Difference between revisions of "Reports of Sir Henry Yelverton"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE: ''The Reports of Sir Henry Yelverton''}} | {{DISPLAYTITLE: ''The Reports of Sir Henry Yelverton''}} | ||

| + | <big>''The Reports of Sir Henry Yelverton ... of Divers Special Cases in the Court of King's Bench, as Well in the Latter Rnd of the Reign of Q. Elizabeth, as in the First Ten Years of K. James''</big> | ||

===by Sir Henry Yelverton=== | ===by Sir Henry Yelverton=== | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

| Line 6: | Line 7: | ||

|link=https://catalog.swem.wm.edu/law/Record/2855755 | |link=https://catalog.swem.wm.edu/law/Record/2855755 | ||

|shorttitle=The Reports of Sir Henry Yelverton | |shorttitle=The Reports of Sir Henry Yelverton | ||

| + | |commontitle=Yelverton's Reports | ||

|author=Sir Henry Yelverton | |author=Sir Henry Yelverton | ||

|publoc=London, In the Savoy | |publoc=London, In the Savoy | ||

|publisher=Printed by E. and R. Nutt, and R. Gosling (assigns of E. Sayer) for W. Feales | |publisher=Printed by E. and R. Nutt, and R. Gosling (assigns of E. Sayer) for W. Feales | ||

|year=1735 | |year=1735 | ||

| − | |edition=Third | + | |edition=Third, corrected |

|lang=Greek | |lang=Greek | ||

| − | | | + | |pages=7, 228, [23] |

|desc=Folio (32 cm.) | |desc=Folio (32 cm.) | ||

| − | }}Sir Henry Yelverton (1566-1630), judge and politician, was the eldest son of Sir Christopher | + | }}[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Yelverton_(attorney-general) Sir Henry Yelverton] (1566-1630), judge and politician, was the eldest son of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sir_Christopher_Yelverton Sir Christopher Yelverto], the noted judge and speaker of the House of Commons.<ref>S. R. Gardiner, rev. Louis A. Knafla, [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/30214?docPos=528317 “Yelverton, Sir Henry (b. 1566, d. 1630)”], ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed February 24, 2014.</ref> |

| − | According to one scholar, “genius, education, and public honor appear, indeed, to have been heirlooms in his family.”<ref>John William Wallace, | + | According to one scholar, “genius, education, and public honor appear, indeed, to have been heirlooms in his family.”<ref>John William Wallace, ''The Reporters, Arranged and Characterized with Incidental Remarks'', 4th ed., rev. and enl. (Boston: Soule and Bugbee, 1882), 212.</ref> In fact, Yelverton’s quick rise to prominence may be attributed to the public favor he received on account of his father’s good name.<ref>Ibid. 214</ref> In 1581, he matriculated from Christ’s, Cambridge and graduated BA from Peterhouse in 1584.<ref>"Yelverton, Sir Henry," ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography''.</ref> Yelverton’s puritan leanings were informed by his studies at Cambridge.<ref>Ibid.</ref> After gaining admittance to Gray’s Inn in 1580, he was called to bar in 1593.<ref>Ibid.</ref><br /> |

| − | + | <br /> | |

| − | + | His political activities began in 1597 when he was elected MP for Northhampton and sat on several committees.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Although not returned in 1601, he was in 1604 for the first parliament of James I.<ref>Ibid.</ref> In Parliament, he became known as an “independent man who spoke his mind.”<ref>Ibid.</ref> It was Yelverton’s outspokenness about the rights of parliament which tended to get him in trouble with the king, even though he supported the royal prerogative.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Despite his the troublesome independence of his views, Yelverton regained the trust of King James I by gaining audience and explaining his views.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Ultimately this reconciliation enabled him to serve the king in various capacities.<ref>Ibid.</ref> In 1613, Yelverton was made solicitor-general and knighted.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Ultimately, Yelverton became attorney general after the king appointed Sir Francis Bacon lord keeper.<ref>Ibid.</ref><br /> | |

| − | His political activities began in 1597 when he was elected MP for Northhampton and sat on several committees. <ref>Ibid.</ref> | + | <br /> |

