Difference between revisions of "George Wythe the Colonial Briton"

Dbthompson (talk | contribs) (→Page 80) |

m |

||

| (383 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE: "George Wythe the Colonial Briton: A Biographical Study of the Pre-Revolutionary Era in Virginia"}} | {{DISPLAYTITLE: "George Wythe the Colonial Briton: A Biographical Study of the Pre-Revolutionary Era in Virginia"}} | ||

| + | ===by William Edwin Hemphill=== | ||

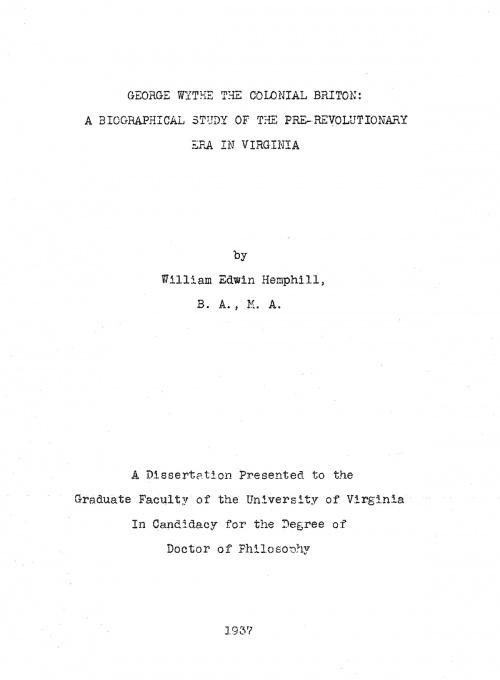

[[File:HemphillGeorgeWytheTheColonialBriton1937Title.jpg|thumb|right|500px|Title page from Hemphill's 1937 doctoral dissertation, "[[Media:HemphillGeorgeWytheTheColonialBriton1937.pdf|George Wythe the Colonial Briton: A Biographical Study of the Pre-Revolutionary Era in Virginia]]" (18MB PDF).]] | [[File:HemphillGeorgeWytheTheColonialBriton1937Title.jpg|thumb|right|500px|Title page from Hemphill's 1937 doctoral dissertation, "[[Media:HemphillGeorgeWytheTheColonialBriton1937.pdf|George Wythe the Colonial Briton: A Biographical Study of the Pre-Revolutionary Era in Virginia]]" (18MB PDF).]] | ||

| − | "[[Media:HemphillGeorgeWytheTheColonialBriton1937.pdf|George Wythe the Colonial Briton]]" is a 1937 dissertation by [[ | + | "[[Media:HemphillGeorgeWytheTheColonialBriton1937.pdf|George Wythe the Colonial Briton]]" is a 1937 dissertation by [[W. Edwin Hemphill]] (1912 – 1983), for a doctoral degree from the [http://www.virginia.edu/ University of Virginia].<ref>William Edwin Hemphill, "George Wythe the Colonial Briton: A Biographical Study of the Pre-Revolutionary Era in Virginia," PhD diss., University of Virginia, 1937. Used with permission.</ref> Hemphill was an archivist, historian, and editor, and contributed greatly to [[George Wythe]] scholarship, among his other historical pursuits. In 1933, he received a M.A. from [http://www.emory.edu/ Emory University,] with a [[George Wythe, America's First Law Professor|thesis also on George Wythe]]."<ref>Hemphill, "[[Media:HemphillGeorgeWytheAmericasFirstLawProfessor1933.pdf|George Wythe: America's First Law Professor and the Teacher of Jefferson, Marshall and Clay]]," master's thesis, Emory University, 1933.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | Hemphill states in his preface that he had originally intended to write a full biography of Wythe's life, but due to a "superabundance" of available material, was forced to limit himself to the first fifty years. The dissertation traces Wythe's movements and career through documentary evidence, court records, and letters, from his early life and self-education as a country lawyer, to his election to the House of Burgesses of Virginia and opposition to the [[wikipedia:Stamp Act 1765|Stamp Act]], and finally his appointment as Clerk of the House on the eve of the [[wikipedia:American Revolution|American Revolution]]. The dissertation is presented here with permission, in its entirety:<ref>A note on the hypertext: Hemphill's original dissertation was typewritten, and his ''sic erat scriptum'' notes for errors in transcribed works will appear underlined, as "[<u>sic</u>]". Notes made for the Wythepedia transcription of the original typescript appear in italics, thusly: "[''sic'']".</ref> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Full text=== | ===Full text=== | ||

*[[Media:HemphillGeorgeWytheTheColonialBriton1937.pdf|PDF]] (18MB) | *[[Media:HemphillGeorgeWytheTheColonialBriton1937.pdf|PDF]] (18MB) | ||

| − | * MS Word | + | *[[Media:HemphillGeorgeWytheTheColonialBriton1937.docx|MS Word]] (13MB) |

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| Line 353: | Line 354: | ||

The story of the research by which a historical study was pursued and produced is often more captivating than the the written product of the investigation. It might perhaps be deemed so of this treatise, were I to relate step by step half the recollections of the more pleasant, humorous, accidental, and miraculous episodes which I have experienced in this effort to discover and piece together the events of the first fifty years in the life of George Wythe (1726-1806). | The story of the research by which a historical study was pursued and produced is often more captivating than the the written product of the investigation. It might perhaps be deemed so of this treatise, were I to relate step by step half the recollections of the more pleasant, humorous, accidental, and miraculous episodes which I have experienced in this effort to discover and piece together the events of the first fifty years in the life of George Wythe (1726-1806). | ||

| − | This dissertation had a remote and unwitting origin six full years ago. In the spring of 1931 Mr. Frank L. Jones, of New York City, Vice-President of the Equitable Life Assurance Society, sponsored among Hampden-Sydney College students an essay contest on Wythe. During the course of preparing for that competition a rather puerile paper, which contained not a single original fact or thought, it occurred to me that George Wythe had | + | This dissertation had a remote and unwitting origin six full years ago. In the spring of 1931 Mr. Frank L. Jones, of New York City, Vice-President of the Equitable Life Assurance Society, sponsored among Hampden-Sydney College students an essay contest on Wythe. During the course of preparing for that competition a rather puerile paper, which contained not a single original fact or thought, it occurred to me that George Wythe had as good a claim as any of his contemporaries in the golden age of Virginia leadership to the title of the "Forgotten Man". That idea — itself little more original than the research which was its spawning-ground — has undergone no material amendment despite its more recent subjection to critical comparative examination. I still believe the thought centered upon Wythe by his score of biographical homilists and by the public to be far from commensurate with the nobility of his character and the value of his contributions to American institutions. |

The research requirements for a master's degree and the willingness of my history professors at Emory University to sanction a more thorough exploration of the subject which had become my primary intellectual interest combined to promote another excursion in the Wythe field. The tangible result was a thesis on portions of Wythe's influence as an educator, written in the spring of 1933 under the descriptive title "[[George Wythe, America's First Law Professor|George Wythe, America's First Law Professor and the Teacher of Jefferson, Marshall, and Clay]]". Since that study Wythe has never really been relegated to the back of my mind, though other academic hurdles and various employments which were professionally and financially welcome necessarily forestalled undivided attention to him during all but about ten months of the past four years. | The research requirements for a master's degree and the willingness of my history professors at Emory University to sanction a more thorough exploration of the subject which had become my primary intellectual interest combined to promote another excursion in the Wythe field. The tangible result was a thesis on portions of Wythe's influence as an educator, written in the spring of 1933 under the descriptive title "[[George Wythe, America's First Law Professor|George Wythe, America's First Law Professor and the Teacher of Jefferson, Marshall, and Clay]]". Since that study Wythe has never really been relegated to the back of my mind, though other academic hurdles and various employments which were professionally and financially welcome necessarily forestalled undivided attention to him during all but about ten months of the past four years. | ||

| Line 399: | Line 400: | ||

===Page 2=== | ===Page 2=== | ||

| + | [[File:TylerHistoryOfHampton1922Title.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Title page from Lyon G. Tyler's ''[[History of Hampton and Elizabeth City County Virginia]]'' (Hampton, VA: Board of Supervisors of Elizabeth City County, 1922).]] | ||

