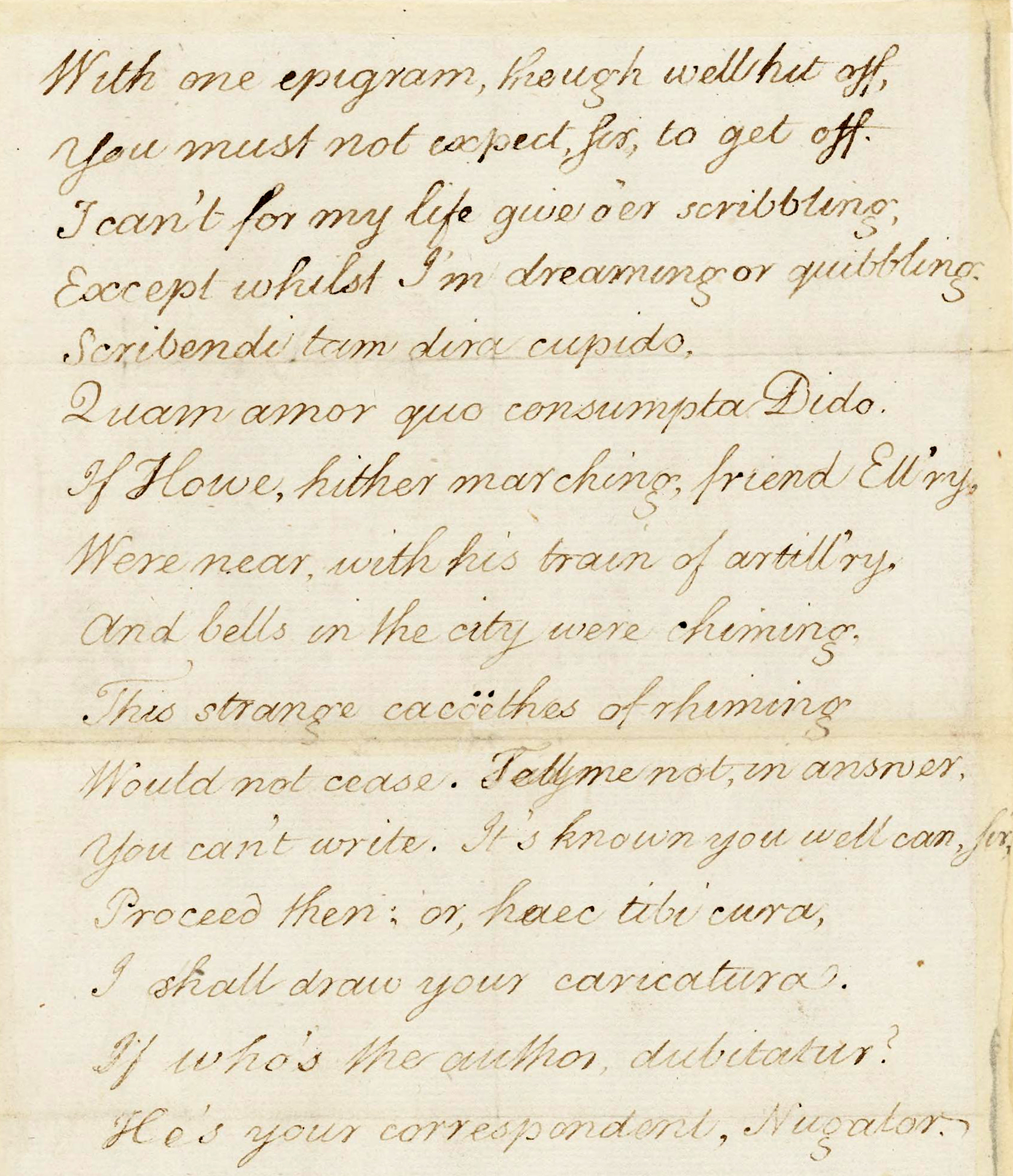

Poem by George Wythe (VA), addressing William Ellery (RI), written during the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, 1776. From Poems on Witty Subjects in Congress, in the Boston Public Library's American Revolutionary War Manuscript Collection.