| − | + | Despite his advancement to these positions of power, his puritan independence once again got him in trouble.<ref>Ibid.</ref> The Duke of Buckingham, with whom Yelverton had an adversarial relationship, accused him of abusing his position as commissioner of patents.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Their animosity came to a head when Yelverton accused Buckingham of standing “still att the Kinges elbowe ready to hew me down.”<ref>Ibid.</ref> Because of these words, Yelverton was found guilty of slandering Buckingham in addition to the underlying crime of impugning the king through his actions as commissioner of patents.<ref>Ibid.</ref> In 1621, Yelverton returned to the king’s bench, chancery, Star Chamber, and assize circuits.<ref>Ibid.</ref> In 1625 he was made serjeant-at-law and became judge of the court of common pleas, five years before he died.<ref>Ibid.</ref><br /> | |

| − | + | <br /> | |

| − | Despite his advancement to these positions of power, his puritan independence once again got him in trouble.<ref>Ibid.</ref> The Duke of Buckingham, with whom Yelverton had an adversarial relationship, accused him of abusing his position as commissioner of patents.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Their animosity came to a head when Yelverton accused Buckingham of standing “still att the Kinges elbowe ready to hew me down.”<ref>Ibid.</ref> Because of these words, Yelverton was found guilty of slandering Buckingham in addition to the underlying crime of impugning the king through his actions as commissioner of patents.<ref>Ibid.</ref> | + | Scholars hold Yelverton’s ''Reports'' in high regard. Although they were never intended for publication, they are considered “among the best of the older books both for value of decision and essential accuracy of report.” <ref>Wallace, ''The Reporters'', 211.</ref> |

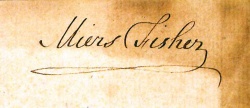

| − | + | [[File:YelvertonReportsofSirHenryYelverton1735Inscription.jpg|left|thumb|250px|<center>Previous owner's signature, front flyleaf.</center>]] | |

| − | |||

| − | Scholars hold Yelverton’s | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ==Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library== | ||

| − | Both [[Dean Bibliography|Dean's Memo]]<ref>[[Dean Bibliography|Memorandum from Barbara C. Dean]], Colonial Williamsburg Found., to Mrs. Stiverson, Colonial Williamsburg Found. (June 16, 1975), 15 (on file at Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary).</ref> and the [https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433 Brown Bibliography]<ref> Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433</ref> suggest Wythe owned | + | Both [[Dean Bibliography|Dean's Memo]]<ref>[[Dean Bibliography|Memorandum from Barbara C. Dean]], Colonial Williamsburg Found., to Mrs. Stiverson, Colonial Williamsburg Found. (June 16, 1975), 15 (on file at Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary).</ref> and the [https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433 Brown Bibliography]<ref> Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433</ref> suggest Wythe owned the third (1735) edition of Yelverton's ''Reports'' based on notes in John Marshall's commonplace book.<ref>''The Papers of John Marshall,'' eds. Herbert A. Johnson, Charles T. Cullen, and Nancy G. Harris (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, in association with the Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1974), 1:45.</ref> The Wolf Law Library purchased a copy of the same edition. |

==Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy== | ==Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy== | ||

| − | Bound in recent period-style quarter calf over marbled boards with renewed endpapers. | + | Bound in recent period-style quarter calf over marbled boards with renewed endpapers. Includes early owner signature of "Miers Fischer" the front flyleaf and title page. Purchased from The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. |

View this book in [https://catalog.swem.wm.edu/law/Record/2855755 William & Mary's online catalog.] | View this book in [https://catalog.swem.wm.edu/law/Record/2855755 William & Mary's online catalog.] | ||

| Line 39: | Line 37: | ||

==External Links== | ==External Links== | ||

| − | [http://books.google.com/books?id=E-oDAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover Google Books] | + | Read this book in [http://books.google.com/books?id=E-oDAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover Google Books.] |