by the settlers' inability to foresee the future, might well have ended at [[wikipedia:Kecoughtan, Virginia|Kecoughtan's]] "Strawberry Bank", the fertile area adjoining [[wikipedia:Old Point Comfort|Cape Comfort]], between Hampton River and Mill Creek, whose few amicable natives found it quite easy to secure wild and domestic foods in bountiful quantities from nearby corn fields, forests, and waters. However, probably in fear of hostile raids by Spanish vessels (a threat which never materialized), the expedition pressed up the James River to an unhealthy and unproductive morass which it named [[wikipedia:Jamestown, Virginia|Jamestown]], an island affording little better protection from Spaniards and Indians to counterbalance the great advantage of Kecoughtan as a salubrious and fruitful site. Thus during the next three years Kecoughtan served the cause of British colonization chiefly as a place at which Captain John Smith and others travelling to and fro in the James could stop over for lodging and feasting. During the summer of 1610 the Kecoughtans were driven away forever from the locality in mysterious reprisal for the murder of a white man by members of another tribe, and some of the colonists moved in from later depopulated Jamestown — on which fact the present city of Hampton bases its claim to the oldest continuous English-speaking settlement in the New World.<sup>1</sup> | by the settlers' inability to foresee the future, might well have ended at [[wikipedia:Kecoughtan, Virginia|Kecoughtan's]] "Strawberry Bank", the fertile area adjoining [[wikipedia:Old Point Comfort|Cape Comfort]], between Hampton River and Mill Creek, whose few amicable natives found it quite easy to secure wild and domestic foods in bountiful quantities from nearby corn fields, forests, and waters. However, probably in fear of hostile raids by Spanish vessels (a threat which never materialized), the expedition pressed up the James River to an unhealthy and unproductive morass which it named [[wikipedia:Jamestown, Virginia|Jamestown]], an island affording little better protection from Spaniards and Indians to counterbalance the great advantage of Kecoughtan as a salubrious and fruitful site. Thus during the next three years Kecoughtan served the cause of British colonization chiefly as a place at which Captain John Smith and others travelling to and fro in the James could stop over for lodging and feasting. During the summer of 1610 the Kecoughtans were driven away forever from the locality in mysterious reprisal for the murder of a white man by members of another tribe, and some of the colonists moved in from later depopulated Jamestown — on which fact the present city of Hampton bases its claim to the oldest continuous English-speaking settlement in the New World.<sup>1</sup> | ||

| Line 421: | Line 423: | ||

===Page 4=== | ===Page 4=== | ||

| − | eight governmental units. As if it had not already sufficient claims to priority, during the following year, 1634/5,<sup>1</sup> Benjamin Syms endowed the first educational institution in the | + | eight governmental units. As if it had not already sufficient claims to priority, during the following year, 1634/5,<sup>1</sup> Benjamin Syms endowed the first educational institution in the New World, and in 1638 Thomas Eaton in a somewhat similar benefaction surpassed Syms' philanthropy. Through the [http://crgis.ndc.nasa.gov/historic/Syms_Free_School_Site Syms Free School] and the [[wikipedia:Syms-Eaton Academy|Eaton Charity School]], whose doors were open for many a decade, [[wikipedia:Elizabeth City (Virginia Company)|Elizabeth City]] antedated slightly the notable legacy of [[wikipedia:John Harvard (clergyman)|John Harvard]].<sup>2</sup> |

The steady influx of immigrants into the county increased its population before the close of the seventeenth century to about 800 people. Among them, fostered by an ideal location and by the best maritime facilities then available, a flourishing commercial life developed in conjunction | The steady influx of immigrants into the county increased its population before the close of the seventeenth century to about 800 people. Among them, fostered by an ideal location and by the best maritime facilities then available, a flourishing commercial life developed in conjunction | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| − | 1. Until the British adoption in 1752 of the Gregorian calendar, a revision of the less accurate Julian calendar, the new year began among English peoples late in March. Thus, according to present reckoning, February 12, 1634, was actually in the year 1635. The generally current practice of making a double notation of years in the overlapping period (<u>e.g</u>., March 1, 1750/1) — in preference to the more antiquated method of signifying Old Style dates as March 1, 1750 (O.S.) — has been adopted throughout these pages. | + | 1. Until the British adoption in 1752 of the [[wikipedia:Gregorian calendar|Gregorian calendar]], a revision of the less accurate [[wikipedia:Julian calendar|Julian calendar]], the new year began among English peoples late in March. Thus, according to present reckoning, February 12, 1634, was actually in the year 1635. The generally current practice of making a double notation of years in the overlapping period (<u>e.g</u>., March 1, 1750/1) — in preference to the more antiquated method of signifying Old Style dates as March 1, 1750 (O.S.) — has been adopted throughout these pages. |

| − | 2. Tyler, [[History of Hampton and Elizabeth City County Virginia|<u>History of Hampton</u>]], 22-23; Starkey, First Plantation, 13. Governor William Berkeley, Virginia's counterpart of Charles II, was evidently quite ill-informed in one respect when he made his oft-quoted report in 1671, "But, I thank God, <u>there are no free schools</u> nor <u>printing</u> [in this colony] and I hope we shall not have [them] these hundred years; for <u>learning</u> has brought disobedience, and heresy, and sects into the world, and printing has divulged them, and libels against the best government. God keep us from both!": William Waller Hening, ed. <u>The Statutes at Large; being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia ...</u>, II, 517. Here, as always in later pages, the italics are in the original. This collection will hereafter be cited as Hening, <u>Statutes</u>. | + | 2. Tyler, [[History of Hampton and Elizabeth City County Virginia|<u>History of Hampton</u>]], 22-23; Starkey, First Plantation, 13. Governor William Berkeley, Virginia's counterpart of [[wikipedia:Charles II of England|Charles II]], was evidently quite ill-informed in one respect when he made his oft-quoted report in 1671, "But, I thank God, <u>there are no free schools</u> nor <u>printing</u> [in this colony] and I hope we shall not have [them] these hundred years; for <u>learning</u> has brought disobedience, and heresy, and sects into the world, and printing has divulged them, and libels against the best government. God keep us from both!": William Waller Hening, ed. <u>The Statutes at Large; being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia ...</u>, II, 517. Here, as always in later pages, the italics are in the original. This collection will hereafter be cited as Hening, <u>Statutes</u>. |

===Page 5=== | ===Page 5=== | ||

| Line 450: | Line 452: | ||

American Revolution a reliable hint of gentility.<sup>1</sup> | American Revolution a reliable hint of gentility.<sup>1</sup> | ||

| − | The original Wythe immigrant, great-grandfather of George in a direct line of succession,<sup>2</sup> was Thomas Wythe, whom for clarity's sake, since his sons for three generations also bore that name, it is perhaps best to call Thomas the First. He moved into [[wikipedia:Elizabeth City County, Virginia|Elizabeth City County]] in or a few years before 1680,<sup>3</sup> probably after [[wikipedia:Bacon's Rebellion|Bacon's Rebellion]], the revolt in Virginia which preceded the [[wikipedia:American Revolution|American Revolution]] by exactly a century. He acquired a considerable acreage near the northern side of the peninsula beside [[wikipedia:Back River (Virginia)|Back River]] and established there the family estate known as "Chesterville".<sup>4</sup> | + | The original Wythe immigrant, great-grandfather of George in a direct line of succession,<sup>2</sup> was Thomas Wythe, whom for clarity's sake, since his sons for three generations also bore that name, it is perhaps best to call Thomas the First. He moved into [[wikipedia:Elizabeth City County, Virginia|Elizabeth City County]] in or a few years before 1680,<sup>3</sup> probably after [[wikipedia:Bacon's Rebellion|Bacon's Rebellion]], the revolt in Virginia which preceded the [[wikipedia:American Revolution|American Revolution]] by exactly a century. He acquired a considerable acreage near the northern side of the peninsula beside [[wikipedia:Back River (Virginia)|Back River]] and established there the family estate known as "[[Chesterville]]".<sup>4</sup> |

---- | ---- | ||

| Line 463: | Line 465: | ||

===Page 7=== | ===Page 7=== | ||

| + | [[File:TylerWilliamAndMaryCollegeQuarterlyJuly1893P69.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Illustration of the Wythe family tree by Lyon G. Tyler, from "[[Ancestry of George Wythe, LL.D.|Ancestry of George Wythe, LL. D.]]," ''William and Mary College Quarterly'' 2, no. 1 (July 1893), 69.]] | ||

Early recognition came to the immigrant Wythe as one of the "best people in the community".<sup>1</sup> In 1680 he sat upon the bench of the monthly county court,<sup>2</sup> whose members held the title of justices of the peace and served as judges with jurisdiction over civil and criminal litigation. In this capacity, the county's highest local office, he determined <u>ex officio</u> the right and the wrong of his neighbors' petty disputes in the lesser magistrate's court.<sup>3</sup> It is of interest in this connection to mention the fact that his precedent in this respect was followed, as later pages will show, by every male inhabitant of [[wikipedia:Elizabeth City County, Virginia|Elizabeth City County]] who bore the name of Wythe. Moreover, Thomas the First was almost immediately elected a burgess to represent the county in the General Assembly, taking the usual oaths of office on June 9, 1680,<sup>4</sup> and receiving 200 pounds of tobacco, the approved currency of that day, as his legislative salary.<sup>5</sup> Thomas Wythe the First, | Early recognition came to the immigrant Wythe as one of the "best people in the community".<sup>1</sup> In 1680 he sat upon the bench of the monthly county court,<sup>2</sup> whose members held the title of justices of the peace and served as judges with jurisdiction over civil and criminal litigation. In this capacity, the county's highest local office, he determined <u>ex officio</u> the right and the wrong of his neighbors' petty disputes in the lesser magistrate's court.<sup>3</sup> It is of interest in this connection to mention the fact that his precedent in this respect was followed, as later pages will show, by every male inhabitant of [[wikipedia:Elizabeth City County, Virginia|Elizabeth City County]] who bore the name of Wythe. Moreover, Thomas the First was almost immediately elected a burgess to represent the county in the General Assembly, taking the usual oaths of office on June 9, 1680,<sup>4</sup> and receiving 200 pounds of tobacco, the approved currency of that day, as his legislative salary.<sup>5</sup> Thomas Wythe the First, | ||

