A Law Dictionary, or, The Interpreter of Words and Terms

by John Cowell

| Cowell's Interpreter | |

|

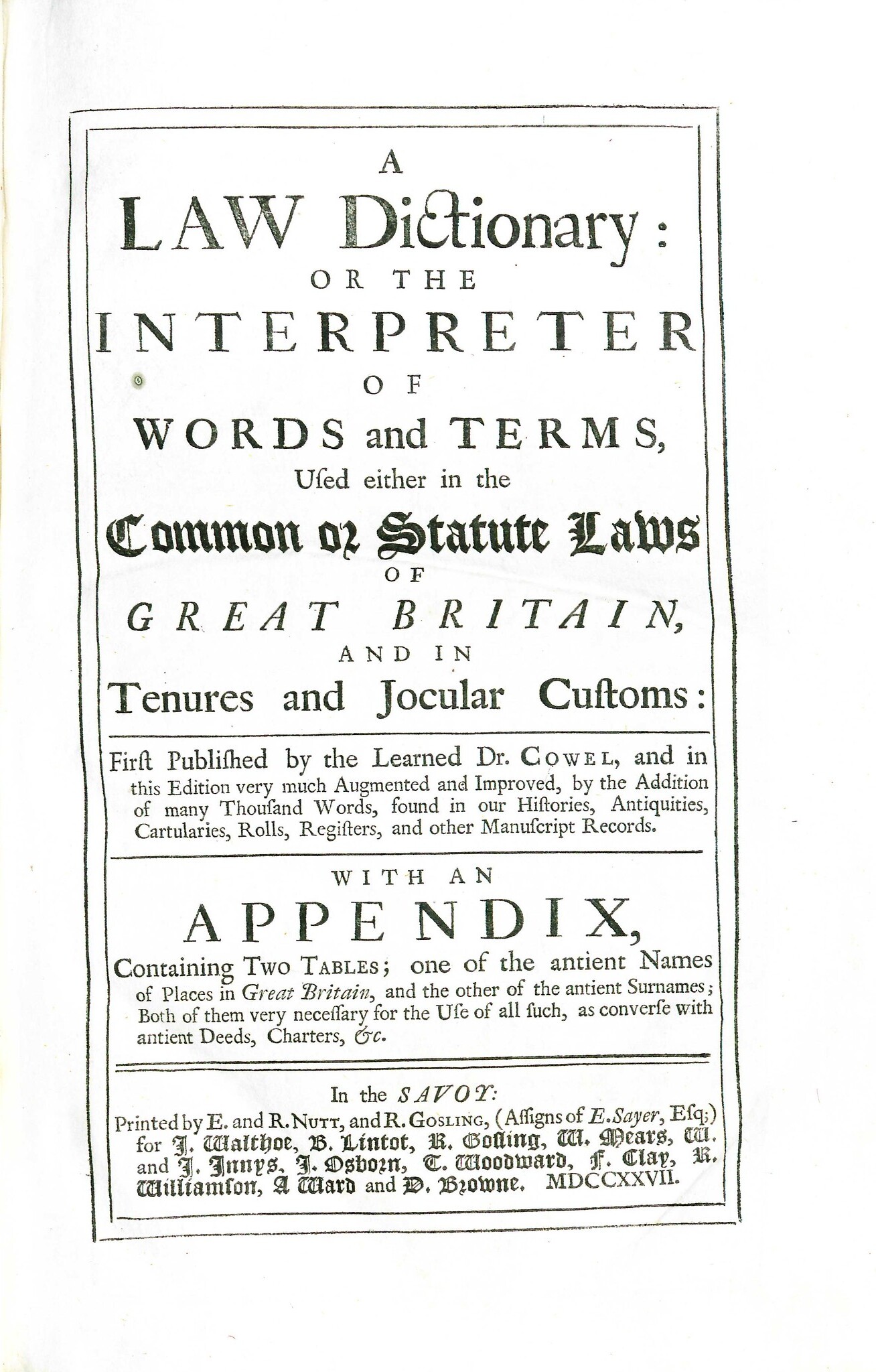

Title page from Cowell's Interpreter, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | John Cowell |