[[Category:Case Reports]] | [[Category:Case Reports]] | ||

Revision as of 14:14, 4 March 2014

The Reports of Sir Henry Yelverton ... of Divers Special Cases in the Court of King's Bench, as Well in the Latter Rnd of the Reign of Q. Elizabeth, as in the First Ten Years of K. James

by Sir Henry Yelverton

| Yelverton's Reports | |

|

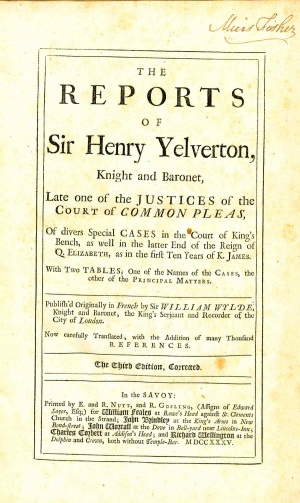

Title page from The Reports of Sir Henry Yelverton, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Sir Henry Yelverton |

| Published | London, In the Savoy: Printed by E. and R. Nutt, and R. Gosling (assigns of E. Sayer) for W. Feales |

| Date | 1735 |

| Edition | Third, corrected |

| Language | Greek |

| Pages | 7, 228, [23] |

| Desc. | Folio (32 cm.) |

Sir Henry Yelverton (1566-1630), judge and politician, was the eldest son of Sir Christopher Yelverto, the noted judge and speaker of the House of Commons.[1]

According to one scholar, “genius, education, and public honor appear, indeed, to have been heirlooms in his family.”[2] In fact, Yelverton’s quick rise to prominence may be attributed to the public favor he received on account of his father’s good name.[3] In 1581, he matriculated from Christ’s, Cambridge and graduated BA from Peterhouse in 1584.[4] Yelverton’s puritan leanings were informed by his studies at Cambridge.[5] After gaining admittance to Gray’s Inn in 1580, he was called to bar in 1593.[6]

His political activities began in 1597 when he was elected MP for Northhampton and sat on several committees.[7] Although not returned in 1601, he was in 1604 for the first parliament of James I.[8] In Parliament, he became known as an “independent man who spoke his mind.”[9] It was Yelverton’s outspokenness about the rights of parliament which tended to get him in trouble with the king, even though he supported the royal prerogative.[10] Despite his the troublesome independence of his views, Yelverton regained the trust of King James I by gaining audience and explaining his views.[11] Ultimately this reconciliation enabled him to serve the king in various capacities.[12] In 1613, Yelverton was made solicitor-general and knighted.[13] Ultimately, Yelverton became attorney general after the king appointed Sir Francis Bacon lord keeper.[14]

Despite his advancement to these positions of power, his puritan independence once again got him in trouble.[15] The Duke of Buckingham, with whom Yelverton had an adversarial relationship, accused him of abusing his position as commissioner of patents.[16] Their animosity came to a head when Yelverton accused Buckingham of standing “still att the Kinges elbowe ready to hew me down.”[17] Because of these words, Yelverton was found guilty of slandering Buckingham in addition to the underlying crime of impugning the king through his actions as commissioner of patents.[18] In 1621, Yelverton returned to the king’s bench, chancery, Star Chamber, and assize circuits.[19] In 1625 he was made serjeant-at-law and became judge of the court of common pleas, five years before he died.[20]

Scholars hold Yelverton’s Reports in high regard. Although they were never intended for publication, they are considered “among the best of the older books both for value of decision and essential accuracy of report.” [21]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Both Dean's Memo[22] and the Brown Bibliography[23] suggest Wythe owned the third (1735) edition of Yelverton's Reports based on notes in John Marshall's commonplace book.[24] The Wolf Law Library purchased a copy of the same edition.

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in recent period-style quarter calf over marbled boards with renewed endpapers. Includes early owner signature of "Miers Fischer" the front flyleaf and title page. Purchased from The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd.

View this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

References

- ↑ S. R. Gardiner, rev. Louis A. Knafla, “Yelverton, Sir Henry (b. 1566, d. 1630)”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed February 24, 2014.

- ↑ John William Wallace, The Reporters, Arranged and Characterized with Incidental Remarks, 4th ed., rev. and enl. (Boston: Soule and Bugbee, 1882), 212.

- ↑ Ibid. 214

- ↑ "Yelverton, Sir Henry," Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Wallace, The Reporters, 211.

- ↑ Memorandum from Barbara C. Dean, Colonial Williamsburg Found., to Mrs. Stiverson, Colonial Williamsburg Found. (June 16, 1975), 15 (on file at Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary).

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

- ↑ The Papers of John Marshall, eds. Herbert A. Johnson, Charles T. Cullen, and Nancy G. Harris (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, in association with the Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1974), 1:45.

External Links

Read this book in Google Books.