| Line 576: | Line 579: | ||

===Page 15=== | ===Page 15=== | ||

| + | [[File:CallBiographicalSketchOfTheJudges1833pX.jpg|thumb|left|300px|[[Biographical Sketch of the Judges|George Wythe's biography]] from vol. 4 of ''Cases Decided in the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia,'' ed. Daniel Call (Richmond, VA: Robert I. Smith, 1833).]] | ||

made in the latter when he was about seventy years old, he toyed with the aged nautical problem of ascertaining one's position upon the high seas and introduced a new method for determining longitude.<sup>1</sup> A volume from his pen upon "mathematical and other subjects" was to be seen years later in George Wythe's library.<sup>2</sup> Lest anyone doubt that the published productions of that pen were voluminous, it may be mentioned that a printed bibliography of them covers thirty-six pages.<sup>3</sup> One of them, titled, <u>An Exhortation and Caution to Friends concerning Buying and Keeping of Negroes</u> (Philadelphia, 1693), has a definite claim to priority as the first Quaker pamphlet against slavery.<sup>4</sup> | made in the latter when he was about seventy years old, he toyed with the aged nautical problem of ascertaining one's position upon the high seas and introduced a new method for determining longitude.<sup>1</sup> A volume from his pen upon "mathematical and other subjects" was to be seen years later in George Wythe's library.<sup>2</sup> Lest anyone doubt that the published productions of that pen were voluminous, it may be mentioned that a printed bibliography of them covers thirty-six pages.<sup>3</sup> One of them, titled, <u>An Exhortation and Caution to Friends concerning Buying and Keeping of Negroes</u> (Philadelphia, 1693), has a definite claim to priority as the first Quaker pamphlet against slavery.<sup>4</sup> | ||

| Line 812: | Line 816: | ||

===Page 33=== | ===Page 33=== | ||

| − | There may be some exaggeration in the description of her as "a woman of uncommon knowledge and strength of mind" which ascribes to her so intimate an acquaintance with Latin that she spoke it "fluently",<sup>1</sup> but at least she, as a granddaughter of [[wikipedia:George Keith (missionary)|George Keith]], was not as illiterate as the mother and grandmother of her husband, neither of whom could sign her own name.<sup>2</sup> Wythe himself in later years attributed to his mother his initiation in the study of the Latin language,<sup>3</sup> but she taught him only the principles of grammar and, as he said, "to read the colloquies of <u>Corderius</u> very imperfectly...."<sup>4</sup> Another report has been handed through somewhat more indirect channels to the effect that she assisted his translations of the [[wikipedia:New Testament|New Testament]] in its | + | There may be some exaggeration in the description of her as "a woman of uncommon knowledge and strength of mind" which ascribes to her so intimate an acquaintance with Latin that she spoke it "fluently",<sup>1</sup> but at least she, as a granddaughter of [[wikipedia:George Keith (missionary)|George Keith]], was not as illiterate as the mother and grandmother of her husband, neither of whom could sign her own name.<sup>2</sup> Wythe himself in later years attributed to his mother his initiation in the study of the Latin language,<sup>3</sup> but she taught him only the principles of grammar and, as he said, "to read the colloquies of <u>Corderius</u> very imperfectly...."<sup>4</sup> Another report has been handed through somewhat more indirect channels to the effect that she assisted his translations of the [[wikipedia:New Testament|New Testament]] in its Greek text by referring when necessity demanded to an English version,<sup>5</sup> though she probably "knew of Greek only the alphabet and how to hold the dictionary...."<sup>6</sup> Thus George Wythe's maternal |

---- | ---- | ||

| Line 893: | Line 897: | ||

1. Call, "[[Biographical Sketch of the Judges|Judge Wythe]]", <u>loc. cit</u>., xi. | 1. Call, "[[Biographical Sketch of the Judges|Judge Wythe]]", <u>loc. cit</u>., xi. | ||

| − | 2. Benjamin B. Minor, "[[Memoir of the Author]]", George Wythe, <u>Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery...</u> ( | + | 2. Benjamin B. Minor, "[[Memoir of the Author]]", George Wythe, <u>Decisions of Cases in Virginia, by the High Court of Chancery ...</u> (2 nd ed.), xii. |

===Page 39=== | ===Page 39=== | ||

| Line 1,084: | Line 1,088: | ||

was his client in more than one suit.<sup>1</sup> | was his client in more than one suit.<sup>1</sup> | ||

| − | On the basis of these incomplete records it is safe to picture Wythe as a very successful attorney at law during 1747 and 1748, riding the circuit of the monthly courts from [[wikipedia:Caroline County, Virginia|Caroline County]], in the western Tidewater, on the east, through Spotsylvania and Orange to Augusta, in the Shenandoah Valley, on the west. He managed to make at least one visit to Elizabeth City, however, for in May, | + | On the basis of these incomplete records it is safe to picture Wythe as a very successful attorney at law during 1747 and 1748, riding the circuit of the monthly courts from [[wikipedia:Caroline County, Virginia|Caroline County]], in the western Tidewater, on the east, through Spotsylvania and Orange to Augusta, in the Shenandoah Valley, on the west. He managed to make at least one visit to Elizabeth City, however, for in May, 1748, he sold to George Wray a slave girl named Lucy for <s>L</s>23 5s, the court record of the transaction identifying him as "of the county of Spotsylvania, attorney at law".<sup>2</sup> Presumably, he was aided in getting his start as a practitioner by Zachary Lewis, perhaps living in Lewis' home. They must have often travelled together in the best of fellowship from courthouse to courthouse; locked horns, matched eloquence, and pitted wits against wits and argument against argument in dead earnest, upon arrival at a county seat, while upholding opposites sides of the same suit;<sup>3</sup> and ridden off together, upon adjournment, |

---- | ---- | ||

| Line 1,097: | Line 1,101: | ||

toward the next court to convene, regaling one another with mutually amusing observations, picking flaws in each other's pleas before the last bench, or plotting in silence a plan of campaign to best each other in forthcoming legal combats. Such, at least, was the relationship of some of their contemporaries in those days when law was in many respects America's most picturesque profession. | toward the next court to convene, regaling one another with mutually amusing observations, picking flaws in each other's pleas before the last bench, or plotting in silence a plan of campaign to best each other in forthcoming legal combats. Such, at least, was the relationship of some of their contemporaries in those days when law was in many respects America's most picturesque profession. | ||

| − | There was more, however, than the <u>camaraderie</u> of association at the bar to link together the lives of George Wythe and Zachary Lewis. Professional relationships were supplemented and made more personal by the marriage of the | + | There was more, however, than the <u>camaraderie</u> of association at the bar to link together the lives of George Wythe and Zachary Lewis. Professional relationships were supplemented and made more personal by the marriage of the twenty-one year old attorney to a daughter of his forty-five year old patron. |

Zachary Lewis had married Mary Waller (1699-1781) in the year of George Wythe's birth, under authority of a license dated January 3, 1725/6.<sup>1</sup> By their wedding Spotsylvania's two outstanding families were united, for the Wallers were as definitely stamped with the lineage and wealth of Piedmont aristocracy as the Lewises. Mary was the oldest child of Col. John Waller (<u>d</u>. 1753) of "Newport" and of his wife, Dorothy King. Her father had served in the first quarter of the century as sheriff, justice, and burgess of King William County before its western area had been given separate | Zachary Lewis had married Mary Waller (1699-1781) in the year of George Wythe's birth, under authority of a license dated January 3, 1725/6.<sup>1</sup> By their wedding Spotsylvania's two outstanding families were united, for the Wallers were as definitely stamped with the lineage and wealth of Piedmont aristocracy as the Lewises. Mary was the oldest child of Col. John Waller (<u>d</u>. 1753) of "Newport" and of his wife, Dorothy King. Her father had served in the first quarter of the century as sheriff, justice, and burgess of King William County before its western area had been given separate | ||

| Line 1,111: | Line 1,115: | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| − | 1. McIlwaine, ed., <u>Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1702-1712</u>, ix; McIlwaine, ed., <u>Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1712-1726</u>, vii, x; <u>William and Mary College Quarterly</u> (1st series), VIII, 79, IX, 63; Horace Edwin Hayden, <u>Virginia Genealogies</u>, 381. For an abstract of John Waller's will see Crozier, ed., <u>Virginia County Records</u>, I, 13-14; for abstracts relating to his sons see <u>ibid</u>., <u>passim</u>. Of them Edmund and John became clerks of SpotSylvania County, William was a colleague of Wythe and Zachary Lewis at the bar, and Benjamin moved to Williamsburg and became a judge of the admiralty court and a burgess for a number of years. | + | 1. McIlwaine, ed., <u>Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1702-1712</u>, ix; McIlwaine, ed., <u>Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1712-1726</u>, vii, x; <u>William and Mary College Quarterly</u> (1st series), VIII, 79, IX, 63; Horace Edwin Hayden, <u>[[Virginia Genealogies]]</u>, 381. For an abstract of John Waller's will see Crozier, ed., <u>Virginia County Records</u>, I, 13-14; for abstracts relating to his sons see <u>ibid</u>., <u>passim</u>. Of them Edmund and John became clerks of SpotSylvania County, William was a colleague of Wythe and Zachary Lewis at the bar, and Benjamin moved to Williamsburg and became a judge of the admiralty court and a burgess for a number of years. |

2. Hayden, <u>op. cit</u>., 381; McAllister and Tandy, <u>op. cit</u>., 134-135. She received a legacy in 1783: Crozier, ed., <u>Virginia County Records</u>, I, 5; with her father, her brother John, or her sister Mary she witnessed deeds of her uncles, Edmund and John Waller: <u>ibid</u>., 154, 158. For some information on her brothers and sisters see <u>ibid</u>., 30, 30, 41; <u>Tyler's Quarterly Magazine</u>, IV, 439; Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia (Photostats), May 7, 1773, University of Virginia Library. | 2. Hayden, <u>op. cit</u>., 381; McAllister and Tandy, <u>op. cit</u>., 134-135. She received a legacy in 1783: Crozier, ed., <u>Virginia County Records</u>, I, 5; with her father, her brother John, or her sister Mary she witnessed deeds of her uncles, Edmund and John Waller: <u>ibid</u>., 154, 158. For some information on her brothers and sisters see <u>ibid</u>., 30, 30, 41; <u>Tyler's Quarterly Magazine</u>, IV, 439; Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia (Photostats), May 7, 1773, University of Virginia Library. | ||

| Line 1,236: | Line 1,240: | ||

===Page 61=== | ===Page 61=== | ||

| − | imputation that he deserved at his comparatively immature age a smaller measure of good fortune. In 1754 an appropriation of | + | imputation that he deserved at his comparatively immature age a smaller measure of good fortune. In 1754 an appropriation of <s>L</s>20,000 was passed to help finance the current war against the French in the West. But such generous cooperation was circumscribed by an almost unprecedented condition: in the disbursement of these funds His Majesty's lieutenant-governor, who alone had previously superintended colonial expenditures, should act in conjunction with a special committee of directors, on which Wythe was the junior member named by the General Assembly.<sup>1</sup> When a sum twice as large was made available in the following year on the same terms, Wythe was again among those to whom the House delegated the assignment of guarding against the possibility that it might not be so expended as to render greatest aid to England's cause.<sup>2</sup> Upon a reorganization of four standing committees in 1755, to consider an accumulation of provincial business which had piled up under the exigencies of international conflict, he was given a place as the newest member of the three major subdivisions — the committees on Privileges and Elections |

---- | ---- | ||

| Line 1,254: | Line 1,258: | ||

Before he had reached the age of thirty [[George Wythe]] became intimately entangled in the long series of constitutional conflicts between the [[wikipedia:House of Burgesses|House of Burgesses]] and England's royal government which recurred periodically until the colony of Virginia became an independent commonwealth. The first of these was the pistole fee crisis. In it he attained a rank higher and more honorable than that of a burgess — but it was a position gained under circumstances peculiar and ticklish, literally reeking with possibilities for misinterpretation and jealousy. | Before he had reached the age of thirty [[George Wythe]] became intimately entangled in the long series of constitutional conflicts between the [[wikipedia:House of Burgesses|House of Burgesses]] and England's royal government which recurred periodically until the colony of Virginia became an independent commonwealth. The first of these was the pistole fee crisis. In it he attained a rank higher and more honorable than that of a burgess — but it was a position gained under circumstances peculiar and ticklish, literally reeking with possibilities for misinterpretation and jealousy. | ||

| − | His Majesty had delegated the choicest of thirteen continental plums of colonial patronage to the [[wikipedia:Willem van Keppel, 2nd Earl of Albemarle|Earl of Albemarle]], who held the title of [[wikipedia:List of colonial governors of Virginia|Governor General of Virginia]] but continued his residence in | + | His Majesty had delegated the choicest of thirteen continental plums of colonial patronage to the [[wikipedia:Willem van Keppel, 2nd Earl of Albemarle|Earl of Albemarle]], who held the title of [[wikipedia:List of colonial governors of Virginia|Governor General of Virginia]] but continued his residence in England. It was then customary among such appointees to sublet the actual supervision of a colony's affairs to one of their own favorites, who held the |

---- | ---- | ||

| Line 1,285: | Line 1,289: | ||

established law.<sup>1</sup> Ignoring the issue of valid law enforcement which was at the bottom of the controversy, the House thus elected wisely to fight the whole battle on the most vulnerable flank of [[wikipedia:Robert Dinwiddie|Dinwiddie's]] position — the question whether or not he had a right to extort by proclamation a fee for the use of the public seal. A few days later it resolved that any person paying a pistole for a land patent should be deemed a "Betrayer of the Rights and Privileges of the People" and determined to send an agent to the English court as a messenger for its claims.<sup>2</sup> | established law.<sup>1</sup> Ignoring the issue of valid law enforcement which was at the bottom of the controversy, the House thus elected wisely to fight the whole battle on the most vulnerable flank of [[wikipedia:Robert Dinwiddie|Dinwiddie's]] position — the question whether or not he had a right to extort by proclamation a fee for the use of the public seal. A few days later it resolved that any person paying a pistole for a land patent should be deemed a "Betrayer of the Rights and Privileges of the People" and determined to send an agent to the English court as a messenger for its claims.<sup>2</sup> | ||

| − | When the adamant lieutenant-governor, surprised at these unexpectedly forceful attacks,<sup>3</sup> and his loyal Council gave not one inch of ground,<sup>4</sup> the Burgesses proceeded to the selection of their agent. [[wikipedia:Peyton Randolph|Peyton Randolph]] (1721-1775), representative of corporate [http://www.wm.edu/ William and Mary College], which had a sort of "rotten borough" seat in the House, was chosen, and it was resolved that he should be paid | + | When the adamant lieutenant-governor, surprised at these unexpectedly forceful attacks,<sup>3</sup> and his loyal Council gave not one inch of ground,<sup>4</sup> the Burgesses proceeded to the selection of their agent. [[wikipedia:Peyton Randolph|Peyton Randolph]] (1721-1775), representative of corporate [http://www.wm.edu/ William and Mary College], which had a sort of "rotten borough" seat in the House, was chosen, and it was resolved that he should be paid <s>L</s>2500 from the public |

---- | ---- | ||

| Line 1,346: | Line 1,350: | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| − | 1. <u>Cf</u>. <u>e.g</u>., Brock, ed., <u>Records of Dinwiddie</u>, I, x; McIlwaine, ed., <u>Journals of the House of Burgesses</u> | + | 1. <u>Cf</u>. <u>e.g</u>., Brock, ed., <u>Records of Dinwiddie</u>, I, x; McIlwaine, ed., <u>Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1752-1758</u>, xx. |

===Page 70=== | ===Page 70=== | ||

| Line 1,387: | Line 1,391: | ||

Wythe was saved from the obligation to resign, with the consequent danger of having to explain a cancellation of his previous acceptance, by the commands from abroad that Randolph be given a second appointment. Doubtless it was [[wikipedia:Robert Dinwiddie|Dinwiddie]] who had to face the agony of apologetic explanations. | Wythe was saved from the obligation to resign, with the consequent danger of having to explain a cancellation of his previous acceptance, by the commands from abroad that Randolph be given a second appointment. Doubtless it was [[wikipedia:Robert Dinwiddie|Dinwiddie]] who had to face the agony of apologetic explanations. | ||

| − | Whether or not Wythe accepted the lieutenant-governor's appointment with professions of loyalty to one or more of the Burgesses, his position during 1754 was a treacherous one. One misstep might have turned against him the irascible Dinwiddie, whose temperament was not bettered by ill-health, and lost for him the benefits of royal patronage and of the Attorney-General's | + | Whether or not Wythe accepted the lieutenant-governor's appointment with professions of loyalty to one or more of the Burgesses, his position during 1754 was a treacherous one. One misstep might have turned against him the irascible Dinwiddie, whose temperament was not bettered by ill-health, and lost for him the benefits of royal patronage and of the Attorney-General's <s>L</s>140 annual salary. On the other hand, Virginians were quick to detect and condemn in appointees of the Crown sentiments which they considered prejudicial to their interests. In the heated atmosphere of 1754 Wythe had outwardly taken Dinwiddie's side, yet he seems to have steered safely the difficult course between a [[wikipedia:Scylla|Scylla]] and a [[wikipedia:Charybdis|Charybdis]]. So far as is known, he received no censure from the critical tongue or caustic pen of Dinwiddie. His selection late in the summer of 1754 by the freeholders of Williamsburg as their representative in the General Assembly and the assignments given him by the House during that and the following year are adequate testimony of the public's approval of his role in the pistole controversy. |

| Line 1,535: | Line 1,539: | ||

Wythe had become too intimately involved in the legislative and legal life of Williamsburg to consider very seriously a personal, permanent occupancy of "Chesterville". His political ties in the capital have already been enumerated; to these an advancement in the practise of his profession was added. Some time before May of 1755 he was admitted to the colony's supreme bar as an attorney before the semi-annual General Court.<sup>1</sup> No greater badge of distinction could be attained by a lawyer in Virginia's colonial period than the reputation of success in this superior tribunal of original and appellate jurisdiction, over which it was a primary duty of the lieutenant-governor to preside and in which the members of his Council sat as <u>ex officio</u> judges. | Wythe had become too intimately involved in the legislative and legal life of Williamsburg to consider very seriously a personal, permanent occupancy of "Chesterville". His political ties in the capital have already been enumerated; to these an advancement in the practise of his profession was added. Some time before May of 1755 he was admitted to the colony's supreme bar as an attorney before the semi-annual General Court.<sup>1</sup> No greater badge of distinction could be attained by a lawyer in Virginia's colonial period than the reputation of success in this superior tribunal of original and appellate jurisdiction, over which it was a primary duty of the lieutenant-governor to preside and in which the members of his Council sat as <u>ex officio</u> judges. | ||

| − | Another link in the chain which bound [[George Wythe]] to residence in | + | Another link in the chain which bound [[George Wythe]] to residence in Williamsburg was the blossoming of social interests there into a second marriage. After several years of widowerhood, probably about 1755, Wythe married [[Elizabeth Taliaferro Wythe|Elizabeth Taliaferro]], |

---- | ---- | ||

| − | 1. All the sketches of Wythe either ignore, evade, or falsify the time of his entrance to this court, the official records of which have never been available to scholars; when any information on the point has been given, it has been stated or implied that the date was 1756. But an earlier though indefinite date can be deductively established from the fact that Paul Carrington (1732/3-1818) received May, 1755, a license to practise law signed by [[wikipedia:Peyton Randolph|Peyton Randolph]], [[wikipedia:John Randolph (loyalist)|John Randolph]], and George Wythe: Alexander Brown, <u>The Cabells and Their Kin: a Memorial Volume of History, Biography and Genealogy</u>, 205. Since the official board of examiners could then consist only of judges of the General Court and of members of its bar, and since Wythe was never a member of the Council, it follows indubitably that he had gained admission to its bar before May, 1755. The original act of 1745 setting up the board of examiners had been renewed in 1748 without change in that respect: Hening, ed. <u>Statutes</u>, VI, 140-143. | + | 1. All the sketches of Wythe either ignore, evade, or falsify the time of his entrance to this court, the official records of which have never been available to scholars; when any information on the point has been given, it has been stated or implied that the date was 1756. But an earlier though indefinite date can be deductively established from the fact that Paul Carrington (1732/3-1818) received in May, 1755, a license to practise law signed by [[wikipedia:Peyton Randolph|Peyton Randolph]], [[wikipedia:John Randolph (loyalist)|John Randolph]], and George Wythe: Alexander Brown, <u>The Cabells and Their Kin: a Memorial Volume of History, Biography and Genealogy</u>, 205. Since the official board of examiners could then consist only of judges of the General Court and of members of its bar, and since Wythe was never a member of the Council, it follows indubitably that he had gained admission to its bar before May, 1755. The original act of 1745 setting up the board of examiners had been renewed in 1748 without change in that respect: Hening, ed. <u>Statutes</u>, VI, 140-143. |

===Page 78=== | ===Page 78=== | ||

| − | daughter of Richard and Eliza Eggleston Taliaferro.<sup>1</sup> Her father owned an estate called [http://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/jamesriver/pow.htm "Powhatan",] located in [[wikipedia:James City County, Virginia|James City County]] some four or five miles south of Williamsburg; he was a wealthy man, probably a "gentleman farmer" by vocation, an architect by avocation, and had been a judge of his county's court.<sup>2</sup> With his second bride it is possible, perhaps even likely, that he | + | daughter of Richard and Eliza Eggleston Taliaferro.<sup>1</sup> Her father owned an estate called [http://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/jamesriver/pow.htm "Powhatan",] located in [[wikipedia:James City County, Virginia|James City County]] some four or five miles south of Williamsburg; he was a wealthy man, probably a "gentleman farmer" by vocation, an architect by avocation, and had been a judge of his county's court.<sup>2</sup> With his second bride it is possible, perhaps even likely, that he secured the use of the [[George Wythe House|comfortable brick house]] which was for many years his home. Situated on the west side of the Palace Green, adjoining far-famed [http://www.brutonparish.org/ Bruton Parish Church,] less than a block from Duke of Gloucester Street, with the palatial Governor's Palace two blocks distant on the north, this handsome residence was built about 1755 by Wythe's second father-in-law. Under the terms of Richard Taliaferro's will its legal title was vested in his daughter and her husband.<sup>3</sup> |

---- | ---- | ||

| − | 1. Jefferson, "[[Notes for the Biography of George Wythe]]", filed under August 31, 1820, Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress; Hayden, <u>Virginia Genealogies</u>, 382; Tyler, "[[Great American Lawyers|George Wythe]]", <u>loc. cit</u>., 82-83, is authority for the date, for which no citation is given | + | 1. Jefferson, "[[Notes for the Biography of George Wythe]]", filed under August 31, 1820, Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress; Hayden, <u>[[Virginia Genealogies]]</u>, 382; Tyler, "[[Great American Lawyers|George Wythe]]", <u>loc. cit</u>., 82-83, is authority for the date, for which no citation is given |

2. McIlwaine, ed., <u>Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia</u>, IV, 369, 413. In November, 1936, the writer was told in Williamsburg that "Powhatan" is now owned by a Mr. E. M. Slauson. The writer noted in passing that the name Taliaferro is one of frequent occurrence in the mid-eighteenth century records of Caroline and Spotsylvania counties, but he did not determine the relationships of these families to that in James City County. | 2. McIlwaine, ed., <u>Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia</u>, IV, 369, 413. In November, 1936, the writer was told in Williamsburg that "Powhatan" is now owned by a Mr. E. M. Slauson. The writer noted in passing that the name Taliaferro is one of frequent occurrence in the mid-eighteenth century records of Caroline and Spotsylvania counties, but he did not determine the relationships of these families to that in James City County. | ||

| Line 1,577: | Line 1,581: | ||

===Page 81=== | ===Page 81=== | ||

| − | home during the campaign. One of these explained that Wager "had assisted him in his Distress, and therefore he did treat the Freeholders at that Time", adding his intention to do the same thing "as often as M<sup>r</sup> <u>Wager</u> and M<sup>r</sup> <u>Wythe</u>, should be candidates for that County." The Committee learned, too, that at a meeting of freeholders "procured by M<sup>r</sup> <u>Wythe</u> who was a Candidate or his Friends" some of his backers promised that Wythe would serve as burgess without compensation and "that they would give Bond to repay any Thing that should be levied on the County for him...." Not to be outdone, Wager had offered to match these terms, which gave an unheralded wag by the name of Cary his cue to declare, "now we have got two men that will serve us for nothing, which he was glad of, as he found it very difficult to pay his Taxes...."<sup>1</sup> But, since Cary had not voted for Wager, the Committee could find nothing illegal in Wager's campaign practises. Accordingly, the result of the disputed election hinged upon the qualifications of the voters. The Committee found that seven of Wager's supporters were not freeholders and ruled out only three of Tabb's votes. By these subtractions Tabb was seated by a plurality of one over Wager, who had originally polled a three-vote lead.<sup>2</sup> | + | home during the campaign. One of these explained that Wager "had assisted him in his Distress, and therefore he did treat the Freeholders at that Time", adding his intention to do the same thing "as often as M<sup>r</sup> <u>Wager</u> and [[George Wythe|M<sup>r</sup> <u>Wythe</u>]], should be candidates for that County." The Committee learned, too, that at a meeting of freeholders "procured by M<sup>r</sup> <u>Wythe</u> who was a Candidate or his Friends" some of his backers promised that Wythe would serve as burgess without compensation and "that they would give Bond to repay any Thing that should be levied on the County for him...." Not to be outdone, Wager had offered to match these terms, which gave an unheralded wag by the name of Cary his cue to declare, "now we have got two men that will serve us for nothing, which he was glad of, as he found it very difficult to pay his Taxes...."<sup>1</sup> But, since Cary had not voted for Wager, the Committee could find nothing illegal in Wager's campaign practises. Accordingly, the result of the disputed election hinged upon the qualifications of the voters. The Committee found that seven of Wager's supporters were not freeholders and ruled out only three of Tabb's votes. By these subtractions Tabb was seated by a plurality of one over Wager, who had originally polled a three-vote lead.<sup>2</sup> |

---- | ---- | ||

| Line 1,586: | Line 1,590: | ||

===Page 82=== | ===Page 82=== | ||

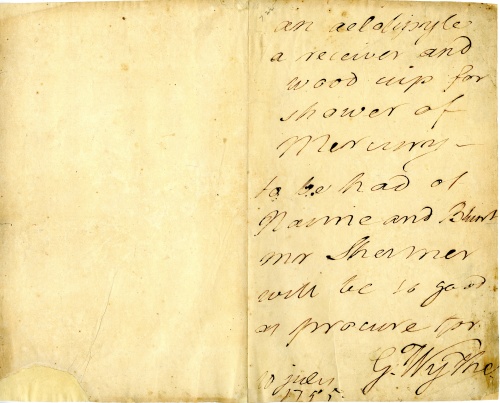

| − | Defeated in this somewhat typical campaign, George Wythe watched for two years from the outside the sessions of the Burgesses elected in 1756. That, as has been previously intimated, was the only House between 1748 and the Revolution with which he had no official connection. | + | [[File:WytheNaimeAndBlunt10July1755.jpg|thumb|500px|Wythe's order for scientific equipment, dated July 10, 1755. Original in the [http://library.haverford.edu/file-id-1037 Charles Roberts Autograph Letters Collection,] [http://library.haverford.edu/places/special-collections/ Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College,] Haverford, Pennsylvania.]] |

| + | Defeated in this somewhat typical campaign, [[George Wythe]] watched for two years from the outside the sessions of the [[wikipedia:House of Burgesses|Burgesses]] elected in 1756. That, as has been previously intimated, was the only House between 1748 and the [[wikipedia:American Revolution|Revolution]] with which he had no official connection. | ||

The earliest available writing from Wythe's pen now known to be extant constitutes a signed order for certain merchandize, but exactly what the articles he desired were is a matter of conjecture: "an aelolipyle a receiver and wood cup for shower of Mercury to be had of Naime and Blunt mr Shermer will be so good as [to] procure for G. Wythe."<sup>1</sup> | The earliest available writing from Wythe's pen now known to be extant constitutes a signed order for certain merchandize, but exactly what the articles he desired were is a matter of conjecture: "an aelolipyle a receiver and wood cup for shower of Mercury to be had of Naime and Blunt mr Shermer will be so good as [to] procure for G. Wythe."<sup>1</sup> | ||

| Line 1,595: | Line 1,600: | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| − | The activities and attainments of the third decade in George Wythe's life have thus been reconstructed as fully as authentic sources permit. To complete this review of those years only one consideration remains. An uncomplimentary legend, base in its implications, cannot be ignored. | + | The activities and attainments of the third decade in [[George Wythe|George Wythe's]] life have thus been reconstructed as fully as authentic sources permit. To complete this review of those years only one consideration remains. An uncomplimentary legend, base in its implications, cannot be ignored. |

Certain fictional reports have portrayed the Wythe of this period as a "wild and thoughtless youth" who yielded to the "seductions of pleasure" for nine or ten years, during which his career consisted of "dissipation and intemperance". This tradition was first promulgated obscurely in the year after his death<sup>2</sup> and was popularized and spread abroad for | Certain fictional reports have portrayed the Wythe of this period as a "wild and thoughtless youth" who yielded to the "seductions of pleasure" for nine or ten years, during which his career consisted of "dissipation and intemperance". This tradition was first promulgated obscurely in the year after his death<sup>2</sup> and was popularized and spread abroad for | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| − | 1. Ms. of George Wythe, July 10, 1755, Roberts Autograph Collection, Haverford College Library. | + | 1. [[Wythe to Shermer, 10 July 1755|Ms. of George Wythe, July 10, 1755]], [http://library.haverford.edu/file-id-1037 Roberts Autograph Collection,] [http://library.haverford.edu/places/special-collections/ Haverford College Library.] |

2. "[[Memoirs of the Late George Wythe, Esquire]]", <u>The American Gleaner, and Virginia Magazine</u>, I (1807), 1-2. This account is openly didactic. | 2. "[[Memoirs of the Late George Wythe, Esquire]]", <u>The American Gleaner, and Virginia Magazine</u>, I (1807), 1-2. This account is openly didactic. | ||

| Line 1,608: | Line 1,613: | ||

years by certain biographers of "Grub Street" caliber or less.<sup>1</sup> Significantly, no memoirs written by persons known to have been intimately acquainted with the man suggest any such traits in his character.<sup>2</sup> A full century had passed before enough thought was focussed on the theory to bring forth an | years by certain biographers of "Grub Street" caliber or less.<sup>1</sup> Significantly, no memoirs written by persons known to have been intimately acquainted with the man suggest any such traits in his character.<sup>2</sup> A full century had passed before enough thought was focussed on the theory to bring forth an | ||

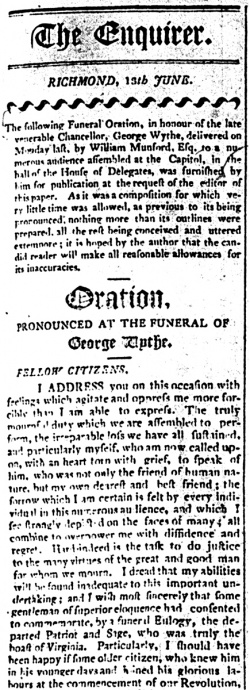

| + | [[File:RichmondEnquirer13June1806P3Detail.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Detail from page three of the Richmond ''Enquirer'' for June 13, 1806, with William Munford's [[Oration, Pronounced at the Funeral of George Wythe|funeral oration for George Wythe]].]] | ||

---- | ---- | ||

1. An extremely slavish paraphrase of the 1807 "[[Memoirs of the Late George Wythe, Esquire|Memoirs]]" adopted the account almost verbatim: "[[Media:HallAmericanLawJournal1810.pdf|George Wythe]]", <u>American Law Journal</u>, III (1810), 93. Thence the idea was transmitted to [Smith,] "[[Biography of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence|George Wythe]]", <u>loc. cit</u>., 173. Three later condensations of Smith's sketch, each of which sacrificed disproportionately other information in preference to omitting the moral of Wythe's youthful aberrations, adopted the fable: Charles A. Goodrich, "George Wythe", in his<u> Lives of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence</u>, 365; N. Dwight, "George Wythe", in his <u>The Lives of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence</u>, 267; B. J. Lossing, "George Wythe", in his <u>Biographical Sketches of the Signers of the Declaration of American Independence</u>, 163. Like that cited in the preceding footnote, all of these sources use the fable because of its possibilities as an instructive example. Indication of the widespread credence which unauthoritative tales of this kind may sometimes gain is given in the fact that this legend is solemnly reported as unquestioned truth in the article on Wythe in the large French biographical dictionary, <u>[[Biographie Universelle]]</u>. | 1. An extremely slavish paraphrase of the 1807 "[[Memoirs of the Late George Wythe, Esquire|Memoirs]]" adopted the account almost verbatim: "[[Media:HallAmericanLawJournal1810.pdf|George Wythe]]", <u>American Law Journal</u>, III (1810), 93. Thence the idea was transmitted to [Smith,] "[[Biography of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence|George Wythe]]", <u>loc. cit</u>., 173. Three later condensations of Smith's sketch, each of which sacrificed disproportionately other information in preference to omitting the moral of Wythe's youthful aberrations, adopted the fable: Charles A. Goodrich, "George Wythe", in his<u> Lives of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence</u>, 365; N. Dwight, "George Wythe", in his <u>The Lives of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence</u>, 267; B. J. Lossing, "George Wythe", in his <u>Biographical Sketches of the Signers of the Declaration of American Independence</u>, 163. Like that cited in the preceding footnote, all of these sources use the fable because of its possibilities as an instructive example. Indication of the widespread credence which unauthoritative tales of this kind may sometimes gain is given in the fact that this legend is solemnly reported as unquestioned truth in the article on Wythe in the large French biographical dictionary, <u>[[Biographie Universelle]]</u>. | ||

| Line 1,617: | Line 1,623: | ||

outright doubt,<sup>1</sup> and it is only in the last decade that distinct denials have been made.<sup>2</sup> | outright doubt,<sup>1</sup> and it is only in the last decade that distinct denials have been made.<sup>2</sup> | ||

| − | These recent defenders of Wythe's personal conduct have pointed out the probability that his distinctions in the House of Burgesses, success in the county courts, and appointment as Attorney General could not have come to a conspicuous degenerate or to any one of the greater-than-average self-indulgence — and that is in itself convincing testimony against the allegation. But its details alone are inaccurate enough to puncture this fabricated story, which supplies a motive by stating that an orphaned George came by inheritance on his twenty-first birthday into the unprotected control of a sizable fortune, that he squandered it in a prodigal fashion. Indubitable refutation of such assumptions has been given within this chapter in the fact that George Wythe became his father's heir, by the intestate death of his older brother, only when he was approaching the age of thirty. Wythe never possessed enough wealth to have suffered its enervating influence. | + | These recent defenders of Wythe's personal conduct have pointed out the probability that his distinctions in the [[wikipedia:House of Burgesses|House of Burgesses]], success in the county courts, and appointment as [[wikipedia:List of Attorneys General of Virginia|Attorney General]] could not have come to a conspicuous degenerate or to any one of the greater-than-average self-indulgence — and that is in itself convincing testimony against the allegation. But its details alone are inaccurate enough to puncture this fabricated story, which supplies a motive by stating that an orphaned George came by inheritance on his twenty-first birthday into the unprotected control of a sizable fortune, that he squandered it in a prodigal fashion. Indubitable refutation of such assumptions has been given within this chapter in the fact that [[George Wythe]] became his father's heir, by the intestate death of his older brother, only when he was approaching the age of thirty. Wythe never possessed enough wealth to have suffered its enervating influence. |

Had the legend of misspent years had any other origin than its true one, it might be a malicious slander, significant in any delineation of Wythe's character merely because some calumniator had taken the trouble to defame his reputation with a deliberate libel or aspersion. Yet no such | Had the legend of misspent years had any other origin than its true one, it might be a malicious slander, significant in any delineation of Wythe's character merely because some calumniator had taken the trouble to defame his reputation with a deliberate libel or aspersion. Yet no such | ||

| Line 1,637: | Line 1,643: | ||

===Page 86=== | ===Page 86=== | ||

| − | positive that Wythe lived moderately, observing faithfully the rules of contemporary conventions and the dictates of his own conscience. One of his friends admitted, about six years after his death, that he had had a "natural" tendency to "instability" but recalled that it had been held in check "with a tight rein".<sup>1</sup> Others spoke of his "truly laudable" conduct in a "private life ... spent in the practice of social virtues, and in the enjoyment of much domestic felicity ...",<sup>2</sup> described his virtue as "of the purest tint", and attributed his "general good health" to "temperance and regularity in all his habits."<sup>3</sup> To one of the very biographers who contributed to the spread of the falsehood of Wythe's alleged dissipation Thomas Jefferson had given, together with some information designed to serve as "landmarks to distinguish truth from error, in what you hear from others", assurance that "the exalted virtue of the man will also be a polar star to guide you in all matters which may touch that element of his character", adding on second thought, "but on that you will receive [<u>sic</u>] imputations from no man; for, as far as I know, he never had an enemy."<sup>4</sup> | + | positive that Wythe lived moderately, observing faithfully the rules of contemporary conventions and the dictates of his own conscience. One of his friends admitted, about six years after his death, that he had had a "natural" tendency to "instability" but recalled that it had been held in check "with a tight rein".<sup>1</sup> Others spoke of his "truly laudable" conduct in a "private life ... spent in the practice of social virtues, and in the enjoyment of much domestic felicity ...",<sup>2</sup> described his virtue as "of the purest tint", and attributed his "general good health" to "temperance and regularity in all his habits."<sup>3</sup> To one of the very biographers who contributed to the spread of the falsehood of Wythe's alleged dissipation [[wikipedia:Thomas Jefferson|Thomas Jefferson]] had given, together with some information designed to serve as "landmarks to distinguish truth from error, in what you hear from others", assurance that "the exalted virtue of the man will also be a polar star to guide you in all matters which may touch that element of his character", adding on second thought, "but on that you will receive [<u>sic</u>] imputations from no man; for, as far as I know, he never had an enemy."<sup>4</sup> |

---- | ---- | ||

| Line 1,650: | Line 1,656: | ||

===Page 87=== | ===Page 87=== | ||

| − | It has been shown by his own admission that George Wythe neglected during his third decade some opportunities for the improvement of his scanty education. Of this fault he was never again guilty. Demands of public or private business made incessant inroads upon his time, but nothing could prevent the penetrating study of a man who developed, after his professional career had been established, the genuine love of learning for its own sake which is so essential a foundation for scholarship. The loss of hours spent less beneficially was redeemed a hundred fold within the next fifty years.<sup>1</sup> Indefatigable in his application, he became noted for a solidity and penetration which none of his contemporaries surpassed. Breadth of interest, too, characterized his self-education. In his later years he was respectfully dubbed "the walking library".<sup>2</sup> And when he died someone reflected that "there was no art or profession of which he had not a correct idea."<sup>3</sup> | + | It has been shown by his own admission that [[George Wythe]] neglected during his third decade some opportunities for the improvement of his scanty education. Of this fault he was never again guilty. Demands of public or private business made incessant inroads upon his time, but nothing could prevent the penetrating study of a man who developed, after his professional career had been established, the genuine love of learning for its own sake which is so essential a foundation for scholarship. The loss of hours spent less beneficially was redeemed a hundred fold within the next fifty years.<sup>1</sup> Indefatigable in his application, he became noted for a solidity and penetration which none of his contemporaries surpassed. Breadth of interest, too, characterized his self-education. In his later years he was respectfully dubbed "the walking library".<sup>2</sup> And when he died someone reflected that "there was no art or profession of which he had not a correct idea."<sup>3</sup> |

First among the fields of knowledge to which Wythe turned his attention was the treasury of classical literature. Therein lay throughout a long lifetime his chief intellectual interest, and until he was about fifty years of age his unremitting diligence in self-instruction was concentrated | First among the fields of knowledge to which Wythe turned his attention was the treasury of classical literature. Therein lay throughout a long lifetime his chief intellectual interest, and until he was about fifty years of age his unremitting diligence in self-instruction was concentrated | ||

| Line 1,659: | Line 1,665: | ||

2. Anonymous "[[Richmond Enquirer, 10 June 1806|Communication]]", <u>The Enquirer</u>, June 10, 1806. | 2. Anonymous "[[Richmond Enquirer, 10 June 1806|Communication]]", <u>The Enquirer</u>, June 10, 1806. | ||

| − | 3. "[[Virginia Gazette, and General Advertiser, 18 June 1806|Communication]]" signed "A.B.", Virginia Gazette, and General Advertiser, June 18, 1806. | + | 3. "[[Virginia Gazette, and General Advertiser, 18 June 1806|Communication]]" signed "A.B.", <u>Virginia Gazette, and General Advertiser</u>, June 18, 1806. |

===Page 88=== | ===Page 88=== | ||

| − | primarily on the acquisition of facts and principles recorded by the writers of ancient Greece and Rome. The handicap of inadequate formal schooling and of only preliminary grammatical study at his mother's knee meant nothing to him, though they had together been barely sufficient to let him realize how unqualified for progress he was. On his own initiative and with no other tutor than himself, he plunged deeply into a discriminating absorption in the classics.<sup>1</sup> | + | primarily on the acquisition of facts and principles recorded by the [[wikipedia:Ancient Greek literature|writers of ancient Greece]] and [[wikipedia:Latin literature|Rome]]. The handicap of inadequate formal schooling and of only preliminary grammatical study at his mother's knee meant nothing to him, though they had together been barely sufficient to let him realize how unqualified for progress he was. On his own initiative and with no other tutor than himself, he plunged deeply into a discriminating absorption in the classics.<sup>1</sup> |

| − | Rather early in this study he procured a volume of blank pages, average in size, not unlike a typical eighteenth-century lawyer's commonplace book, in which he recorded minute notes of his personal [[Etymological Praxis|research in the etymology of Greek and Latin words]]. About 150 pages of his book, which has been preserved, contain his comparisons of Latin equivalents with the original Greek text of Homer's <u>Iliad</u> and with other Hellenic literature. No better monument to Wythe's patient burrowings in linguistics can be imagined than this private product of his explorations in the original meanings of words, | + | Rather early in this study he procured a volume of blank pages, average in size, not unlike a typical eighteenth-century lawyer's commonplace book, in which he recorded minute notes of his personal [[Etymological Praxis|research in the etymology of Greek and Latin words]]. About 150 pages of his book, which has been preserved, contain his comparisons of Latin equivalents with the original Greek text of [[wikipedia:Iliad|Homer's <u>Iliad</u>]] and with other Hellenic literature. No better monument to Wythe's patient burrowings in linguistics can be imagined than this private product of his explorations in the original meanings of words, |

---- | ---- | ||

| Line 1,674: | Line 1,680: | ||

which he certainly never intended for the eye of posterity.<sup>1</sup> By such labors he acquired a knowledge of the ancient languages which was "critically correct".<sup>2</sup> | which he certainly never intended for the eye of posterity.<sup>1</sup> By such labors he acquired a knowledge of the ancient languages which was "critically correct".<sup>2</sup> | ||

| − | Homer's immortal tale of the fall of Troy, however, was only a beginning. Wythe's mind ran the gamut of Greek and Latin poets, historians, and philosophers; with all of these whose writings he could obtain he became as familiar as he was with any English author, reading them with equal ease.<sup>3</sup> Thomas Jefferson spoke of him later without reservation as | + | Homer's immortal [[wikipedia:Iliad|tale]] of the fall of Troy, however, was only a beginning. Wythe's mind ran the gamut of Greek and Latin poets, historians, and philosophers; with all of these whose writings he could obtain he became as familiar as he was with any English author, reading them with equal ease.<sup>3</sup> Thomas Jefferson spoke of him later without reservation as |

---- | ---- | ||

| − | 1. [George Wythe, [[Etymological Praxis|An Etymological Praxis | + | 1. [[George Wythe]], [[Etymological Praxis|An Etymological Praxis]], Virginia Historical Society Library. This Ms. quarto volume has no title page and is undated; but Wythe's characteristic handwriting constitutes a positive means to identification. The writer is of the opinion, on the basis of penmanship comparisons with Wythe's letters, that it was definitely of a period before 1765. The last six of its unnumbered pages contain a copy of biographical sketches of John Holloway and William Hopkins, colonial Virginia lawyers who died in 1734, transcribed by some one other than Wythe from Sir John Randolph's "Breviate Book". A letter of transmittal to the Society is pasted to its front cover. "I herewith sent you, the book which I promised you for your Society. It was (as I informed you) the property of the late venerable and learned Chancellor Wythe, and I believe is altogether in his hand writing [<u>sic</u>], although the character of the copy from 'Sir John's Breviate Book' seems to be different from that of the Greek and Latin. Much of the largest portion of the book is a Clavis Όμηρου, or Etymological Praxis, on which several of the books of the Iliad, and some of the παχωίδία<ref>As Hemphill did not possess Greek characters on his typewriter, these characters were originally added to the [[Media:HemphillGeorgeWytheTheColonialBriton1937.pdf|dissertation]] in pen (18MB PDF).</ref> which will serve in a striking manner to illustrate the great industry of that distinguished man": [[John Page, Jr., to James E. Heath, 3 January 1834|John Page to James B. Heath, January 3, 1834]]. The existence of this Ms. has been previously commented upon only by Grigsby, [[Virginia Convention of 1776|<u>Virginia Convention of 1776</u>]], 120, who cited it as evidence that Wythe's accurate familiarity with Latin and Greek began in middle life. The two biographical sketches were reprinted in <u>The Virginia Historical Register</u>, I, 119-123. |

2. Anonymous "[[Richmond Enquirer, 10 June 1806|Communication]]", <u>The Enquirer</u>, June 10, 1806. | 2. Anonymous "[[Richmond Enquirer, 10 June 1806|Communication]]", <u>The Enquirer</u>, June 10, 1806. | ||

| Line 1,685: | Line 1,691: | ||

===Page 90=== | ===Page 90=== | ||

| − | "the best Latin and Greek scholar" in Virginia,<sup>1</sup> and a contemporary who was better qualified than Jefferson to pass judgment in literary matters asserted that his attainments in the classics had rarely been equaled in all the American colonies and states.<sup>2</sup> Or, as still another contemporary put it, he labored delightedly "not only through an apprenticeship, but almost through a life in the dead language."<sup>3</sup> A rather recent figure in the world of American letters boasted that he owned a rare [[Anacreontis Carmina cum Sapphonis, et Alcaei fragmentis|1757 edition of the odes to Anacreon, Sappho, and Alcaeus]], which had once been in the library of George Wythe.<sup>4</sup> If anything, he carried too far his love of ancient scholarship, which became increasingly as he grew older his pride as well as his joy. Conversation and correspondence he naturally enriched with quotations, but there is a limit at which the foible of classical quotation borders upon pedantry pure and simple. Any Wythe appears never to have hesitated to sprinkle even the most technical legal opinions and decisions with excerpts from his studies, to the utter consternation of less learned associates who could not | + | "the best Latin and Greek scholar" in Virginia,<sup>1</sup> and a contemporary who was better qualified than Jefferson to pass judgment in literary matters asserted that his attainments in the classics had rarely been equaled in all the American colonies and states.<sup>2</sup> Or, as still another contemporary put it, he labored delightedly "not only through an apprenticeship, but almost through a life in the dead language."<sup>3</sup> A rather recent figure in the world of American letters boasted that he owned a rare [[Anacreontis Carmina cum Sapphonis, et Alcaei fragmentis|1757 edition of the odes to Anacreon, Sappho, and Alcaeus]], which had once been in the library of [[George Wythe]].<sup>4</sup> If anything, he carried too far his love of ancient scholarship, which became increasingly as he grew older his pride as well as his joy. Conversation and correspondence he naturally enriched with quotations, but there is a limit at which the foible of classical quotation borders upon pedantry pure and simple. Any Wythe appears never to have hesitated to sprinkle even the most technical legal opinions and decisions with excerpts from his studies, to the utter consternation of less learned associates who could not |

---- | ---- | ||

| Line 1,730: | Line 1,736: | ||

===Page 93=== | ===Page 93=== | ||

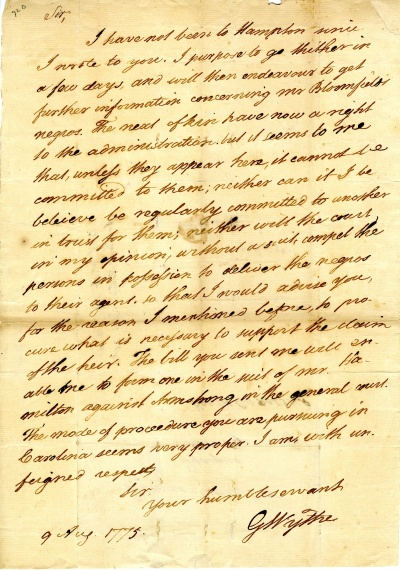

| + | [[File:Leney1807Wythe.jpg|thumb|left|300px|"George Wythe, Esq.," by William Satchwell Leney, engraved for the [[Memoirs of the Late George Wythe, Esquire|''American Gleaner and Virginia Magazine'']] 1. no. 1 (24 January 1807) 1-3. Original at the [http://vhs4.vahistorical.org/starweb/vhs/servlet.starweb?path=vhs/vhs.web Virginia Historical Society].]] | ||

between grey eyes as the most readily distinguishable item among his engagingly blended features. A complete absence of affection controlled courteous manners naturally urbane in both social and professional contacts.<sup>1</sup> | between grey eyes as the most readily distinguishable item among his engagingly blended features. A complete absence of affection controlled courteous manners naturally urbane in both social and professional contacts.<sup>1</sup> | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| − | 1. <u>Ibid</u>.; Cooke, "George Wythe", Manuscript Biographies Collection, Pennsylvania Historical Society Library. An excellent portrait in the lobby of the George Wythe Hotel, Wytheville, Virginia, pictures him at an earlier age than any other — apparently at about thirty-five. The [[George Wythe House|Wythe House]] in Williamsburg houses a handsome Turnbull [''sic''] semi-profile painting of a somewhat later date. A [[:File:Leney1807Wythe.jpg|full-profile by Longacre]], originally painted in the missing issues of <u>The American Gleaner, and Virginia Magazine</u>,<ref>The original portrait in the 1807 ''American Gleaner'' was created by [[:File:Leney1807Wythe.jpg|William Satchwell Leney]], not J.B. Longacre. Longacre's engraving is labeled as being based on "a Portrait in the American Gleaner," but was created for Sanderson's [[Biography of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence]], c. 1823.</ref> is definitely applicable only to Wythe's old age and is very widely available through engraved copies in publications and libraries. Mrs. Catherine Carter Critcher of Washington, D. C., a collateral descendant, presented to the Wythe House in 1927 an original oil painting done from the [[:File:LongacreWythe.jpg|Longacre model]]. In the Wythe House there is also a small circular profile, giving the impression of a semi-caricature, done by the famous elder Peale with the aid of an extinct "profilograph" invention. In Wythe's last years he became stooped and thin. | + | 1. <u>Ibid</u>.; Cooke, "George Wythe", Manuscript Biographies Collection, Pennsylvania Historical Society Library. An excellent portrait in the lobby of the George Wythe Hotel, Wytheville, Virginia, pictures him at an earlier age than any other — apparently at about thirty-five. The [[George Wythe House|Wythe House]] in Williamsburg houses a handsome Turnbull [''sic''] semi-profile painting of a somewhat later date. A [[:File:Leney1807Wythe.jpg|full-profile by Longacre]], originally painted in the missing issues of <u>The American Gleaner, and Virginia Magazine</u>,<ref>The original portrait in the 1807 ''American Gleaner'' was created by [[:File:Leney1807Wythe.jpg|William Satchwell Leney]], not J.B. Longacre. Longacre's engraving is labeled as being based on "a Portrait in the American Gleaner," but was created for Sanderson's [[Biography of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence]], c. 1823.</ref> is definitely applicable only to Wythe's old age and is very widely available through engraved copies in publications and libraries. Mrs. [[wikipedia:Catharine Carter Critcher|Catherine Carter Critcher]] [''sic''] of Washington, D. C., a collateral descendant, presented to the Wythe House in 1927 an original oil painting done from the [[:File:LongacreWythe.jpg|Longacre model]]. In the Wythe House there is also a small circular profile, giving the impression of a semi-caricature, done by the famous elder Peale with the aid of an extinct "profilograph" invention. In Wythe's last years he became stooped and thin. |

==Chapter IV== | ==Chapter IV== | ||

| Line 1,754: | Line 1,761: | ||

</center> | </center> | ||