Difference between revisions of "De Rerum Natura"

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

}}Titus Lucretius Carus (c.99-c.55BCE), known simply as Lucretius, was a Roman poet and ardent believer in the physical system of Epicurus.<ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-1847 "Lucrē'tius”] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'', ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> The Epicurean philosophy is a “strictly mechanistic account of all phenoma” that atoms, which are extremely small, are unchanging and indestructible and make up everything in the world from physical objects to the mind to the soul.<ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-1173 "Epicū'rus”] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'', ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> Everything in the world is made up of these atomic compounds—including the gods who should be respected and admired but are not responsible for nature—which disperse and then form something else when a being dies.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Besides his philosopher status, little is known about Lucretius though various contemporary writers claim knowledge of him.<ref>"Lucrē'tius” in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature''.</ref><br/> | }}Titus Lucretius Carus (c.99-c.55BCE), known simply as Lucretius, was a Roman poet and ardent believer in the physical system of Epicurus.<ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-1847 "Lucrē'tius”] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'', ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> The Epicurean philosophy is a “strictly mechanistic account of all phenoma” that atoms, which are extremely small, are unchanging and indestructible and make up everything in the world from physical objects to the mind to the soul.<ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001/acref-9780199548545-e-1173 "Epicū'rus”] in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature'', ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).</ref> Everything in the world is made up of these atomic compounds—including the gods who should be respected and admired but are not responsible for nature—which disperse and then form something else when a being dies.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Besides his philosopher status, little is known about Lucretius though various contemporary writers claim knowledge of him.<ref>"Lucrē'tius” in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature''.</ref><br/> | ||

<br/>''De Rerum Natura'', or “On Nature,” the only known work of Lucretius, is a poem in six books which is also the best surviving work explaining Epicureanism though the sources are unknown and it is unlikely to include Epicurus’s own work.<ref>Ibid.</ref> “The purpose of the poem is to free men from a sense of guilt and the fear of death by demonstrating that fear of the intervention of gods in this world and of punishment of the soul after death are groundless: the world and everything in it are material and governed by the mechanical laws of nature, and the soul is mortal and perishes with the body.”<ref>Ibid.</ref> Lucretius wrote with a clear and organizational purpose as even “[the] division of the text corresponds to the Epicurean stress on the intelligibility of phenomena: everything has a systematic explanation, the world can be analysed and understood.”<ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192801463.001.0001/acref-9780192801463-e-1313 "Lucrētius"] in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World'', ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).</ref> Each book has a prologue and a conclusion, with a greater prologue in Book 1 which “opens with a famous invocation of Venus, goddess of creative life, to grant to the poet inspiration and to Rome peace.”<ref>"Lucrē'tius” in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature''.</ref> Book 6 was intended as the final book, demonstrated by the explicit statement to that end in the prologue, though it was likely incomplete at Lucretius’s death and therefore published as it was.<ref>Ibid.</ref><br/> | <br/>''De Rerum Natura'', or “On Nature,” the only known work of Lucretius, is a poem in six books which is also the best surviving work explaining Epicureanism though the sources are unknown and it is unlikely to include Epicurus’s own work.<ref>Ibid.</ref> “The purpose of the poem is to free men from a sense of guilt and the fear of death by demonstrating that fear of the intervention of gods in this world and of punishment of the soul after death are groundless: the world and everything in it are material and governed by the mechanical laws of nature, and the soul is mortal and perishes with the body.”<ref>Ibid.</ref> Lucretius wrote with a clear and organizational purpose as even “[the] division of the text corresponds to the Epicurean stress on the intelligibility of phenomena: everything has a systematic explanation, the world can be analysed and understood.”<ref>[http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192801463.001.0001/acref-9780192801463-e-1313 "Lucrētius"] in ''Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World'', ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).</ref> Each book has a prologue and a conclusion, with a greater prologue in Book 1 which “opens with a famous invocation of Venus, goddess of creative life, to grant to the poet inspiration and to Rome peace.”<ref>"Lucrē'tius” in ''The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature''.</ref> Book 6 was intended as the final book, demonstrated by the explicit statement to that end in the prologue, though it was likely incomplete at Lucretius’s death and therefore published as it was.<ref>Ibid.</ref><br/> | ||

| − | <br/>This work is an edition of Lucretius’s ''De Rerum Natura'' published in 1759 by two well-known and regarded Scottish publishers | + | <br/>This work is an edition of Lucretius’s ''De Rerum Natura'' published in 1759 by two well-known and regarded Scottish publishers, Robert and Andrew Foulis. |

Revision as of 16:39, 27 February 2014

Titi Lucretii Cari De Rerum Natura Libri Sex: ex Editione Thomae Creech

by Titus Lucretius Carus

| De Rerum Natura | |

|

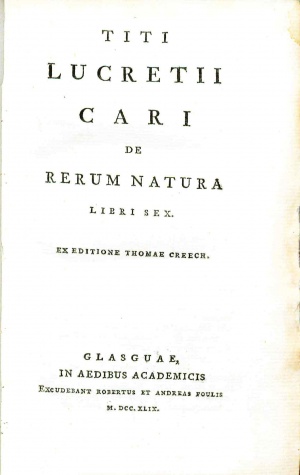

Title page from De Rerum Natura, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Titus Lucretius Carus |

| Published | Glasguae: In Aedibus Academicis : Excudebant Robertus et Andreas Foulis ... |

| Date | 1759 |

| Language | Latin |

Titus Lucretius Carus (c.99-c.55BCE), known simply as Lucretius, was a Roman poet and ardent believer in the physical system of Epicurus.[1] The Epicurean philosophy is a “strictly mechanistic account of all phenoma” that atoms, which are extremely small, are unchanging and indestructible and make up everything in the world from physical objects to the mind to the soul.[2] Everything in the world is made up of these atomic compounds—including the gods who should be respected and admired but are not responsible for nature—which disperse and then form something else when a being dies.[3] Besides his philosopher status, little is known about Lucretius though various contemporary writers claim knowledge of him.[4]

De Rerum Natura, or “On Nature,” the only known work of Lucretius, is a poem in six books which is also the best surviving work explaining Epicureanism though the sources are unknown and it is unlikely to include Epicurus’s own work.[5] “The purpose of the poem is to free men from a sense of guilt and the fear of death by demonstrating that fear of the intervention of gods in this world and of punishment of the soul after death are groundless: the world and everything in it are material and governed by the mechanical laws of nature, and the soul is mortal and perishes with the body.”[6] Lucretius wrote with a clear and organizational purpose as even “[the] division of the text corresponds to the Epicurean stress on the intelligibility of phenomena: everything has a systematic explanation, the world can be analysed and understood.”[7] Each book has a prologue and a conclusion, with a greater prologue in Book 1 which “opens with a famous invocation of Venus, goddess of creative life, to grant to the poet inspiration and to Rome peace.”[8] Book 6 was intended as the final book, demonstrated by the explicit statement to that end in the prologue, though it was likely incomplete at Lucretius’s death and therefore published as it was.[9]

This work is an edition of Lucretius’s De Rerum Natura published in 1759 by two well-known and regarded Scottish publishers, Robert and Andrew Foulis.

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

Bound in contemporary full brown calf. Spine features red morocco label, gilt lettering and decoration. Gilt rolls to board edges.

References

- ↑ "Lucrē'tius” in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- ↑ "Epicū'rus” in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, ed. by M.C. Howatson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ "Lucrē'tius” in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ "Lucrētius" in Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World, ed. by John Roberts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- ↑ "Lucrē'tius” in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature.

- ↑ Ibid.