Difference between revisions of "Book of Entries"

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

|pages=9, 713 leaves, [17] pages | |pages=9, 713 leaves, [17] pages | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Coke Sir Edward Coke] (1552–1634) was “the embodiment of common law.”<ref>''Encyclopædia Britannica Online'', s. v. "Sir Edward Coke," accessed October 09, 2013, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/124844/Sir-Edward-Coke.</ref> He enrolled in [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clifford%27s_Inn Clifford's Inn] in 1571, transferred to the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inner_Temple Inner Temple] in 1572, and was called to the bar in 1578.<ref>Allen D. Boyer, [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/5826 "Coke, Sir Edward (1552–1634)"] in ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed Oct. 3, 2013 | + | [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Coke Sir Edward Coke] (1552–1634) was “the embodiment of common law.”<ref>''Encyclopædia Britannica Online'', s. v. "Sir Edward Coke," accessed October 09, 2013, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/124844/Sir-Edward-Coke.</ref> He enrolled in [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clifford%27s_Inn Clifford's Inn] in 1571, transferred to the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inner_Temple Inner Temple] in 1572, and was called to the bar in 1578.<ref>Allen D. Boyer, [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/5826 "Coke, Sir Edward (1552–1634)"] in ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed Oct. 3, 2013.</ref> One of the most prominent English lawyers in the 1580s and 1590s, he became solicitor-general in 1592<ref>Allen D. Boyer, ''Sir Edward Coke and the Elizabethan Age'' (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003), 216.</ref> and attorney-general in 1594. In 1606, after being created serjeant-at-law, Coke was appointed chief justice of the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Court_of_Common_Pleas_%28England%29 Court of Common Pleas]. He was transferred, against his will, to chief justice of the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Court_of_King%27s_Bench_%28England%29 Court of King's Bench]in 1613; he also became a member of the privy council and was named lord chief justice of England, the first person to be granted that title.<ref>''Encyclopædia Britannica Online'', s. v. "Sir Edward Coke."</ref> Even while sitting at the King’s Bench, Coke asserted common law’s supremacy over all persons and institutions except Parliament.<ref>Ibid."</ref> After several political and judicial skirmishes with James I and Francis Bacon, Coke was suspended from the privy council and removed from the bench in 1616.<ref>Ibid.</ref> While he never returned to the bench, Coke did return to Parliament and was elected to that body four times from 1620 to 1629. During this time, he took a pivotal lead in creating and composing the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petition_of_Right Petition of Right]. "This document cited the Magna Carta and reminded Charles I that the law gave Englishmen their rights, not the king ... Coke’s petition focused on ... due process, protection from unjust seizure of property or imprisonment, the right to trial by jury of fellow Englishmen, and protection from unjust punishments or excessive fines."<ref>''Bill of Rights Institute'' website, s.v. "Petition of Right (1628)", accessed Oct. 3, 2013 http://billofrightsinstitute.org/resources/educator-resources/americapedia/americapedia-documents/petition-of-right/.</ref> After this triumph, Coke spent his remaining years at his home, Stoke Poges, working on ''The Institutes of the Laws of England'', another endeavor for which he is rightly famous.<ref>Boyer, "Coke, Sir Edward."</ref><br /> |

<br /> | <br /> | ||

His ''Book of Entries'' is a massive collection of pleadings intended to guide other lawyers through England’s courts.<ref>Boyer, "Coke, Sir Edward."</ref> Published in law French, the volume to some degree supplements Coke's ''Reports'' because it contained the entire record of many cases in the latter set.<ref>J. G. Marvin, ''Legal Bibliography or a Thesaurus of American, English, Irish, and Scotch Law Books'' (Philadelphia: T. & J. W. Johnson, Law Booksellers, 1847), 212.</ref> As a reliable legal authority, Coke's ''Book of Entries'' was regarded so highly that it could "certainly claim the first place."<ref>Ibid.</ref> | His ''Book of Entries'' is a massive collection of pleadings intended to guide other lawyers through England’s courts.<ref>Boyer, "Coke, Sir Edward."</ref> Published in law French, the volume to some degree supplements Coke's ''Reports'' because it contained the entire record of many cases in the latter set.<ref>J. G. Marvin, ''Legal Bibliography or a Thesaurus of American, English, Irish, and Scotch Law Books'' (Philadelphia: T. & J. W. Johnson, Law Booksellers, 1847), 212.</ref> As a reliable legal authority, Coke's ''Book of Entries'' was regarded so highly that it could "certainly claim the first place."<ref>Ibid.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 00:04, 3 March 2014