| Published | In the Savoy: Printed by E. and R. Nutt, and R. Gosling (assigns of E. Sayer, Esq.) for J. Walthoe, [etc.], 1727. |

| Date | 1727 |

| Language | English |

| Pages | 488 p. |

| Desc. | Folio (33 cm.) |

| Location | Shelf K-5 |

Born in Devon, John Cowell (1554–1611) studied at Eton College before attending King's College, Cambridge. He earned a B.A. (1575), an M.A. (1578) and an LLD in civil law (1584).[1] Elected Regius Professor of Civil Law at Cambridge in 1594, he also served as Vice-Chancellor from 1603 to 1604. He supplemented his academic roles with ecclesiastical positions under the archdeacon of Colchester and the archbishop of Canterbury.

Cowell published two academic works in his lifetime. In the first, Institutiones Juris Anglicani (1605), he attempted to explain common law to civil lawyers and instruct common law practitioners about the methods and principles of civil law.[2] His purpose in creating the book was to lay a groundwork for uniting English law and Scots law following the accession of James VI and I.[3] Not a particularly commercial achievement,[4] Institutiones Juris Anglicani did receive enough Parliamentary approbation during the Commonwealth for the order of an English translation.[5]

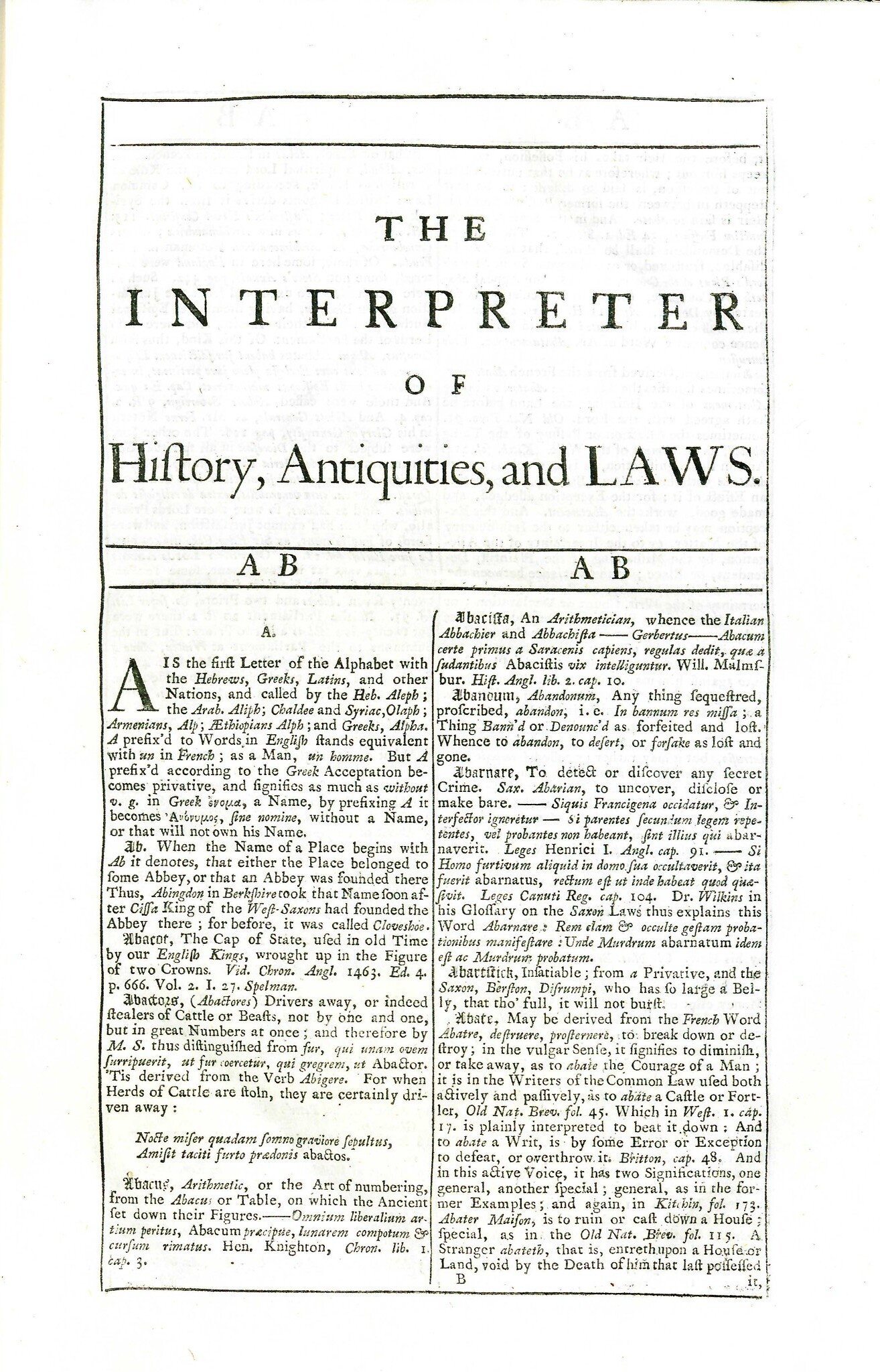

Cowell released his second publication The Interpreter, a comprehensive dictionary of English legal terms, in 1607.[6] Two years after the dictionary appeared, Cowell found himself embroiled in political controversy based on the definition of a few terms relating to the absolute power of kings and their relationship to parliament.