With one epigram, though well hit off,

You must not expect, Sir, to get off.

I can't for my life give o'er scribbling,

Except whilst I'm dreaming or quibbling.

Scribendi tam dira cupido,

Quam amor quo consumpta Dido.

If Howe, hither marching, friend Ell'ry,

Were near with his train of artill'ry

And bells in the city were chiming,

This strange cacoëthes of rhiming

Would not cease. Tell me not, in answer,

You can't write. It's known you well can, Sir,

Proceed then; or haec tibi cura,

I shall draw your caricatura.

If who's the author, dubitatur?

He's your correspondent, Nugator.

In the early 1950s, W. Edwin Hemphill discovered a series of notes in verse written in 1776,[1] exchanged between George Wythe, delegate from Virginia, and William Ellery, delegate from Rhode Island, during the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia. The poems were in the American Revolutionary War Manuscripts Collection at the Boston Public Library, in Massachusetts. Hemphill detailed the contents of the discovery in an article in the William and Mary Quarterly, in 1952.[2]

Contents

[hide]Article text, July 1952

Page 338

George Wythe Courts the Muses:

In Which, to the Astonishment of Everyone, That Silent, Selfless Pedant Is Found to Have Had a Sense of Humor

W. Edwin Hemphill*THE personality of a man can undergo an about-face as he grows older. The affable and extrovert may become silent and introvert. A serious outlook may replace lightheartedness. Gravity may supplant wit. Such a transformation seems to have occurred between the fiftieth and eightieth birthdays of George Wythe of Virginia.

During his last fifteen years this solitary old man, then a widower for the second time, lived with three freed Negro servants in a modest frame building. He had no really near neighbor. His house stood on a lot which constituted a quarter of a partially vacant block in what is now the teeming heart of Richmond's downtown shopping area. When he died under peculiarly tragic circumstances on June 6, 1806 [sic],[3] this mellow but uncommunicative octogenarian was survived by no closer kinsmen than the grandchildren of his sister. Only a few intimates had in recent years years enjoyed his friendship, though he was admired by all who knew him personally or were acquainted with his reputation.

Tolerantly, even affectionately, people told of his idiosyncrasies in which, they felt, he had earned the right to be indulged. They spoke of his habit of ushering into his equity court's office without so much as a word for those who called on business, of how he received courteously but with nothing other a knowing and reassuring air the papers concerning their cases, and of how they were dismissed silently but with what Henry Clay described late in his life as the courtliest bow he had ever seen. Wythe's wordless visit to a Richmond bakery to purchase each time a single loaf of bread and the daily ritual at his backyard well of his early morning sponge bath, for which he stripped to his waist even in the coldest winter weather—these and other eccentricities had become legendary. They gave him a Quaker-like reputation for simplicity and austerity.

* Mr. Hemphill is editor of Virginia Cavalcade and a member of the staff of the Virginia State Library.

Page 339

But was there ever so selfless a public servant? Had he not been for more than half a century an honest lawyer and incorruptible judge, a progressive colonial and state legislator and a patriotic Congressman, a man of wealth whom the Revolution and the state's penurious salaries had impoverished? Nevertheless, had he not emancipated his slaves? Was he not the generous but secret benefactor of the needy and the young of both races? Had he not taught and befriended a whole generation of attorneys and statesmen ranging from Thomas Jefferson to Henry Clay? Surely, people had agreed, such an incomparable citizen was entitled to the peaceable practice of a few foibles in his still useful but inevitably few remaining years of slavish labor for the common weal!

These may have been some of the sad reflections which prompted the anonymous contributor of an obituary portrait of George Wythe to honor him with what the writer undoubtedly considered to be a glowing tribute: "Wit he never aimed at, because he did not possess it; he had a turn of mind too lofty for humor."1

We can concede the good intentions of this admirer of "the American Aristides." But we must disagree with this portion of his eulogy of George Wythe. Charitably, we can suppose that he was a younger man who had not known the personality of the Wythe who had enjoyed a livelier, more sociable middle age. For in an obscure collection of old manuscripts, the Chamberlain Papers in the Boston Public Library, I have discovered (as, apparently no one else ever has) unexpected but undeniable proof in his own handwriting that the sedate and self-contained Wythe of eighty had earlier possessed an overflowing sense of humor. I shall let you see in this article some of this evidence of Wythe's hitherto unsuspected ability to extract fun from a dull situation. For your ease in reading this obsolete style of poetry, I shall condense it slightly, chiefly to omit various classical phrases and allusions, and shall modernize its spelling, capitalization, and punctuation.

The year 1776 brought to our forefathers times which, in Thomas Paine's oft-quoted phrase, "tried men's souls." We usually like to think of our statesmen's earnest seriousness and stolid defiance in facing the manifold problems of its hours of crisis. But we can take our patriots off their pedestals without disparagement to their cold, impersonal reputations as statesmen. If we do so, we're likely to find that they were warm,1 Anonymous, "Communication," Richmond Virginia Argus, June 9, 1806 [sic].[4]

Page 340

very human beings. The fact that they sometimes made jokes of public issues and jealousies.

In the first half of that year of decision, 1776, George Wythe had helped to lead the colonies toward a proclamation of independence and to form the government of the new Commonwealth of Virginia. Then his state sent him back that autumn to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. That clearinghouse had the unenviable task of supervising the not perfectly united effort to win by arms the independence which had been so hopefully declared. In this relatively impotent and discordant assembly of diplomats or delegates from the thirteen states, as well as on the fields of battle, there were crucial conflicts, head-on collisions of opposite forces.

In November, 1776, a sectional cleavage arose in Congress because some of the New England states had offered to awards their new recruits for the Continental army a state bonus in addition to the uniform pay which Congress stipulated and was attempting to provide. This extra inducement to volunteers for military service embarrassed the representatives of other states which had not tried or could not afford to stimulate enlistments with equal generosity.2

To a newcomer in the Congress, William Ellery of Rhode Island, George Wythe addressed a humorous quatrain protesting this overzealousness of the New England states. With an allusion to one of the theological doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church, he drew a sharp contrast:

To works of supererogation

By others, some owe their salvation.

To what the good yankees are doing

Their duty beyond, we owe ruin.Ellery reciprocated this sprightly product of a congenial spirit which was still exuberant at the mature age of fifty. Wythe's infectious fun brought back to him a reply which twisted his rhymes to produce the opposite conclusion:

2 George Wythe to Thomas Jefferson, November 18, 1776, Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress; Samuel Adams to James Warren, November 9, 1776, Warren-Adams Letters, Being Chiefly a Correspondence among John Adams, Samuel Adams, and James Warren, I, 276, in Massachusetts Historical Society Collections, LXXII (1917); Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed. Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789 (Washington, 1904-1922), VI, 944.

Page 341

As by works supererogatory

Rom. Caths. are saved from purgatory,

So by what the Yankees good are doing

Buckskins will [be] saved from utter ruin.In another exchange of clever verses Ellery and Wythe put aside their dignity to take opposite sides of two other regional crosscurrents which divided the southern and northern states. New England delegates had helped to vote down in Congress Maryland's proposal that each soldier from that state should receive an immediate payment of ten dollars in lieu of an ultimate, postwar allotment of a hundred acres of western land.3 Also, the New Englanders had proposed that the three-fifths rule about the counting of slaves for purposes of per capita taxation should be revoked and that the whole Negro population should be considered in apportioning each state's share of the national expense. Ellery neatly chided George Wythe for having overindulgently taken Maryland's side on these issues:

Instead of controlling our Mary's cross humor,

You give what she asks you. Nay, you would do more.

