Difference between revisions of "Spectator"

(→by Joseph Addison and Sir Richard Steele, ed.) |

(→by Joseph Addison and Sir Richard Steele, ed.) |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

Steele entered Parliament in 1713 as a member of the Whig party.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Only a year after taking his seat, Steele was expelled from Parliament by his political rivals but returned in 1715 as a Hanoverian and was soon after knighted.<ref>Chambers Biographical Dictionary, ''Steele, Sir Richard''.</ref> After a political dispute in 1719 with Addison relating to the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1719_in_Great_Britain Peerage Bill], Steele attempted to reconcile the friendship but Addison died the same year.<ref>The Columbia Encyclopedia, Steele, ''Sir Richard''.</ref> Forced to retire to Wales in 1724 due to increasing debt, Steele died in 1729 in relative obscurity.<ref>Ibid.</ref> | Steele entered Parliament in 1713 as a member of the Whig party.<ref>Ibid.</ref> Only a year after taking his seat, Steele was expelled from Parliament by his political rivals but returned in 1715 as a Hanoverian and was soon after knighted.<ref>Chambers Biographical Dictionary, ''Steele, Sir Richard''.</ref> After a political dispute in 1719 with Addison relating to the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1719_in_Great_Britain Peerage Bill], Steele attempted to reconcile the friendship but Addison died the same year.<ref>The Columbia Encyclopedia, Steele, ''Sir Richard''.</ref> Forced to retire to Wales in 1724 due to increasing debt, Steele died in 1729 in relative obscurity.<ref>Ibid.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Many contemporary scholars, including Scott Paul Gordon, view the Spectator as an early catalyst for shaping the social norms and principles of politeness of the growing middle class in England. Gordon contends that Mr. Spectator encouraged readers to critically examine themselves in light of others and to alter one’s public actions and social interactions to fit an ideal public behavior, but in such a way that forwarded self-interest.<ref>Gordon, Scott Paul. The Power of the Passive Self in English Literature, 1640-1770. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002, 87. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), EBSCOhost (accessed May 27, 2015).</ref> In the publications, an individual’s public behavior was portrayed as strategically adjusted to fit any given audience.<ref>Ibid., 88.</ref> Therefore emphasis was placed less on personal authenticity and more on increasing one’s reputation and social standing. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 10:48, 27 May 2015

by Joseph Addison and Sir Richard Steele, ed.

| The Spectator | ||

|

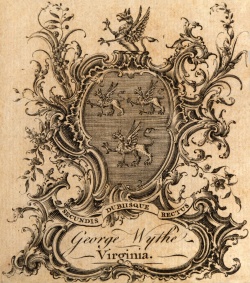

at the College of William & Mary. |

||

| Editor | Joseph Addison and Sir Richard Steele | |

| Edition | ? | |

Precise edition unknown.

Joseph Addison (1672-1719) was an English poet, dramatist, essayist, and statesman. Before distinguishing himself as a classical scholar at Oxford, he was classmates with Richard Steele at Charterhouse.[1] Addison first rose to national prominence after publishing The Campaign (1704), an epic poem depicting the Duke of Marlborough’s victory at Blenheim.[2] His literary success led to his selection as undersecretary of state in 1705 and subsequent appointment as secretary to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1709.[3] He also obtained a seat in Parliament from Malmesbury in 1708 which he held until his death.[4] Later, in 1717, Addison was chosen to serve as secretary of state, a post he resigned a year later in 1718 due to poor health (Ibid).

Although a prominent statesman, Addison is mostly remembered for his work as an essayist. In addition to cofounding The Spectator with Richard Steele in March of 1711, he also contributed to Steel’s publications, Tatler and the Guardian.[5][6] He wrote in a simple, orderly, and precise manner in order to engage his readers and inspire reasonable thinking and debate.[7] He achieved great success and fame during his lifetime and his publications are credited with raising the level of technical precision for English essayists.[8] Yet during the period from 1714 to his death in 1719, Addison quarreled with Steele and was plagued by poor health and a unhappy marriage [9].

Born in Dublin, Richard Steele (1672-1729) was an English playwright and essayist. After completing his studies alongside Joseph Addison at Charterhouse and later at Oxford, Steele began a career in the army in 1694 and obtained the rank of captain by 1701.[10] After serving in the army and low level government positions, he founded his renowned periodical, Tatler, in 1709.[11] He also cofounded The Spectator with Addison in 1711 and founded the Guardian in 1713.[12] Although Steele differed from Addison in temperament, their shared political beliefs and goals allowed them to form one of the greatest literary partnerships in the English language. He lacked Addison’s technical prowess but wrote with a style that was charming, imaginative, and witty.[13]

Steele entered Parliament in 1713 as a member of the Whig party.[14] Only a year after taking his seat, Steele was expelled from Parliament by his political rivals but returned in 1715 as a Hanoverian and was soon after knighted.[15] After a political dispute in 1719 with Addison relating to the Peerage Bill, Steele attempted to reconcile the friendship but Addison died the same year.[16] Forced to retire to Wales in 1724 due to increasing debt, Steele died in 1729 in relative obscurity.[17]

Many contemporary scholars, including Scott Paul Gordon, view the Spectator as an early catalyst for shaping the social norms and principles of politeness of the growing middle class in England. Gordon contends that Mr. Spectator encouraged readers to critically examine themselves in light of others and to alter one’s public actions and social interactions to fit an ideal public behavior, but in such a way that forwarded self-interest.[18] In the publications, an individual’s public behavior was portrayed as strategically adjusted to fit any given audience.[19] Therefore emphasis was placed less on personal authenticity and more on increasing one’s reputation and social standing.

References

- ↑ "Addison, Joseph". 2015. In The Columbia Encyclopedia. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ↑ "Addison, Joseph". 2011. In Chambers Biographical Dictionary. London: Chambers Harrap.

- ↑ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Addison, Joseph.

- ↑ Chambers Biographical Dictionary,Addison, Joseph.

- ↑ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Addison, Joseph.

- ↑ Chambers Biographical Dictionary, Addison, Joseph

- ↑ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Addison, Joseph.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Steele, Sir Richard. (2015). In The Columbia Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- ↑ "Steele, Sir Richard". 2011. In Chambers Biographical Dictionary. London: Chambers Harrap.

- ↑ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Steele, Sir Richard.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Chambers Biographical Dictionary, Steele, Sir Richard.

- ↑ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Steele, Sir Richard.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Gordon, Scott Paul. The Power of the Passive Self in English Literature, 1640-1770. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002, 87. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), EBSCOhost (accessed May 27, 2015).

- ↑ Ibid., 88.