by Sir Edward Coke

| A Book of Entries | |

|

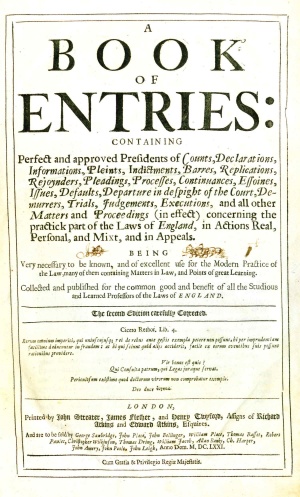

Title page from A Book of Entries, George Wythe Collection, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary. | |

| Author | Sir Edward Coke |

| Published | London: Printed by John Streater, James Flesher, and Henry Twyford, assigns of Richard Atkins and Edward Atkins |

| Date | 1671 |

| Edition | Second, carefully corrected |

| Language | English |

| Volumes | 1 volume set |

| Pages | 9, 713 leaves, [17] pages |

Sir Edward Coke (1552–1634) was “the embodiment of common law.”[1] He enrolled in Clifford's Inn in 1571, transferred to the Inner Temple in 1572, and was called to the bar in 1578.[2] One of the most prominent English lawyers in the 1580s and 1590s, he became solicitor-general in 1592[3] and attorney-general in 1594. In 1606, after being created serjeant-at-law, Coke was appointed chief justice of the Court of Common Pleas. He was transferred, against his will, to chief justice of the Court of King's Benchin 1613; he also became a member of the privy council and was named lord chief justice of England, the first person to be granted that title.[4] Even while sitting at the King’s Bench, Coke asserted common law’s supremacy over all persons and institutions except Parliament.[5] After several political and judicial skirmishes with James I and Francis Bacon, Coke was suspended from the privy council and removed from the bench in 1616.[6] While he never returned to the bench, Coke did return to Parliament and was elected to that body four times from 1620 to 1629. During this time, he took a pivotal lead in creating and composing the Petition of Right. "This document cited the Magna Carta and reminded Charles I that the law gave Englishmen their rights, not the king ... Coke’s petition focused on ... due process, protection from unjust seizure of property or imprisonment, the right to trial by jury of fellow Englishmen, and protection from unjust punishments or excessive fines."[7] After this triumph, Coke spent his remaining years at his home, Stoke Poges, working on The Institutes of the Laws of England, another endeavor for which he is rightly famous.[8]

His Book of Entries is a massive collection of pleadings intended to guide other lawyers through England’s courts.[9] Published in law French, the volume to some degree supplements Coke's Reports because it contained the entire record of many cases in the latter set.[10] As a reliable legal authority, Coke's Book of Entries was regarded so highly that it could "certainly claim the first place."[11]

Evidence for Inclusion in Wythe's Library

Both Dean's Memo[12] and the Brown Bibliography[13] suggest Wythe owned the second edition of this title based on notes in John Marshall's commonplace book.[14]

Description of the Wolf Law Library's copy

View this book in William & Mary's online catalog.

References

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. "Sir Edward Coke," accessed October 09, 2013, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/124844/Sir-Edward-Coke.

- ↑ Allen D. Boyer, "Coke, Sir Edward (1552–1634)" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004- ), accessed Oct. 3, 2013.

- ↑ Allen D. Boyer, Sir Edward Coke and the Elizabethan Age (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003), 216.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. "Sir Edward Coke."

- ↑ Ibid."

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Bill of Rights Institute website, s.v. "Petition of Right (1628)", accessed Oct. 3, 2013 http://billofrightsinstitute.org/resources/educator-resources/americapedia/americapedia-documents/petition-of-right/.

- ↑ Boyer, "Coke, Sir Edward."

- ↑ Boyer, "Coke, Sir Edward."

- ↑ J. G. Marvin, Legal Bibliography or a Thesaurus of American, English, Irish, and Scotch Law Books (Philadelphia: T. & J. W. Johnson, Law Booksellers, 1847), 212.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Memorandum from Barbara C. Dean, Colonial Williamsburg Found., to Mrs. Stiverson, Colonial Williamsburg Found. (June 16, 1975), 10 (on file at Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary).

- ↑ Bennie Brown, "The Library of George Wythe of Williamsburg and Richmond," (unpublished manuscript, May, 2012) Microsoft Word file. Earlier edition available at: https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/13433

- ↑ The Papers of John Marshall, eds. Herbert A. Johnson, Charles T. Cullen, and Nancy G. Harris (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, in association with the Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1974), 1:50.