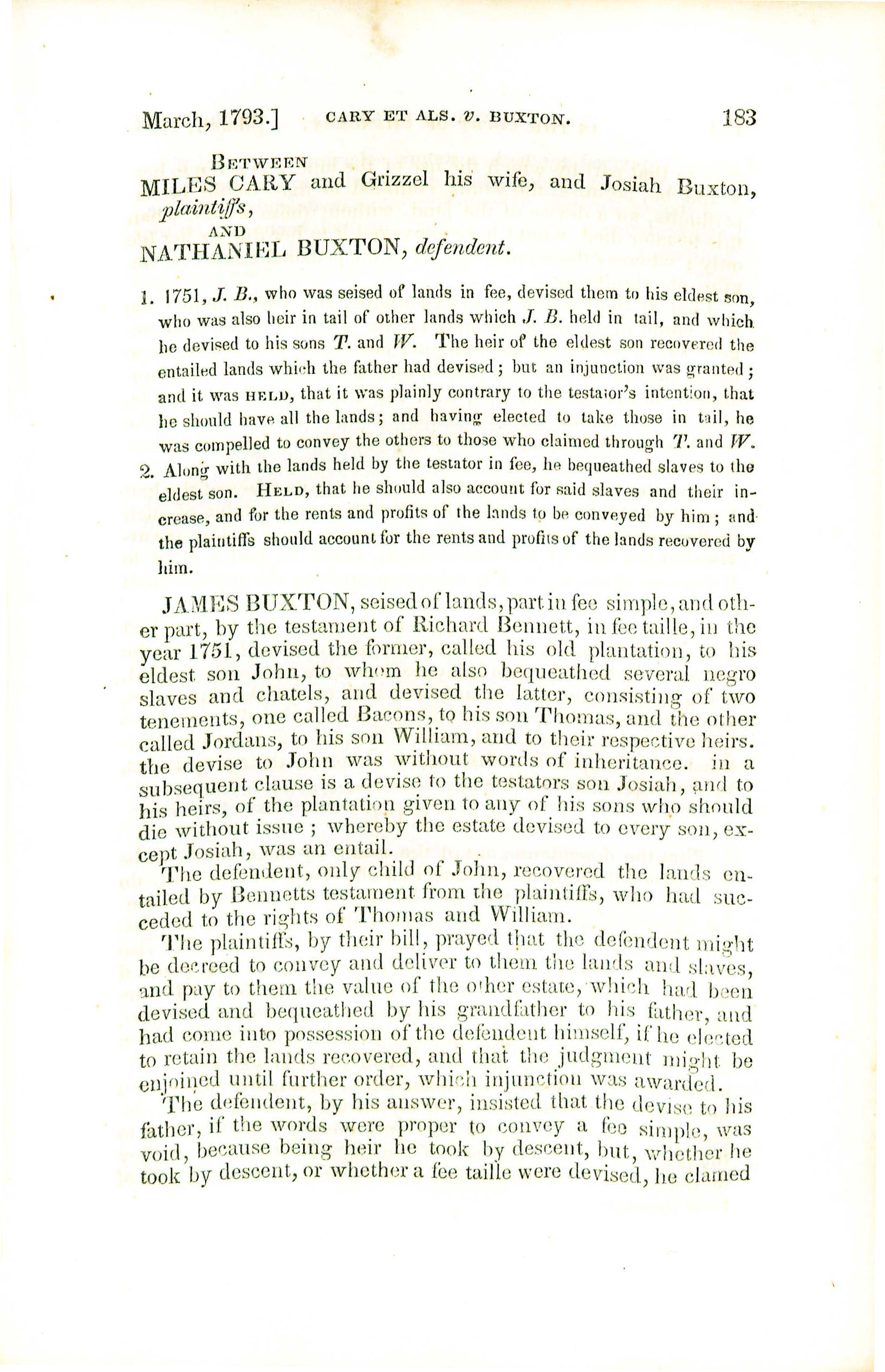

Cary v. Buxton

Cary v. Buxton, Wythe 183 (1793),[1] involved a dispute over distributing an inheritance. In his decision, Wythe refers to several contemporary and classical sources for examples of amending or voiding a will to match the deceased's inferred intent.

Background

James Buxton owned land called "Old Plantation" in fee simple.[2] In his will and testament, he gave Old Plantation to his eldest son John, along with several slaves.

James also owned two other properties, called Bacons and Jordans, that he inherited from Richard Bennett in fee tail.[3] A later clause in James's will awarded Bacons to his son Thomas and Thomas's heirs, and gave Jordans to James's son William and William's heirs.

Another clause in James's will said that all the property he gave his sons, except for Josiah, was in fee tail. The will said that Josiah and Josiah's heirs would get the parts of the plantation that were given to any of James's sons who died without an heir.

Nathaniel Buxton, the defendant, was John's only child.

Miles Cary and his wife Grizzel[4] were the plaintiffs, along with Josiah. The Carys and Josiah inherited Thomas's and William's land rights.

Nathaniel had inherited Old Plantation and the slaves who went with it from John, and had recovered Bacons and Jordans from the Carys and Josiah.[5] The plaintiffs filed a bill with the High Court of Chancery saying that if Nathaniel wanted to keep Bacon and Jordans, the plaintiffs wanted the Chancery Court to force Nathaniel to give them Old Plantation and the slaves whom James left to John, and compensate them for the value of Bacons and Jordans.

Nathaniel answered that he had inherited Old Plantation by descent, making any language in James's will about inheriting by fee tail void. Nathaniel said he had the rights to Old Plantation, Bacons, and Jordans, regardless of whether by descent or in fee tail, but if he could only pick between the two gifts, he wanted to keep Bacons and Jordans. Nathaniel said that some of the slaves John inherited from James were dead, Nathaniel had sold one, and the rest escaped to the British during the Revolution.

The Court's Decision

On March 2, 1793, the High Court of Chancery ordered Nathaniel to turn over Bacons and Jordans to the Carys and to Josiah. Wythe said that there is a presumption that James wanted the inheritance split among his heirs. Had James known that John's heirs would eventually also get hold of the inheritance James left for Thomas and William, Wythe argued, James would have found some way for Thomas's and William's heirs to be compensated from John's inheritance. Wythe amended James Buxton's testament so that Thomas and William and their heirs inherited "Old Plantation" in fee simple.

Wythe cited several examples from contemporary and classical sources of situations in which similar amendments to testaments were made to conform to the deceased's presumed wishes, and situations in which testaments were completely voided if they were found contrary to the deceased's presumed wishes. Among the sources Wythe referred to were the Digest of Justinian and the Institutes of Justinian, Quintilian, Cicero's oratories, Gilbert's Reports of Cases in Equity, Valerius Maximus, and Lord Home's Principles of Equity.

The Chancery Court ordered Nathaniel to turn over one half of Old Plantation to the Carys, and the other half to Josiah. The Court also ordered Nathaniel to turn over the remaining slaves from the inheritance to the plaintiffs, and to account for the slaves John had inherited as well as the rents and profits since December 31, 1770, from Old Plantation, Bacons, and Jordans.

Works Cited or Referenced by Wythe

Justinian's Digest

Quotes in Wythe's opinion:

Si ita scriptum sit: si filius mihi natus fuerit, ex besse heres esto: ex reliqua parte uxor mea heres esto. si vero filia mihi nata fuerit, ex triente heres esto: ex reliqua parte uxor heres esto, et filius et filia nati essent, dicendum est assem distribuendum esse in septem partes, ut ex his filius quattuor, uxor duas, filia unam partem habeat: ita enim secundum voluntatem testantis filius altero tanto amplius habebit quam uxor, item uxor altero tanto amplius quam filia: licet enim suptili iuris regulae conveniebat ruptum fieri testamentum, attamen cum ex utroque nato testator voluerit uxorem aliquid habere, ideo ad huiusmodi sententiam humanitate suggerente decursum est, quod etiam Juventio Celso apertissime placuit. Dig. lib. XXVIII. tit. II. 1. 13. Translation: If someone has written thus: ‘If a son should be born to me, he will be heir of two-thirds [of my estate]: my wife will be the heir of the left-over portion. But if a daughter is born to me, she will be heir of one-third: my wife will be the heir of the left-over portion.’ If both a son and daughter are born, it must be stated that the whole is to be divided into seven parts, so that from these, the son shall have four, the wife two and the daughter one; for in this way, according to the wishes of the testator, the son will have two times more than the wife, likewise the wife will have two time more than the daughter; for although by the literal rule of the law, it could be held that the will was made broken, nevertheless, because the testator wanted his wife to have something no matter which child was born, therefore, with human decency suggesting towards this opinion, it is decided, that which was also clearly pleasing to Juventius Celsus.[6]

Clemens Patronus testamento caverat, ut, si sibi filius natus fuisset, heres esset, si duo filii, ex aequis partibus heredes heres essent, si duae filiae, similiter: si filius et filia, filio duas partes, filiae tertiam dederat. duobus filiis et filia natis quaerebatur, quemadmodum in proposita specie partes faciemus, cum filii debeant pares esse vel etiam singuli duplo plus quam soror accipere? quinque igitur partes fieri oportet, ut ex his binas masculi, unam foemina accipiat. Dig. lib. XXVIII tit. V. 1. 81. Translation: Clemens Patronus stipulated in his will, that, if a son should be born to him, he would be his heir; if he had two sons, they would be heirs of equal portions of the estate; likewise, if he has two daughters. If he has a son and daughter, he bestowed two thirds to the son and one to the daughter. With two sons and a daughter having been born it was asked how we should make divisions in the proposed case, since the sons’ [parts] ought to be equal and also twice more than what their sister receives. Therefore, it is proper that five portions be made, so that from these, the sons receive two and the daughter one.[7]

Pactumeius Androsthenes Pactumeiam Magnam filiam Pactumeii Magni ex asse heredem instituerat, eique patrem eius substituerat. Pactumeio Magno occiso et rumore perlato, quasi filia quoque eius mortua, mutavit testamentum Noviumque Rufum heredem instituit hac praefatione: quia heredes, quos volui habere mihi contingere non potui, Novius Rufus heres esto. pactumeia magna supplicavit imperatores nostros et cognitione suscepta, licet modus institutioni contineretur, quia falsus non solet obesse, tamen ex voluntate testantis putavit imperator ei subveniendum. igitur pronuntiavit hereditatem ad magnam pertinere, sed legata ex posteriore testamento eam praestare debere, proinde atque si in posterioribus tabulis ipsa fuisset heres scripta. Dig. lib. XXVIII. tit. V. 1. 92. Translation: Pactumeius Androsthenes established Pactumeia Magna daughter of Pactumeius Magnus, heir of his whole estate and substituted her father for her. With Pactumeius Magnus killed and the rumor being spread, as if his daughter was also dead, he changed his will and appointed Novius Rufus heir with this preface: "because I am unable to grant for myself the heirs, whom I wished to have, Novius Rufus shall be my heir." Pactumeia Magna petitioned our emperors and with an inquiry having been undertaken, it is permitted that the manner be contained for instruction, because such false things are not accustomed to being a nuisance, nonetheless the emperor thought according the wishes of the testator he ought to come to her aid. Therefore, he pronounced that the inheritance belonged to Magna, but she ought to make good the legacy from the latter will, in the same manner as if she herself was the heir written on the latter document.[8]

[T]estamentum aut non iure factum dicitur, ubi sollemnia iuris defuerunt: aut nullius esse momenti, cum filius qui fuit in patris potestate praeteritus est.T]estamentum aut non iure factum dicitur, ubi sollemnia iuris defuerunt: aut nullius esse momenti, cum filius qui fuit in patris potestate praeteritus est. Dig. lib. XXVIII. tit. III. 1. 1. Translation: Either a will is not called executed according to the law, when the formalities of the law were neglected: or to be of no importance, when a son who was in the power of his father is passed over.[9]

For these quotes, Wythe most likely used his copy of the Corpus Juris Civilis which includes the Digest of Justinian.

Justinian's Institutes

Quotation in Wythe's opinion:

Testamentum dicitur nullius esse momenti, cum filius, qui fuit in patris potestate, praeteritus est. Dig. lib. XXVIII. tit. III. 1. 1. Translation: At that time, the will is of no importance, when the son, who was under his father’s power, is disinherited.[10]

Cicero's On the Orator

Quotes in Wythe's opinion:

De militis morte, cum domum falsus ab exercitu nuntius venisset, et pater ejus, re credita, testamentum mutasset, et quem ei visum esset, fecisset heredem, essetque ipse mortuus: res delta est ad centumviros, cum miles domnum revenisseit, egissetque lege in herefitatem paternam. nempe in ea causa quaesitum est de jure civili, possetne paternorum bonorum exheres esse filius, quem pater testa mento neque heredem, neque exheredem, scripsset nominatum? Cicero de oratore, lib. 1. c. 38. Translation: The soldier, of whose death a false report having been brought home from the army, and his father, through giving credit to that report, having altered his will, and appointed another person, whom he thought proper, to be his heir, and having then died himself, the affair, when the soldier returned home, and instituted a suit for his paternal inheritance, came on to be heard before the centumviri? The point assuredly in that case was a question of civil law, whether a son could be disinherited of his father’s possessions, whom the father neither appointed his heir by will, nor disinherited by name?[11]

Num quis eo testamento, quod paterfamilias ante fecit quam ei filius natus est, hereditatem petit? nemo: quia constat, agnascendo rumpi testmentum: ergo in hoc genere juris judicia nulla sunt. Cicero de oratore, lib. 1. c. 57. Translation: Surely no one would seek an inheritance from a will which the paterfamilias made before a son was born to him? No one would: because it is agreed, by the birth, the will is broken. Therefore in this type of law, there are no legal actions.[12]

Quintilian's Institutes of Oratory

Quotation in Wythe's opinion:

Curius substitutus heres erat, si posthumus ante tutelae suae annos decessisset. non est natus. propinqui bona sibi vendicabant. quis dubitaret, quin ea voluntas fuisset testantis. ut is non nato filio heres esset, qui mortuo? sed hoc non scripserat. Quinctil. de institut. orator. lib. VII. c. VI. Translation: (Wythe has added the name “Curius” at the beginning of this quote.) Curius was made an alternative heir, if a posthumous son died before the years of his tutelage. No such son was born, and a relative was selling the goods for himself. Who could doubt that it was the will of the testator, that with no son being born, the heir would be the same person who would be heir with the son being dead? But he had not written this.[13]

Valerius Maximus's Nine Books of Memorable Deeds and Sayings

Quotation in Wythe's opinion:

Valerius Maximus, lib. 7. c.7, reports that adolscens, omnibus, non solum consiliis sed etiam, sententis superior decessit. Translation: This passage refers to the case of a young man, who was falsely reported dead in war, so that his father omitted him from his will. As a consequence, the son has to argue for recognition of his heritage (and is successful).[14]

References

- ↑ George Wythe, Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery with Remarks upon Decrees by the Court of Appeals, Reversing Some of Those Decisions, 2nd ed., ed. B.B. Minor (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1852), 183.

- ↑ Fee simple was the broadest property interest the law allowed. An owner in fee simple could transfer ownership to anyone he chose. If the owner died without leaving a will, the property in fee simple would go to the closest heir.

- ↑ Ownership in fee tail can only be inherited by specific descendants, and ends when its current owner dies without qualifying heirs.

- ↑ Wythe did not explicity state the Carys' relationship to the Buxtons, but the best guess from reading the case is that Grizzel was either Thomas's or William's daughter.

- ↑ Wythe did not explain exactly how Nathaniel got the land from the plaintiffs, but from Wythe's statement that Nathaniel got Bacons and Jordans "by the testament of Richard Bennett", the most logical inference is that when Thomas and William died, Nathaniel convinced a court that the plaintiffs were not heirs eligible to receive the property in fee tail. If a court found that the plaintiffs were not eligible to receive Bacons and Jordans in fee tail, then either Nathaniel convinced the court that he was an eligible heir in fee tail, or that he would inherit the property by right of descent.

- ↑ Wythe, Decisions of Cases, 184-85.

- ↑ Ibid., 185.

- ↑ Ibid., 186.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 186.

- ↑ Ibid., 185. Translation: J.S. Watson

- ↑ Ibid., 186.

- ↑ Ibid., 184.

- ↑ Ibid., 186.