Brent v. Porter

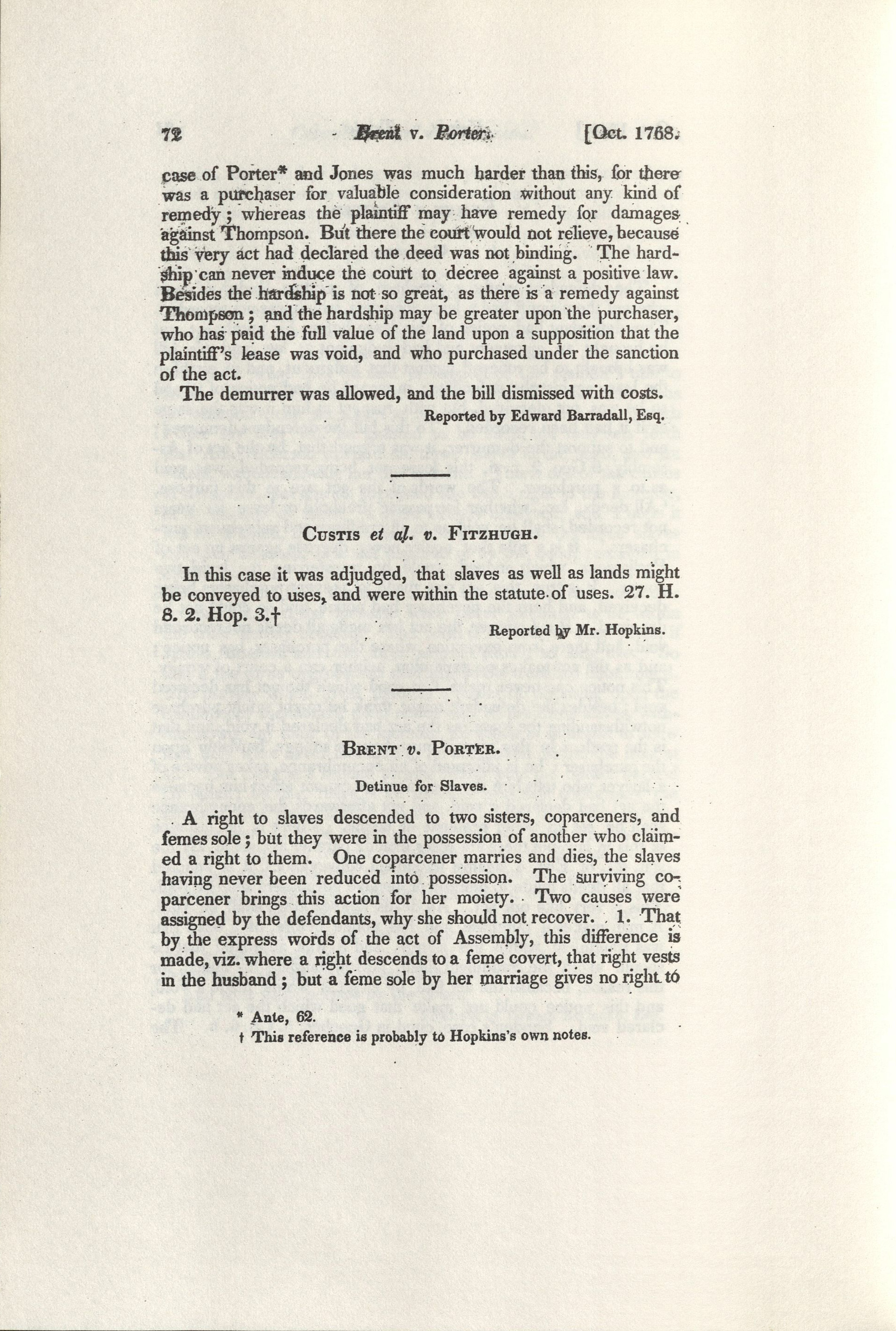

Brent v. Porter, Jefferson 72 (1768),[1] was a dispute over the detinue (a legal claim to recover wrongfully detained goods or possessions) of certain enslaved people between one sister and the widowed husband of the other sister.

Background

The dispute centers on two sisters who had a co-right of ownership to these enslaved people, but one sister dies before the enslaved persons ever entered her possession. The surviving sister brought this claim against the deceased sister’s husband alleging that she should recover her deceased sister’s ownership interest in the enslaved people.

The defendants offered two causes for why the plaintiff should not recover: (1) The express words of the Assembly vested a woman’s right in her husband; (2) That the husband should have been a part of the action for the enslaved along with the surviving sister. The court found for the plaintiff. On the issue of whether the husband had to any duty to the plaintiff, Edmund Pendleton argued that the husband could recover, whether possession occurred or not and if he took administration to recover the deceased wife’s right, he would be accountable to no one as he would be next of kin.

George Wythe argued that Pendleton was referring to the second statute of distribution, which was not at play here. Instead, if the husband were to recover the enslaved people, he would be accountable to the surviving sister as next of kin, under the first act of distribution. Meaning, that the because the deceased sister was not yet in possession of her right, the husband could participate in the claims to vest that right, but once gained possession he would be accountable to the surviving sister as next of kin.

The Court's Decision

Jefferson notes that the court adjudged for the plaintiffs, but he was not clear on what basis they made this decision. He does say that when the law entitled women to slaves whom she did not yet possess, the right survives to the husband, but if the woman survives the right should be hers. The purpose of the law was intended only to give the husband such a right as he would have had to the wife’s chattels, which is to reduce them into possession.

See also

References

- Jump up ↑ Thomas Jefferson, Reports of cases determined in the General Court of Virginia, from 1730 to 1740 and from 1768 to 1772, ed. Thomas Jefferson Randolph. (Charlottesville: F Carr and Co., 1829; Buffalo, N.Y. : W.S. Hein, 1981): 72.