[7] As one author explained, "[T]he scholarly lexicographer had become a pawn in the fierce political struggles between the king and the court on one side and the Commons and the common lawyers on the other..."[8] The specific definitions in question involved "Subsidy," "King," "Parliament" and "Prerogative."[9] After parliamentary debate in the Commons, sub-committee investigation, referral to the House of Lords and an interview of the author by the king himself, James I suppressed the book by royal prerogative.[10]

The motives for the entire episode were complex. In part, common lawyers objected to the intrusion into their sphere of a "professional civilian" or scholar in civil law.[11] A second reason involved embarrassing the king during negotiations regarding his revenues and debts.[12] Both Parliament and James I used the controversy to score points against each other, leaving Cowell caught between the two sides.[13] After some, probably short, term of imprisonment, Cowell resigned his position at Cambridge and died the following year.[14]

Remarkably, The Interpreter itself proved to be a valuable resource and survived the controversy, enjoying multiple reprintings. The second edition, with offending terms intact, was published in 1737. Subsequent editions, with those offending terms removed, appeared in 1658, 1672, 1684, 1701, 1708 and 1727 until the publication of Giles Jacob's New Law-Dictionary in 1729 effectively replaced Cowell's work.[15]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Quoted by George Wythe in his second argument for the plaintiff in Bolling v. Bolling:

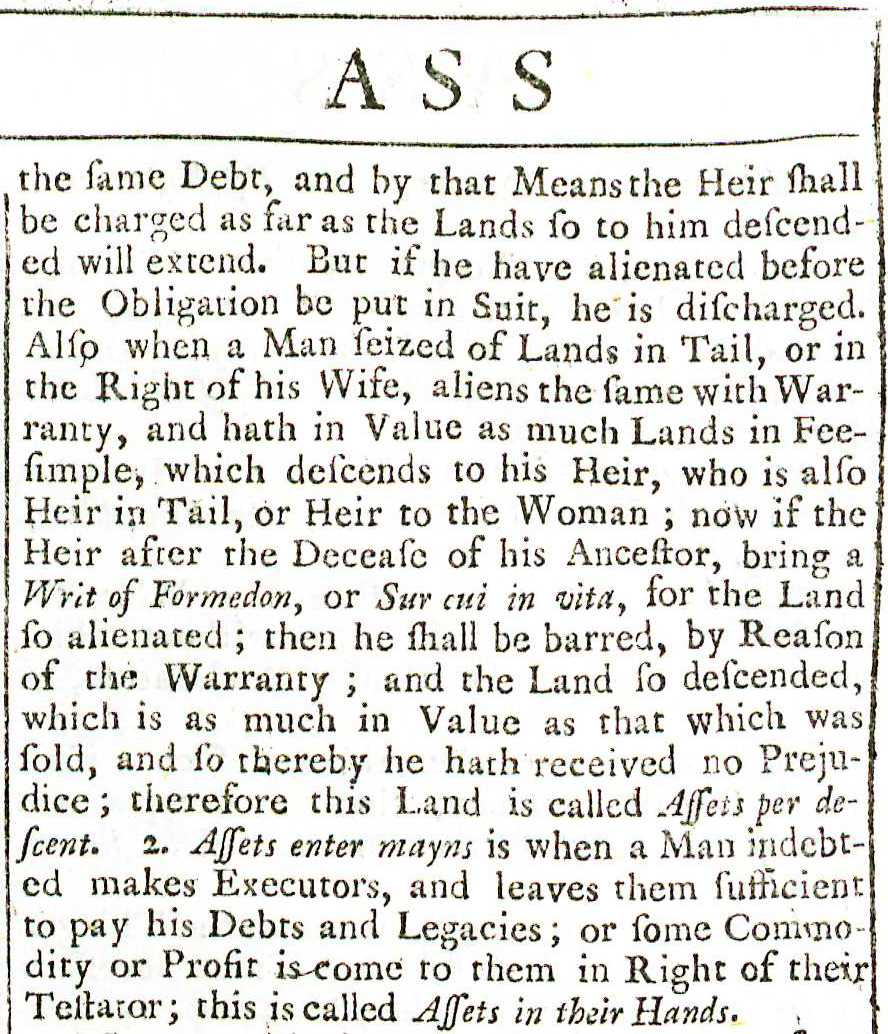

Assets enter mains is when a man indebted makes executors, and leaves them sufficient to pay his debts and legacies, or some commodity or profit is come to them in right of their testator this is called asses in their hands. Cow. interp. Assets[16]

The Brown Bibliography[17] lists the 1672 edition, Nomothetes: The Interpreter, based on Thomas Jefferson's copy at the Library of Congress. Dean's Memo[18] includes the 1727 edition in the section devoted to books "representative of [Wythe's] time." Comparison of the two editions to the quotation in Bolling v. Bolling suggests that the 1727 edition may be correct as it includes the phrase "his debts and legacies" while the 1672 edition does not. The Wolf Law Library followed Dean's suggestion and purchased a copy of the 1727 edition.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in modern quarter calf with gilt rule compartments on spine and gilt label on red morocco leather.

Images of the library's copy of this book are available on Flickr. View the record for this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

See also

References

- ↑ Brian P. Levack, ‘Cowell, John (1554–1611)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008, accessed 5 June 2023. All general biographical information taken from this source unless otherwise noted.

- ↑ S. B. Chrimes, "The Constitutional Ideas of Dr. John Cowell," in The English Historical Review, 64, no.253 (Oct. 1949): 463.

- ↑ ‘Cowell, John (1554–1611)’.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Crimes, "The Constitutional Ideas of Dr. John Cowell," 463.

- ↑ ‘Cowell, John (1554–1611)’.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Chrimes, "The Constitutional Ideas of Dr. John Cowell", 464.

- ↑ Ibid, 470.

- ↑ Ibid, 472.

- ↑ Ibid, 462.

- ↑ Ibid, 466-467.

- ↑ Ibid, 465.

- ↑ Ibid, 474.

- ↑ Ibid, 474-475.

- ↑ George Wythe, "Second Argument for Plaintiff," reprinted in Bernard Schwartz, Barbara Wilcie Kern, R. B. Bernstein, eds., Thomas Jefferson and Bolling v. Bolling: Law and the Legal Profession in Pres-Revolutionary America (San Marino, CA: The Huntington Library; New York: New York University School of Law, 1997), 311-312.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433.

- ↑ Memorandum from Barbara C. Dean, Colonial Williamsburg Found., to Mrs. Stiverson, Colonial Williamsburg Found. (June 16, 1975), 14 (on file at Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary).