Difference between revisions of "Works of Virgil, Containing His Pastorals, Georgics and Æneis"

(Summary paragraphs by Michael Wyatt & Evidence.) |

|||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

===by Virgil=== | ===by Virgil=== | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

| − | + | {{BookPageInfoBox | |

| − | Virgil (Publius Vergilius Maro) 70 BCE–19BCE | + | |imagename=VirgilWorks1748v1.jpg |

| + | |link=https://catalog.swem.wm.edu/law/Record/3474034 | ||

| + | |shorttitle=The Works of Virgil | ||

| + | |vol=volume one | ||

| + | |author=Virgil | ||

| + | |trans=John Dryden | ||

| + | |publoc=London | ||

| + | |publisher=Printed by J. and R. Tonson and S. Draper | ||

| + | |year=1748 | ||

| + | |edition=Seventh | ||

| + | |lang=English | ||

| + | |set=3 | ||

| + | |desc=17 cm. | ||

| + | }}Virgil (Publius Vergilius Maro) 70 BCE–19BCE | ||

This volume contains the three most important of Virgil’s works: the ''Pastorals'' (“Bucolics” or “Eclogues”), the ''Georgics'', and the ''Aeneid''. The ''Pastorals'' muse on the idyllic life of shepherds in northern Italy, and they range in quality from apt imitations of Greek poems to keen literary and societal prognostication.<ref>Virgil, ''Georgics'', trans. Peter Fallon, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), xiv.</ref> The ''Georgics'' are, similarly, meditations on the nature of agriculture. The name “Georgics” refers to the Greek phrase for “working the land” and the word for “farmer.”<ref>Ibid.</ref> Where Virgil’s pastoral poems were largely imitative, the focus and depth of his Georgics were unprecedented.<ref>Ibid, xiii.</ref> Finally, the ''Aeneid'' is Virgil’s great epic, following the tradition of Homer.<ref>Virgil, ''Aeneid'', ed. Clyde Pharr, (Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci, 2007), 1–4.</ref> The work follows the story of Aeneis, who leaves behind his conquered homeland of Troy and goes on to found the culture that will eventually become Rome. Virgil himself captured the scope of these three works with the inscription on his tombstone, “cecini pascua rura duces” (I sang of farms, fields, and heroes).<ref>Ibid.</ref> | This volume contains the three most important of Virgil’s works: the ''Pastorals'' (“Bucolics” or “Eclogues”), the ''Georgics'', and the ''Aeneid''. The ''Pastorals'' muse on the idyllic life of shepherds in northern Italy, and they range in quality from apt imitations of Greek poems to keen literary and societal prognostication.<ref>Virgil, ''Georgics'', trans. Peter Fallon, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), xiv.</ref> The ''Georgics'' are, similarly, meditations on the nature of agriculture. The name “Georgics” refers to the Greek phrase for “working the land” and the word for “farmer.”<ref>Ibid.</ref> Where Virgil’s pastoral poems were largely imitative, the focus and depth of his Georgics were unprecedented.<ref>Ibid, xiii.</ref> Finally, the ''Aeneid'' is Virgil’s great epic, following the tradition of Homer.<ref>Virgil, ''Aeneid'', ed. Clyde Pharr, (Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci, 2007), 1–4.</ref> The work follows the story of Aeneis, who leaves behind his conquered homeland of Troy and goes on to found the culture that will eventually become Rome. Virgil himself captured the scope of these three works with the inscription on his tombstone, “cecini pascua rura duces” (I sang of farms, fields, and heroes).<ref>Ibid.</ref> | ||

John Dryden’s translation of the ''Georgics'' led to a surge in their popularity among English speakers in the eighteenth century, inspiring many romantic ideas about rural life and agriculture.<ref>L. P. Wilkinson, ''The Georgics of Virgil: A Critical Survey'', (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 299–304.</ref> | John Dryden’s translation of the ''Georgics'' led to a surge in their popularity among English speakers in the eighteenth century, inspiring many romantic ideas about rural life and agriculture.<ref>L. P. Wilkinson, ''The Georgics of Virgil: A Critical Survey'', (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 299–304.</ref> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

Revision as of 16:01, 28 January 2014

by Virgil

| The Works of Virgil | |

|

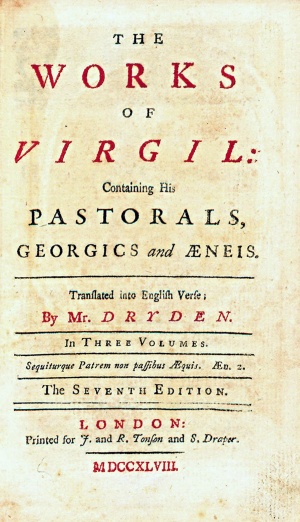

Title page from The Works of Virgil, volume one, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Virgil |

| Translator | John Dryden |

| Published | London: Printed by J. and R. Tonson and S. Draper |

| Date | 1748 |

| Edition | Seventh |

| Language | English |

| Volumes | 3 volume set |

| Desc. | 17 cm. |

Virgil (Publius Vergilius Maro) 70 BCE–19BCE

This volume contains the three most important of Virgil’s works: the Pastorals (“Bucolics” or “Eclogues”), the Georgics, and the Aeneid. The Pastorals muse on the idyllic life of shepherds in northern Italy, and they range in quality from apt imitations of Greek poems to keen literary and societal prognostication.[1] The Georgics are, similarly, meditations on the nature of agriculture. The name “Georgics” refers to the Greek phrase for “working the land” and the word for “farmer.”[2] Where Virgil’s pastoral poems were largely imitative, the focus and depth of his Georgics were unprecedented.[3] Finally, the Aeneid is Virgil’s great epic, following the tradition of Homer.[4] The work follows the story of Aeneis, who leaves behind his conquered homeland of Troy and goes on to found the culture that will eventually become Rome. Virgil himself captured the scope of these three works with the inscription on his tombstone, “cecini pascua rura duces” (I sang of farms, fields, and heroes).[5]

John Dryden’s translation of the Georgics led to a surge in their popularity among English speakers in the eighteenth century, inspiring many romantic ideas about rural life and agriculture.[6]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Thomas Jefferson listed Dryden's Virgil. 3.v. 12mo. in his inventory of Wythe's Library in the section of titles he kept for himself. Brown's Bibliography[7] includes the 1748 edition published in London based on the copy Jefferson sold to the Library of Congress.[8] This volume does not survive. George Wythe's Library[9] on LibraryThing indicates "Precise edition unknown. Several three-volume editions were published at London, the first in 1721."

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in full gilt ruled Calfskin. Gilt ruled spine compartments with elaborate gilt tooled motifs. Gilt tooled raised bands with morocco labels. Illustrated throughout by full page copper plate engravings. Purchased from Heldfond Book Gallery, Ltd.

View this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

References

- ↑ Virgil, Georgics, trans. Peter Fallon, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), xiv.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid, xiii.

- ↑ Virgil, Aeneid, ed. Clyde Pharr, (Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci, 2007), 1–4.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ L. P. Wilkinson, The Georgics of Virgil: A Critical Survey, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 299–304.

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

- ↑ E. Millicent Sowerby, Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, 2nd ed. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983), 4:421-422 [no.4282].

- ↑ LibraryThing, s. v. "Member: George Wythe," accessed on June 28, 2013, http://www.librarything.com/profile/GeorgeWythe