First Virginia, instead of nobly persisting,

Gives up to Mary one roll for enlisting.

Mary then rising in her wild demands,

Virginia lays open the claims about lands.

Nay, more abounding in supererogation,

She, too, proposes the mode of taxation

To leave as it was before it was debated,

For perhaps by this might Mary be sated.

Pray, what is the cause of this indulgence so great,

Where discord and jarring subsisted of late?

I'll tell you, my friend, 'tis a truth very serious:

Interest will join states of sentiments various.Wythe's reply to this metrical accusation was a stout defense of the southern state's position and an appeal to justice and patriotism:

For farms in Utopia, the moon, or some fairyland

Compensations more worth were offered by Maryland.3 Samuel Adams to James Warren, November 9, 1776. Warren-Adams Letters, I, 276.

Page 342

In this it's denied our sister's cross humor'd,

Whatever by juntos or patriots be rumor'd.

Her brave men must fight, bleed, and suffer as others,

Leave orphans their dear babes and childless their mothers,

Give full many a fair Penelope heartaches,

Whilst their country of their virtuous earnings partakes

A very small pittance. Why this noise and stir then,

If, lest her shoulders bear too much of the burden,

She reject your unequal mode of taxation,

Demonstrate by numbers, without relaxation,

That ruin is doom'd her, and cries in distraction

She'll yield to the Old, not the New, English faction?

With candor attend to her effiagitation,

And these two demands grant without hesitation.

Virginia must feel for any neighbor oppress'd,

Cannot easy remain till the mischief's suppress'd;

And if slaves you include in your capitation,

Is equally injur'd, claims like defalcation.

E'en while, it is true, we're somewhat contrarient,

Yet interest will join those of sentiments variant.

And why not? For thence flows that blessing transcendent

All wish for devoutly, a state independent.

Then cease to object to a sister we're tender,

Indulgent with excess, unwilling to mend her,

If we favor petitions founded on reason,

With deference offer'd at convenient season.

Fell discord had too long among us existed.

From our councils cashier'd, if now reenlisted,

It with Tories will league to puzzle our measures

And spoil us of freedom, most precious of treasures.Ellery could find no better retort to Wythe's reply than to admit his defeat in three couplets which attempted to end their feigned literary rivalry. Humbly, in mock defeat, he closed with this one:

Let Wythe take the laurel his genius demands.

I ask but this boon: to be class'd with his friends.But the irrepressible poet in Wythe was unwilling to let so enjoyable

Page 343

an exchange of ironies be ended so suddenly. Prolong this swapping of meters he must! Since Congress's dull sessions were producing at the moment no new issues which lent themselves to similar versification, Wythe now drew upon his imagination and responded to Ellery's resignation from their poetic contest with this bright bit of nonsense:

With one epigram, though well hit off,

You must not expect, sir, to get off.

I can't for my life give o'er scribbling,

Except whilst I'm dreaming or quibbling.

If Howe, hither marching, friend Ell'ry,

Were near with his train of artill'ry

And bells in the city were chiming,

This strange cacoëthes of rhyming

Would not cease. Tell me not, in answer,

You can't write. It's known you well can, sir.Bestirring himself anew, Ellery revived his metrical correspondence by replying deferentially:

Unless you will take one line for your ten,

I never shall pay you, and indeed I shan't then.

The Muses will readily yield up their charms

To the poet that dreads not the thunder of arms.

They'll favor the brave, the youthful, the blithe,

Will fly from an Ellery and caress a Wythe.

Compelled thus to rhyme in my own defense,

I most humbly submit to your candor and sense.Now it was Wythe's turn modestly to feign defeat, so Ellery received next this mock confession that the Virginian had been vanquished:

You've not only quitted your arrear

But check'd my poetical career.

I flatter'd myself that Apollo

Had told me the Muses to follow.

But they—to Parnassus retiring

And frowning—forbade my aspiring,

Rejected my awkward addresses,

Bestow'd on my rival caresses,

Page 344

Made mirth of my passion for soaring,

And laugh'd at my anguish and roaring.

Whilst you mount with wing Pegasean

And, triumphing, sing Io Paean,

With eyes full of envy and surprise,

The laurel, I see, becomes your prize.Again it was the New Englander's turn to reiterate the superior talents of Wythe in the realm of the Muses:

The gen'rous idea your last piece expresses,

Instead of exciting my ardor, depresses.

The Muses, I know by experience, are gilts,

And he moves unsafely who moves upon stilts.

When my fancy was young, I ask'd of those lasses

To aid my ascent up the Mount of Parnassus.

They told me to follow, but as swift as the wind

They gain'd its high top and left me behind.

Thus jilted, I labor'd, but quickly I found

My tread was too clumsy for poetic ground.

And, wanting their aid to assist my weak passes,

I bid an adieu to the Mount of Parnassus.

Since that, contented with imitation,

Sometimes I've attempted an humble translation,

Inspir'd with an ardor deriv'd from gay Bacchus,

Of an eclogue of Mars or some ode of Flaccus.

Let Wythe take the laurels his genius demands.

I ask but this boon: to be class'd with his friends.So far as I know, this repeated plea ended the ridiculous, lyrical correspondence late in 1776—perhaps because Wythe had to return at the end of that year to Virginia to devote his talents to new assignments in the common cause. Eighteen months later, in a reminiscent, nostalgic letter to Samuel Adams, he asked, "Where is Ellery?" And he added, almost fretfully, "I have not had a couplet from him since I left Philadelphia." Then before he could even finish writing this letter the enjoyment which George Wythe found in trivial, amusing verses bubbled over again, so he enclosed something which he gave Adams permission to show to Ellery. Yet, shamefacedly, he commanded Adams not to let any-

Page 345

one learn "who so employs that time which he should spend better."4 Exactly what the enclosure was I have been unable to ascertain, but it may have been this translation of an epigram of the clever Roman poet, Martial, which I found in Wythe's hand among the poems with which he and Ellery had relieved the tedium of public service in 1776:

In all thy humors, whether grave or mellow,

Thou'rt such a touchy, testy fellow,

Hast so much mirth and wit and spleen about thee,

There is no living with thee or without thee.On second thought, were these poetic witticisms ridiculous? Or was not our nation blessed in possessing leaders who could bring to the heated battles of sectional strivings and the bitter jealousies of interstate rivalries the safety valve of a sense of humor?

4 George Wythe to Samuel Adams, August 1, 1778, Samuel Adams Papers, New York Public Library.

See also

References

- Jump up ↑ Poems on witty subjects in Congress (manuscript), by Ellery, William, 1727-1820; Wythe, George, 1726-1806; Boston Public Library, American Revolutionary War Manuscripts Collection.

- Jump up ↑ W. Edwin Hemphill, "George Wythe Courts the Muses: In Which, to the Astonishment of Everyone, That Silent, Selfless Pedant Is Found to Have Had a Sense of Humor," William and Mary Quarterly 3rd ser., 9, no. 3 (July 1952), 338-345.

- Jump up ↑ According to William DuVal, George Wythe's friend and executor, Wythe died on Sunday, June 8, 1806.

- Jump up ↑ The "Communication" quoted here was published on Tuesday, June 10, 1806, in both the Argus and the Richmond Enquirer.

External links

- American Revolutionary War Manuscripts at the Boston Public Library, Internet Archive.

- Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture.

- "Poems on Witty Subjects in Congress," American Revolutionary War Manuscripts Collection, Boston Public Library, Special Collections, MS.Ch.E.8.31-33.

- Read these poems in the Internet Archive.